Mixed messaging from government about COVID-19 has left rumours and competing narratives to fill the information void, fuelling mistrust

Najmah, Sari Andajani, Kusnan, Sharyn Graham Davies, Tom Graham Davies

The World Health Organisation declared COVID-19 a global health pandemic in early 2020, with all countries affected to a greater or lesser extent. As of late June 2021, Indonesia had reported 1.9 million cases and over 54,000 deaths. However, these official figures should be treated with caution, if not outright scepticism, as COVID-19 testing is limited in Indonesia, and significant health facility disparities exist across the various municipalities.

Indonesia’s testing rate is one of the lowest in the world, with less than 50 people per 1000 being tested (as of late June 2021). A key reason for low testing rates is that the test is not free unless you are symptomatic and can access a particular clinic; otherwise the cost is prohibitive for many. Indonesia’s reported cases of COVID-19 must, therefore, be significantly higher than official figures suggest. Underreporting is thus of significant concern given that on 18 June 2021, Indonesia reported over 12,000 new cases.

Like many other countries, the Indonesian government has issued a policy to control and prevent the spread of COVID-19 in the form of Regulation Number 9 of 2020, concerning large-scale social restrictions, known as Pembatasan Sosial Berskala Besar (PSBB). This policy has proven to be only partially effective in slowing the increase in cases of COVID-19 infection, and the implementation and enforcement of PSBB varies starkly across regions. The government is now focused on its vaccination program, not on COVID-19 testing.

The impact of the pandemic and associated government-imposed large-scale social restrictions on Indonesia’s economy can be described as catastrophic. The East Asia Forum reports that in the last three quarters of 2020, Indonesia’s growth rate averaged less than negative 4 percent. This negative growth rate caused about two million more Indonesians to fall below the poverty line and unemployment to rise to around 7.1 percent (as of August 2020).

Unlike some of its richer neighbors, Indonesia can ill afford these impacts, and the government has been under constant pressure, particularly from business owners, to relax large-scale social restrictions. As a result, a more relaxed approach to COVID-19 is influencing perceptions of COVID-19 among the general population. Currently, central government has announced a further preventive approach called 'Pemberlakuan Pembatasan Kegiatan Masyarakat (PPKM) Mikro' or 'Micro-Scale Public Activity Restriction' by involving small districts, including kelurahan (villages) and kecamatan (sub-districts), and the police and military.

Downplaying the virus

The Indonesian government prioritised the economy (rather than health) in its response to COVID-19. This decision then led to the government and its media outlets presenting information downplaying the harms of COVID-19. It should be noted at this juncture that the decision to focus on the economy was, at least in part, due to capacity limitations of the government. Through its social media and online media platforms, in particular, the government has led the notion that COVID-19 is not particularly harmful to health.

In February and March 2020, the then Minister for Health Terawan Agus Putranto, made a series of controversial statements, that experts pointed out at the time underestimated the dangers of coronavirus. Some of Terawan’s statements included ‘we are not afraid of diptheria; of course we are not afraid of COVID-19’ (‘Difteri saja kita tidak takut apalagi korona’); ‘Flu is more dangerous than corona virus’ (‘Flu lebih berbahaya daripada virus korona’); and ‘masks are only for sick people’ (‘Masker itu untuk orang sakit’). As recently as October 2020, then still Minister of Health, Terawan, was reported to support the use of herbal medicines to treat COVID-19 and endorsed the Ministry of Health in its policy of using them in healthcare facilities. In late December 2020, Terawan was removed from his position as Minister in a cabinet re-shuffle, and replaced by Budi Gunadi Sadikin.

It should be noted that we are aware that analysing and presenting the above messages paints a picture of a unified government policy aimed at downplaying the impact of COVID-19. We do not believe that this is in fact the case. There are examples of policies at the central government level that are clearly aimed at reducing the impact of COVID-19. For instance, President Joko Widodo issued partial lockdown orders, encouraged social distancing as well as allocated budgetary resources to address the issue. Our focus is to highlight the contradictions within the narrative offered by the Indonesian Government and how they were interpreted by the Indonesian people.

