Obituary of Ki Poedijono: dhalang (puppeteer), musician, dancer and gamelan teacher

Linda Hibbs

Javanese dhalang (puppeteer), musician, dancer and gamelan teacher in Australia for over 45 years, Ki Poedijono sadly passed away on the 30th of January 2021. The significance of the date (which changes according to the Balinese calendar) was not lost on family and friends, who observed that this was, in fact, Saraswati Day, celebrating the Goddess of Knowledge (including music, art and learning). This seemed very fitting for someone whose life was dedicated to passing on his knowledge of traditional music and performing arts.

Poedijono’s love and enthusiasm for traditional Javanese music and culture, not to mention his broad smile and endless energy, left a lasting impression on the hundreds of Australian gamelan students; the school children, who sat enthralled watching the shadow puppets; the Balinese living in Melbourne, whose culture he embraced; to audiences, who attended the many cultural performances. He lived for, and through, his passion for bringing Javanese and Balinese culture into Australian hearts.

Poedijono was born in a village in the regency of Wonogiri in Central Java in 1940 and was descended from a line of dhalangs, starting with his great-great-great grandfather. He recalled in an interview that his grandmother would accompany his grandfather on gender (one of the gamelan instruments) during wayang performances. His father and his father’s brother were also dhalangs and Poedijono recalled going to his father’s all-night performances when quite young. As his eyes became too sleepy to watch the puppets, and with the sound of the gamelan around him, he’d fall asleep right behind his father or even on his lap. At about eight years old he found himself actively involved when his father started asking him to hold or pass the puppets during a performance.

He also learnt to play the instruments of the gamelan by taking part in performances in his village. His father would give guidance from the side, telling him if he was playing it right or wrong. It was this gamelan that he would many years later introduce to two different groups of students he took from Melbourne to perform in Java. They were honoured to have the opportunity to play on the actual instruments that Poedijono himself had played as a young child growing up.

One day in 1948, when Poedijono was only eight, his father asked him to play gong during a performance. By nine years of age, his father trusted him to perform mucuki, a short introductory puppet section at the beginning of his father’s main performance. There were many very good and famous dhalangs performing in Central Java at the time and his father performed outside Wonogiri and travelled to Solo, Surabaya and elsewhere in East Java. They often performed for people who had migrated from central to east Java. During the late 1940s, there was little money to pay the dhalang for their performance. Poedijono recalled that food was always provided to them for offerings before the performance. At the age of ten, Poedijono also joined dance classes in his village.

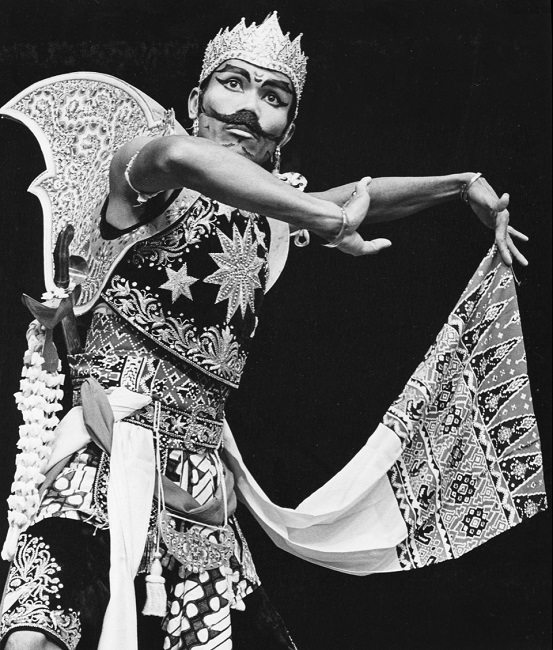

Poedijono then entered the specialist arts high school in Solo known now as SMKI (Sekolah Menengah Karawitan Indonesia). By the time Poedijono was about 16, he had already performed night-long performances in the Wonogiri area. It was also at this time that he was chosen as a dancer to perform in the regular Ramayana Prambanan temple dance performance.

