Keith Foulcher

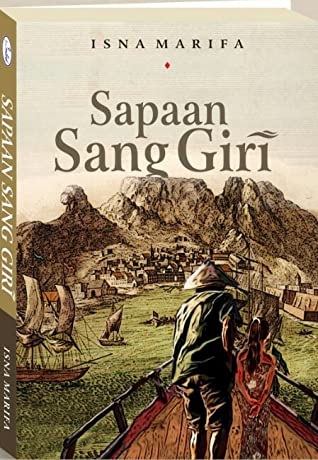

In the opening pages of Isna Marifa’s debut novel, Sapaan Sang Giri, a young Javanese girl awakes to the sound of her father’s voice intruding on her dreams. ‘Come, my girl, get up!’ he calls. ‘Come and see. The ship’s coming into port.’ The year is 1751, and father and daughter have been at sea for months, deep in the hold of a Dutch ship as it crosses the ocean between Batavia and the southern tip of Africa. Life in her Javanese village now no more than a distant memory, Wulan and her father Parto are about to embark on a life of servitude to a wealthy Dutch family in Cape Town, joining the ranks of the bondsmen and women who would become the ancestors of today’s diasporic community of ‘Cape Malays’ in multicultural South Africa.

Wulan speaks to the novel’s reader in verse, one of three narrators who tell this story of dispossession and suffering, of unrequited longing for home, but also of resilience and the strength of community. The other narrators, who speak in modern Indonesian prose liberally interspersed with Javanese words and phrases, are Parto – who accepts a life of servitude rather than surrender his ancestral land in the face of crippling debt – and Wulan’s grandfather Wage – who watches on as a new world order begins to intrude on life in the shadow of Java’s majestic mountains.

With no family other than his nine-year-old daughter, Parto has left the mountains of Java for life in the shadow of another mountain half a world away. From now on, it will be Table Mountain that dominates his life, watching over him and his daughter just as Gunung Ungaran and its neighbours look down on those who remain behind in the villages of Java. In both cases, the title of the novel suggests, the mountains are like guardian spirits, extending a benevolent gaze over those they nurture and protect.

In the course of her life so far from home, and with the longing for home never far from her mind, Wulan has two children by different fathers, a boy and a girl. They take pride in their Javanese heritage even as they begin to assume a new identity as members of a multicultural community of exiles, people who are forging a new life for themselves, far removed from their ancestral lands. Even though their community is founded on the ravages of colonialism, they and their peers carry within them the seeds of what will one day become a forward-looking transnational world – a development that is outside the time frame of this story, but which is hinted at in its conclusion. The final voice the reader hears is that of Wulan’s son Abi, who adopts the verse form his mother uses early on in the narrative in the novel’s tightly-worded epilogue:

I stand here between

the blue bay and Table Mountain

my skin is neither as dark as the Africans’

nor as pale as that of the Europeans

who came to conquer this land;

my grandfather, my mother,

they too came from afar,

and though they came in chains,

they spread compassion in their wake.

I stand here between

the mountain and Table Bay

on the slopes outside Cape Town;

I was born nearby

and I will die here too

as a free man

I proudly bend in prayer

with my own people

in the mosque we owe to the efforts

of our founding teacher

who stood up to the Dutch

and the English, who vanquished them.

I am Abi van der Kaap,

a true citizen of Cape Town,

my grandfather and my mother were born in Java

now they rest in the embrace of African soil.

I am Abi van der Kaap,

a free man.

Sapaan Sang Giri’s two hundred pages span a time frame of nearly fifty years, a period intersecting with the foundation of another diasporic community that was to become a nation founded on the dispossession of indigenous people by colonial expansion, the Commonwealth of Australia. In 1787, a fleet of English ships carrying a party of convicts and marines charged with founding a settlement on the east coast of Terra Australis put ashore in the English colony on the southern tip of Africa where Isna Marifa’s characters were living out their lives. Interestingly, the English fleet’s Surgeon-General, John White, left an account of his stay in Cape Town that included a comment on their condition. White had earlier spent three years in the British West Indies, where he had been ‘sickened’ by the British treatment of the colony’s slave population. In Cape Town, however, he found that the Dutch treated their slaves with ‘great humanity and kindness’, in stark contrast to the cruel punishments they inflicted on delinquents among their own compatriots. Whether or not White’s ‘great humanity and kindness’ is reflected in the lives of Wulan, Parto and their fellow Javanese in the Cape in 1787, is best left up to the reader to decide. That should be part of the pleasure of exploring the many dimensions of Isna Marifa’s narrative.

There is one aspect of the author’s intentions, however, that is worth stating explicitly in conclusion. It informs, rather than detracts from, our encounter with Sapaan Sang Giri to know that it was inspired by visits Isna Marifa made to Cape Town in 2015 and 2017. During these visits, Isna came into contact with members of the Cape Malay community, an encounter that left her with the determination to contribute to her new friends’ knowledge of their ancestral heritage. In an online discussion soon after the novel’s publication , Isna explained that her motivation for writing Sapaan Sang Giri was her desire to record something of the ‘essence’ of the Javanese people for the Cape Malay community. She wanted to inform Cape Malays with Javanese heritage about their roots, to contribute to their knowledge of where they came from and who they were.

For Isna, these people are the bearers of an ancient and proud culture, a heritage which lies at the heart of their identity, just as it pervades the lives of the Javanese people of modern Indonesia. Knowing something of this motivation is important, because it helps us understand the Javanese ‘flavour’ of the novel, from its many references to Javanese cultural practices and classical texts to its Javanese-influenced Indonesian vocabulary and style. Until and unless it appears in English, Sapaan Sang Giri will unfortunately remain beyond the reach of the people of modern South Africa who are its intended audience. Unmistakably, however, these people lie in the novel’s shadow, just as its characters and the people of their time are watched over by the great mountains evoked in its title. (‘Hello Says the Mountain’ is Isna’s working title for an English version.)

In Sapaan Sang Giri, Isna Marifa has extended the geographical and emotional reach of the modern Indonesian novel. The result is an original and captivating story that has launched the career of a new and promising literary voice. Her readers will be eager to see where her explorations take her next.

Isna Marifa, Sapaan Sang Giri, Penerbit Ombak, Yogyakarta, 2020. The novel is also published in English as Mountains More Ancient, Kabar Media, 2022.

Keith Foulcher (keith.foulcher@sydney.edu.au) is a translator and writer and an Honorary Associate of the Department of Indonesian Studies at the University of Sydney.