Social media offers health experts the capability of conveying accurate and robust information about the hazards of COVID-19 quickly and to potentially large and dispersed audiences. At the same time, social media also provides a platform (and rewards) for countering expert knowledge and spreading misinformation and disinformation. The concept of disinformation is not limited to COVID-denying individuals acting alone, but is also used as a tool for propagating misleading narratives from institutions, including the government.

In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in January and February 2020, neighbouring countries Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia openly reported their first cases. In contrast, Indonesia did not officially report any cases at all. This is unsurprising. From the onset of the pandemic, the government’s public response to COVID-19 has tended to be one of denial and of playing down the dangers posed by the disease. In February 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) was concerned that Indonesia had not reported a single confirmed case in a nation of nearly 270 million people. Given the densities of Indonesia’s cities, COVID-19 cases were likely already numerous – and rising.

Indonesia’s early COVID-19 denial can be seen in the way the relevant government authorities said that they were testing people. In contrast to worldwide agreement about the dangers posed by COVID-19, on 11 February 2020, the Indonesian Minister for Health, Terawan Agus Putranto told media ‘They (other countries or experts) may not believe the reality (that Indonesian is zero COVID-19). But it is the truth; why do they think it is not reality?’ (‘Mereka boleh heran tapi itu kan kenyataan. Kalau kenyataan itu mau dianggap mengada-ada gimana’.)

On 2 March 2020, the government officially announced the first cases of COVID-19. As the disease gained ground, shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) for health workers became a worrying issue. Health workers reported having to wear raincoats as substitutes for PPE.

In January 2021, the new Minister of Health, Budi Gunadi Sadikin, acknowledged the mishandling of COVID-19 response strategies, stating that ‘we are now busy mopping the floor during rainy season, but we forgot to repair the damaged roof.’

Seeds of mistrust

Cognisant of the economic turmoil brought by the pandemic both globally and locally, by May 2020 the Indonesian government had backtracked from its original control measures. In April, Bank Indonesia had revised its projection for Indonesia's economic growth to fall by 50 per cent from the initial projection of 4.6 per cent to 2.3 per cent. Its COVID-19 strategy evolved into an official policy described as the ‘New Normal’. The ‘New Normal’ represented a reversal of large-scale social restrictions and was interpreted by many Indonesians as ‘back to normal’. We asked our respondents what they understood ‘new normal’ to mean:

Anti told us, ‘[With the] New Normal, we aim to return to normal activities, but still need to maintain our health’, and Eni explained, ‘New Normal is back to normal; the condition is getting better.’

A corollary of COVID-19 denial was the Indonesian government’s public information campaign, which was unclear. President Joko Widodo went on record saying that it was possible to have both strict health protocols in place and for people to go about their lives normally. In May 2020, he said ‘We must coexist with COVID-19’; the President’s advice seems to suggest that people can go back to living "normally" – but still must adhere to abnormal restrictions and protocols.

This confused and confusing official messaging contributed to COVID-19 denial gaining traction. The COVID-19 denial narrative began to play a role in how health professions in Indonesia were perceived. Many Indonesians began to believe that health professionals were over-diagnosing COVID-19 cases at health centers. Rumours spread that health professionals were profiteering by falsely diagnosing patients and requiring unnecessary and pricey COVID-19 tests. Questions were also raised in the media as doctors were accused of extracting economic benefits by asking every patient to get a COVID-19 test at a rough cost upwards of Rp 150.000 (USD $10), regardless of the presence or absence of symptoms. Given this circulation of misinformation, people became afraid to visit public hospitals at all out of fear of expensive misdiagnoses or unnecessary tests.

Local contexts

Economic pressures clearly played a part in undermining COVID-19 prevention measures. Anti-COVID policies, including PSBB, forced many people into choosing between risking infection by leaving home to earn a living, or staying at home and enduring conditions of deprivation and slipping into poverty. This impossible choice disproportionately affected Indonesian women, many of whom earn a living from vulnerable jobs in the informal sector.

Policies aimed at supporting those affected by the economic downturn, such as incentives worth 2.4 million rupiah (USD$200) for micro-businesses, were tricky to put in place because many jobs are not officially recorded (through taxation systems or otherwise). The Government of Indonesia lacks sufficient data about who is and is not entitled to receive this financial aid. Consequently, the government’s economic support has remained scattered, meaning that not everyone who needs it is receiving it, especially women.

