Human rights campaigner Carmel Budiardjo died aged 96 on 10 July 2021, after a long and dynamic life of activism dating back to her years as a student activist in the 1940s

Human rights campaigner Carmel Budiardjo died aged 96 on 10 July 2021, after a long and dynamic life of activism dating back to her years as a student activist in the 1940s

Katharine McGregor

The author interviewed Carmel for a research project examining transnational activism in support of victims of the 1965 violence in Indonesia, for which she was an important voice. This obituary is based on a condensed version of her paper ‘The Making of a Transnational Activist: The Indonesian Human Rights Campaigner Carmel Budiardjo’ in The Transnational Activist: Transformations and Comparisons from the Anglo World since the Nineteenth Century, edited by Stefan Edberg and Sean Scalmer (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). It focuses on Carmel's sympathy for Indonesia and her activism for survivors of the 1965 violence. It is hoped that by sharing this information on her life it will help increase understanding of Carmel's commitment to Indonesia and human rights.

Carmel Budiardjo was born in 1925 in London to Jewish parents of Polish/ Russian background who had migrated to Britain as children. Her later years in high school overlapped with the outbreak of the Second World War. Her family experienced war close up during the bombing campaigns from September 1940 onwards. Anti-Semitism in Britain escalated during the war. At the same time her family became increasingly aware of the persecution of Jews by the Nazis in continental Europe. It is likely that her Jewish background and life experiences made her sensitive to the persecution of minorities.

In 1942, Carmel began a university degree majoring in sociology and economics at the London School of Economics (LSE). During her university years, Carmel became active in the British National Union of Students (NUS). Working in the international department of the Union gave Carmel further exposure to students from diverse countries. Carmel helped to organise the World Students’ Congress in Prague in August 1946, the same year that she graduated from the LSE. The focus of the Congress was on identifying causes that they believed students should support in the post-war world. It was decided that their mission would include the continuing struggles against fascism and oppression, contributing to relief work in war-damaged countries and promoting peace, security and democratisation worldwide. This included recognition of ongoing colonialism.

Following the Prague Congress and under the auspices of the newly founded International Union of Students (IUS), Carmel travelled to Yugoslavia as part of an international youth brigade. The group set out to help build the so-called Yugoslav Youth Railway, a 150-mile railway line that would provide a transport link from Bosnia to Slavonia. Students from twenty countries including Indonesia joined this project excavating tunnels along the mountainside and laying tracks. In my interviews with her Carmel spoke fondly of the intense camaraderie and her growing fascination with Indonesia during this trip.

In 1948, Carmel met her future husband, Budiardjo, in Prague at the offices of the IUS. Budiardjo was studying political science as one of a small cohort of elite Indonesian students studying abroad. They married in 1950 and she moved to Indonesia in 1951.

Life in Indonesia: from politics to prison

Upon her arrival in Indonesia Carmel experienced culture shock, with the extremes between the rich and poor especially confronting. Thrown into this new context, Carmel picked up Indonesian fairly quickly and began working as a translator for Antara news agency. She then got a job as a researcher in international economic relations for the Foreign Ministry. She lectured at Padjadjaran State University in Bandung and then at Respublika University in Jakarta, which was run by the Chinese political organisation Baperki. Determined to make a contribution to Indonesia, Carmel frequently wrote commentary in newspapers about the Indonesian economy , which was facing increasing pressures in the early 1960s, including severe inflation and a large balance of payments deficit.

As a university graduate and a lecturer, Carmel joined the Indonesian Graduates’ Association (Himpunan Sarjana Indonesia, HSI). In this capacity she was a vocal critic of Indonesia’s acceptance of International Monetary Fund (IMF) economic stabilisation policies in return for economic aid. She opposed free market economics and the lifting of price controls on basic commodities. HSI members carried out research into issues such as land ownership and how this might improve the position of Indonesian peasants.

From the late 1950s till the mid-1960s, there was fierce competition to increase membership of all Indonesian political parties. The Indonesian Communist Party (Partai Komunis Indonesia, PKI) rose in popularity during this period, reaching a membership of 3.5 million people by 1965 and a further 23.5 million in affiliated organisations. Carmel had both direct and indirect connections to the PKI. The first was through Baperki, the sponsor of the university where she lectured was on the political left, although it was not directly aligned with the PKI. Her second connection with through the HIS , which was aligned with the PKI. Carmel described the HSI as functioning like a party cell providing feedback on the direction of the party. Further to this, Carmel occasionally did translations for the PKI and she was in contact with some party leaders.