One day Dr Panji, head of SMKI Bali came to Solo and asked if recent graduates would be interested in teaching Javanese gamelan, dance and wayang in Bali. With Poedijono’s fine ability as a dhalang, dancer, singer and gamelan performer, his teachers had no hesitancy in recommending him. He enthusiastically took up the opportunity and from 1964-1972 taught at the music Conservatorium in Bali. It was here that he created a one hour ‘Java-Bali’ Ramayana ballet, which combined dance, theatre and elements of both Javanese and Balinese cultures. He also become well known for his make-up techniques that combined both Balinese and Javanese characteristics. This style of performance was performed in villages around Bali and, in 1969, a troupe of musicians and dancers (including Pak Poedijono and his father-in-law, famous dancer and teacher, I Wayan Rindi) travelled to America to perform this style.

It was in Bali that Poedijono met Merthi, daughter of famous dancer I Wayan Rindi, an accomplished Balinese dancer herself, and one of Poedijono’s students. They married in 1968 and had two beautiful daughters, Eka and Ade, who have continued their father’s love of Javanese and Balinese culture.

After meeting Emeritus Professor Margaret Kartomi, who was then a lecturer in music at Monash University, in Bali in 1972, and visiting Melbourne at her invitation, he found himself teaching on instruments borrowed from the Embassy in Canberra, and presenting his first dance-drama performance at Monash University. Returning in 1973 to an on-going position at the university and bringing his family, he made Australia his new home. After a couple of years of creating these large-scale dance-drama performances for school students during the day and general public at night, enough money was raised to buy a full gamelan set for the university – the first full set in Australia. Some classes were part of the ethnomusicology program and some were part of lunchtime classes, attended by students from other faculties and interested staff.

Finding dancers for the annual dance-drama was often difficult in those early days, and as with all student groups the gamelan musicians would come and go. But each year for the more than 20 years that Poedijono taught at Monash, there was always an end-of-year concert combining Javanese gamelan (later years including Balinese gamelan), dance (Javanese and later Balinese as well) and shadow puppets, taken from the stories of the Ramayana and Mahabharata and presented in a mix of Javanese, Indonesian and English. Some of the dancers in the early days included Poedijono himself, Cathy Mardisiswoyo and Margaret Kartomi’s husband, Hidris Kartomi. Even Indonesian lecturer Basoeki Koesasi made an appearance. Over the years there were many others who joined in these dance performances. One year he taught local high school students the Balinese kecak vocals and combined with Merthi dancing, they created their first kecak in Australia in the Robert Blackwood Hall.

Poedijono later helped to set up numerous gamelans in Victoria and other states, including South Australia and Tasmania. He toured Tasmania with the Monash gamelan in 1978 and 1982. He also travelled overseas, including to Noumea, where he described the amazing reception he received and the overwhelming emotion from some of the local Javanese living there, who had not heard gamelan or seen a wayang performance for over 40 years. ‘They hugged me with tears in their eyes’, he recalled. Another overseas highlight was a performance in Hong Kong that was attended by over 3000 people.

Poedijono also started teaching gamelan at Melbourne State College during the 1980s and then in the late 1990s moved from teaching at Monash University, to teaching students at the University of Melbourne in the music program run by Emeritus Professor Cathy Falk.

Pak Poedijono loved performing wayang for children. In them he found an innocence and a spontaneity that was different from adults. Their favourite joke centred around the clown puppet Petruk. They laughed loudly when Poedijono made Petruk’s ponytail flip about and they especially loved his ‘long name-short name’ scenario. When a puppet asked his name, Petruk would smugly ask if they wanted his short or long name and then give a short quipped ‘Truk!’ or provide his ‘long’ name, stretching the sound ‘Petruuuuuuuuuk’ as long as possible. This endeared the children to the puppets and puppeteer. It was wonderful to see children clamber up on the stage afterwards to meet him and to ask question after question about the puppets. Poedijono spent a lot of time each week travelling to different schools to perform and to help some schools set up a gamelan. He was especially sought after by schools teaching Indonesian language. For so many Australians, this was their first taste of Indonesian culture.