The interpretation of religious teachings also plays a role in Indonesia’s COVID-19 response. The Islamic idea of 'tawakal dengan Allah' (God willing), is a belief that what will happen in your life or the future is in God’s hands. It follows, then, that people believe their lives are largely predestined to take a certain trajectory and that personal decisions may have little effect on the outcome of a person’s life. As such, nothing can be gained from taking responsibility for making decisions in terms of responding to COVID-19. In effect, the idea is that taking action to minimise harm will have little consequence since god’s will is all that matters – and COVID-19 and its consequences are part of that will. This understanding of religious doctrine challenged the government’s efforts to integrate preventive measures effectively into people’s daily lives. For instance, when we asked respondents why they did not wear a mask, they answered: ‘Death is in God’s hands; not due to Corona’.

Some religious leaders, however, provided effective guidance on keeping safe from COVID-19 by encouraging their followers to carry out early prevention. These leaders provided handwashing facilities and free masks in centres of Islamic gatherings, and it is interesting to note that the ritualistic ablutions before prayer in Islam synergise somewhat with COVID-19 guidelines.

Mixed messages

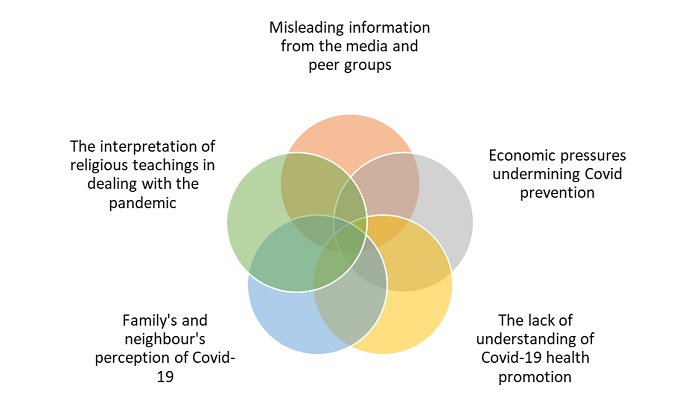

There are a range of sometimes competing understandings about COVID-19 within Indonesia, both at the central government level and at the individual level. We have shown that without clear and unified messaging from the government and national health bodies, people receive a range of mixed messages about the impact of COVID-19 and what measures should be followed to slow infection. These competing narratives surrounding COVID-19 created an environment of uncertainty for people seeking reliable information about the disease, including preventing its spread.

A year and a half into the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia, we believe there is no sign that the Indonesian government is serious about handling this case. At the policy level, contradictions still abound; for instance, earlier this year, the government prohibited traditional Eid al-Fitr homecoming at the same time the Ministry of Tourism and the Creative Economy began reopening tourism destinations. Now, Indonesia is experiencing a shocking resurgence of COVID-19; its highest-ever case increase was registered on 17 June, and all signs point to lax travel restrictions, both international and domestic (including during Eid al-Fitr), as the culprit. The Ministry of Health has focused on vaccine delivery and seems to be ignoring prevention strategies, such as case tracking and enforcing health protocols (which are starting to slip, as evidenced by high-profile, large public gatherings, including those attended by President Joko Widodo).

The lack of a unified message is compounded by low digital literacy rates across socioeconomic classes. Health messages are even further diluted by the presence of multiple and often contradictory ‘truths’ proliferating on social media platforms. Even if people understand the true dangers posed by COVID-19, without adequate resources, they can only do so much to protect themselves if economic necessity drives them out into the workplace to earn an income and survive.

Najmah (najmah@fkm.unsri.ac.id) is a lecturer in the Public Health Faculty of Sriwijaya University, South Sumatra, Indonesia. Sari Andajani (sari.andajani@aut.ac.nz) is a senior lecturer at the Department of Public Health, Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand. Kusnan (kusnan@student.inceif.org) is an international student in School of Graduates and Professional studies, INCEIF, Malaysia undertaking a masters in Islamic Finance. Sharyn Graham Davies is Director of the Herb Feith Indonesian Engagement Centre at Monash University in Melbourne. Tom Graham Davies (tomdavies16@gmail.com) has a PhD in Sociology and Planning from the University of Auckland in New Zealand.