By 1965 Carmel considered Indonesia her home, but on the night of September 30, that year everything changed dramatically. That evening an armed group calling itself the September 30th Movement kidnapped and killed six high-ranking army generals and a lieutenant in Jakarta. The army quickly suppressed the movement and mounted a propaganda campaign linking it to the PKI. The army then carried out a brutal repression, killing approximately 500,000 people between 1965 and 1968, and overseeing mass detentions.

In the days following the Movement, Carmel grew increasingly afraid as stories trickled in from friends about arrests and houses being ransacked. Carmel lost her job at the Foreign Ministry and at university. Almost overnight, the army declared people affiliated with the communist party or aligned organisations to be dangerous. Between 1965 and 1968, Carmel’s husband, Budiardjo, who had been working as Assistant Minister at the Ministry of Sea Communications was twice arrested only to be released each time. Finally, on 3 September 1968, they they were both arrested, leaving two children aged 17 years and 12 years at home with her in-laws.

Carmel was held in miserable conditions with inadequate food, no bedding and no extra clothing. The last place of detention she was held was a women’s goal called Bukit Duri, translated in English as Thorn Hill.

In 1971, Amnesty International eventually secured Carmel’s release by successfully arguing for a reinstatement of Carmel’s British citizenship on the basis that she was stateless. This provided the grounds for her release. Her husband, however, remained in detention. She was determined to use her new freedom to campaign for the release of her fellow prisoners with whom she had shared experiences of joint political activism and imprisonment.

Founding TAPOL

By the time of Carmel’s release in the early 1970s, there were fairly limited international sources of support for the hundreds of thousands of Indonesian political prisoners languishing in prisons, detention centres and penal colonies in remote locations in Indonesia. Globally, the issue of Indonesian political prisoners failed to attract a lot of sympathy in the Western world, most likely because the prisoners were viewed as dangerous communists at a time when the war in Vietnam was underway and the Cold War was at its peak.

Upon arriving in London, Carmel used the connections she had in Amnesty and almost immediately set to work to help the prisoners she left behind. She felt compelled to act in response to the Indonesian repression. She wrote an extensive report for Amnesty on the conditions in Indonesian prisons and cases of torture and the names, stories and locations of prisoners she had met in detention. This led to Amnesty adopting some of women prisoners as cases in their campaign.