He was also instrumental in starting three community groups in Melbourne: Melbourne Community Gamelan in 1990, Permai in 1993 and Yarragam in 1999, as well as an all-female group based at the Indonesian Consulate in Melbourne. He also set up and led the Balinese community gamelan group Mahindra Bali and helped his wife, Merthi, establish the Balinese Dance Society in 1995. In 1996, Poedijono and a group of Melbourne gamelan musicians travelled to Yogyakarta to participate in the International gamelan Festival. They were referred to as ‘the classical group’ as Poedijono had not wanted to incorporate any new or developing gamelan trends. He did, however, compose some gamelan pieces himself including one that was called ‘Yarra’ – referencing the Yarra River that runs through Melbourne and this became the ‘theme song’ for the group YarraGam (a play on the words Yarra and Australian Gum trees and Gamelan). Another composition included the sound of a Melbourne tram. He composed a signature tune for each group.

Longer wayang performances were staged outside and inside venues at the University of Melbourne and included guest dhalang; Ki Joko Susilo, from New Zealand; Nyi Suharni Sabdhowati from Sragen, Central Java; and local Melbourne dhalang trained in Central Java, Helen Pausacker. An annual event ‘The Final Gong’ was set up for gamelan students at the University of Melbourne to perform, alongside performances by the other Javanese and Balinese groups in Melbourne.

As Poedijono’s health declined in later years, he was unable to lead and then participate in these performances. Melbourne Community Gamelan has continued with musicians, who have trained in Java such as Aline Scott-Maxwell, Michael Ewing and Helen Pausacker and under the leadership of Ilona Wright, who first studied with Pak Poedijono as an undergraduate and later studied kendhang (drum) in Java and took over Poedijono’s role of teaching gamelan at the University of Melbourne. Helen Pausacker continues to perform as a dhalang and with plans for guest artists and dhalangs from Java in the future, the group hopes to continue the legacy of Pak Poedijono.

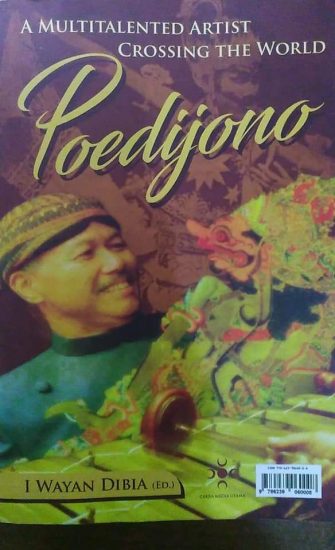

In 2003, Poedijono was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia (OAM) for his services in promoting Indonesian culture in Australia. In 2007, the Indonesian government granted him the prestigious Satya Lencana medal, the highest award in the field of culture, for his sustained dedication in promoting Indonesian arts and culture in Australia. A biography by I Wayan Dibia, entitled Poedijono, A Multitalented Artist Crossing the World, was published in 2019.

Poedijono has left a significant and important musical and cultural legacy in Melbourne. He will be remembered not only as the first but the only Central Javanese gamelan teacher in Melbourne or even Australia, who taught for over 45 years and influenced many to continue to pursue further studies in gamelan both here and in Java or Bali. His vibrant personality along with his enthusiasm and dedication to bringing Javanese and Balinese culture to Australia will be sorely missed. He is survived by his wife, Ibu Merthi, daughters Eka and Ade and their families.

Linda Hibbs (lhibbs@ihug.com.au) studied ethnomusicology at Monash University and played in various gamelan groups in Melbourne for over 25 years, and more recently has written several books on learning Indonesian language and culture.