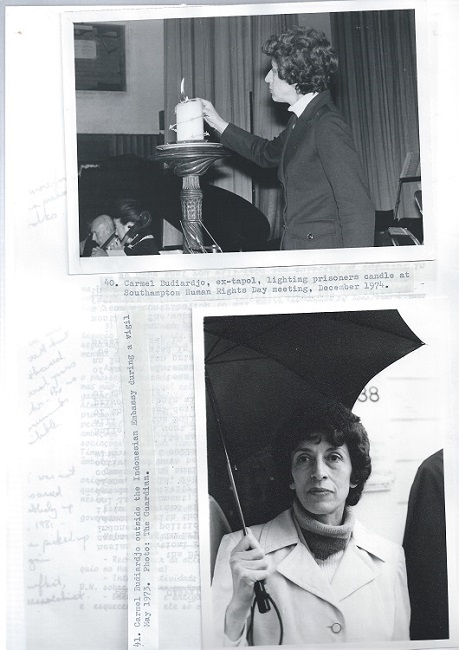

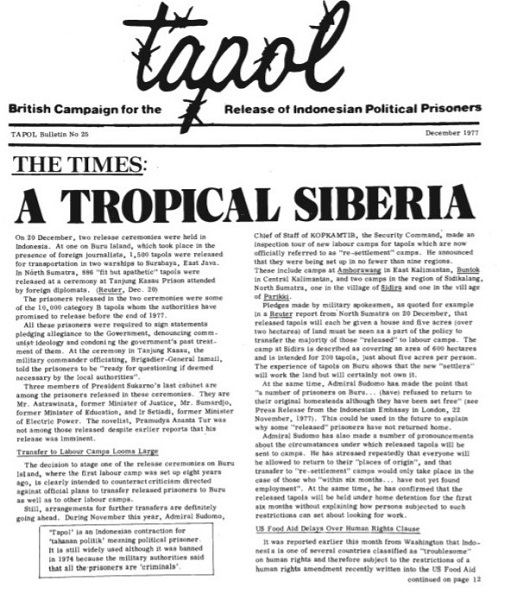

However, despite increasing Western critiques of torture and the infringement of civil liberties, which was largely Amnesty’s focus, Carmel did not believe that the Indonesian case was getting enough attention. In May 1973, Carmel established TAPOL, which she launched with a candlelight vigil held outside the Indonesian Embassy in London. The first derivation of the organisation’s name was TAPOL: The British Campaign for the Release of Indonesian Political Prisoners. Her primary motivation for activism was to secure the release of her husband and other Indonesian prisoners whom she had met in prison. TAPOL primarily emphasised ‘forgotten prisoners’ and the right to a fair trial as enshrined in principle 10 of the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights (UNDHR).

To keep the forgotten prisoners in focus, TAPOL used strategic locations and aligned their protest actions with key dates on the Indonesian national calendar. In 1973, TAPOL organised three vigils outside the Indonesian embassy in Britain at key moments, including the 17 August Independence Day celebration, and in the lead-up to and during, Inter-Governmental Group of Indonesia (IGGI) meetings, where donor nations and the World Bank met to discuss aid to Indonesia. At these protests they held up small placards with the face of an unknown Indonesian prisoner behind bars, together with other placards condemning the on-going imprisonments.

TAPOL disseminated information on the Indonesian repression through its English language bulletins. The bulletins provided updates on conditions in specific prisons and penal camps. They featured details of particular prisoners’ circumstances, called ‘case notes’. TAPOL attempted to use these short profiles of prisoners to connect readers of the bulletin with specific prisoners.

At one stage the TAPOL bulletin had 900 subscriptions and was also sold in several bookshops throughout the world. It was distributed across 75 countries in Europe, America, the Pacific and Australia and also had some subscribers in Indonesia. The Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation (Lembaga Bantuan Hukum, LBH), one of the few organisations in Indonesia able to advocate for prisoners, subscribed to the bulletin and distributed copies to other NGOs. In the repressive context of the Suharto regime (1966-1998) human rights activists and students who took an interest were able to read the bulletins at the offices of LBH and other NGOs.

TAPOL also used speaking tours to rally support. Carmel was one of the few former political prisoners to be released early, who had with access to the resources to publicise her experiences, and those of her fellow prisoners, to the world. In 1974, for example, Carmel toured Australia and New Zealand for five weeks to raise awareness about Indonesia’s prisoners. She spoke to politicians, academics and trade union activists. Carmel used her personal experiences of imprisonment to try to persuade more people to do something about Indonesian political prisoners. Through this advocacy, Carmel used the networks she could access to increase pressure on the Indonesian government to release the political prisoners.

When the Indonesian invasion of East Timor took place in 1975, TAPOL also took up this cause and changed its name to TAPOL: The Indonesia Human Rights Campaign to reflect a broader mandate.

In 1978, as a result of pressure from advocacy groups including TAPOL, the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), Amnesty, together with a new emphasis on human rights from the USA’s Carter Administration, the Indonesian government released the majority of political prisoners from 1965. The culmination of domestic pressure in donor countries had moved Western governments to press the issue. Here, the role of TAPOL along with other organisations, academics and journalists, was crucial in shaping domestic opinion by continuously reminding the public of the plight of those in prison.

Not all 1965 prisoners were, however, released at this time. TAPOL persisted in its advocacy for these cases and continued to report that former prisoners and their families were subjected to ongoing discrimination. TAPOL also highlighted the renewed ideological campaigns in Indonesia against the so-called communist threat. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s TAPOL continued to advocate on behalf of Indonesian political prisoners from Acehnese, East Timorese, West Papuan and Muslim political prisoners. Carmel remained informed and active in TAPOL until her recent passing.

Carmel’s legacy, carried on in the work of TAPOL today, is an enduring spotlight on human rights violations in Indonesia and compassion for political prisoners who have often been neglected by the outside world.

Kate McGregor (k.mcgregor@unimelb.edu.au) is an historian of Indonesia based in the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies at the University of Melbourne.

II Editor: Carmel Budiardjo was a good friend and regular contributor to Inside Indonesia over many decades, writing on human rights abuses and the plight of political prisoners in Papua and Aceh. Indicative of her decades-long support for other scholars and writers working on these themes, as recently as 2010 Carmel contributed this review of a book about Papuan women and in 1984, one of the earliest English translations of the writing of fellow political prisoner, Hersri Setiawan. Vale Carmel!