Indonesia needs to acknowledge that it too has a problem with racism

Indonesia needs to acknowledge that it too has a problem with racism

Tamara Soukotta

In the early 2000s, I was working as a volunteer for an NGO in Jakarta, assisting West Papuan students in Java and Bali in their quest for legal justice. These efforts followed several cases of human rights abuses in West Papua, including the Abepura incident that took place in December 2000, in which police stormed a student dormitory killings several and triggering unlawful arrests and further violence.

At one point, the West Papuan students we were supporting requested an audience with members of the parliament in Jakarta. Only a few were appointed to take part in the meeting, but all the students who already gathered in Jakarta decided to march together to the parliament as a way to draw public attention to the endless violence in West Papua.

As we waited for the relatively small group of students to reach the parliament, a colleague and I sat in a warung just by the gates to the parliament building in Senayan. Two men in dark coloured clothing and short cropped hair and carrying radios entered the warung – their appearance signalled to both of us that they are ‘intel’. The food seller greeted them and asked if they were expecting a protest. The men replied in the affirmative. The food seller then asked who they were expecting, to which the men replied, ‘the usual monkeys, those Papuans and Timorese’. This comment was made so casually, even with a laugh. Perhaps they were oblivious to our presence or simply did not suspect that two young women who looked like us would have any association with the expected ‘monkeys’, they continued their conversation with the food seller.

Upon hearing of word ‘monkeys’ my colleague and I both became red with anger. The word ‘monkey’ and other dehumanising terms were (and are still) commonly used to describe West Papuans, East Timorese and people from the eastern part of Indonesia in general. Our visceral response to hearing these men that day was partly because we had spent days and nights listening to heart-breaking testimonies about experiences of violence in West Papua that mostly occurred precisely because they were not considered to be human beings in their own land.

For me, there was an additional reason to burn with anger. I myself am one of those monkeys, as I came from Maluku, a neighbouring province to West Papua. They did not feel the need to filter their words in my presence though, for I did not look the part. My skin is not very dark and my hair is not stereotypically curly, so I can ‘pass’ as a Javanese.

While this was not the first racist incident I experienced in Indonesia, this one slapped me across the face. It taught me at least two things: the depth of racism in my country, and the privileges that I have – privileges that allow me to pass as ‘human’ and to walk in the crowd without my origin being noticed, which in the end translates to more chances that I will avoid racial-based abuse and violence in my own country.

Being able to pass as Javanese or any other ‘regular’ Indonesian in Jakarta was particularly crucial during the years of conflict in Maluku that ran from 1999-2004. Even before the war, as Malukans we already lived with the stereotype of being ‘preman’ or thugs, muscles without brains who fight others’ battles as long as they are paid well. This stereotype has its roots in colonial history, where under Dutch rule Malukans were forcedly employed and used as soldiers to crush resistance in other parts of Indonesia. This led to Malukns being given the label ‘anjing Belanda’ (Dutch watchdog). Being able to ‘pass’ as ‘regular’ Indonesian meant I was saved from constant questioning and suspicion regarding the conflict in Maluku at that time.

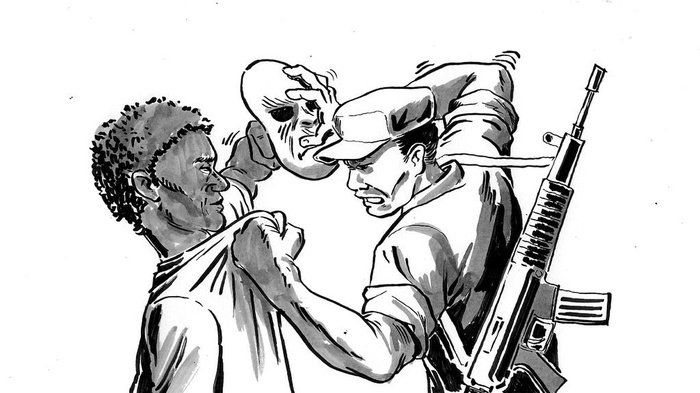

A structure of oppression

Derogatory labels like ‘monkey’ and ‘thugs’, do not appear out of nowhere. They have their historical roots in the experience of colonialism that created a structure of racism in which a group of people is seen as more human than other group(s) of people, and therefore have the right to determine the lives of those deemed less human. Simply put, under Dutch colonialism in the Netherlands East Indies, the white European colonisers were the human and the dark-skinned inlanders the sub-human. Following Indonesian independence, with the power of the new nation-state centred in Jakarta and increasingly dominated by those from Java, racism was reproduced and the rest of the country ranked according to a hierarchy that determines their humanity, and consequently the value of their lives.

Racism as a structure of oppression is based on a hierarchy where the darker one is perceived to be, the less human and therefore the less valued one’s life is. It is within this structure that people from the eastern part of Indonesia (Timor, Flores, Maluku, West Papua among others) who are generally – or rather stereotypically – darker than other parts of Indonesia are deemed less human, hence the ‘monkey’ label. In the case of West Papua, at its most severe, racism has claimed the lives of many who were shot dead at the hand of the police and military personnel, with bullets funded by the state – not so different than the experience of African-Americans and indigenous Americans in the United States.

Unfortunately, such arbitrary deadly violence committed with impunity is only one of many forms of racism in democratic Indonesia. There are other forms that are often less visible and therefore might be considered less brutal, or not necessarily considered as violence at all. These include deaths caused by negligence: such as deaths due to lack of access to proper healthcare, death because of famine and malnutrition due to failed crops and lack of access to water as well as other resources, death because of the rampant spread of HIV infections as in the case of West Papua.

Other forms of racism take the guise of good intentions. Critics of Development projects initiated by the government as well as NGOS for the ‘improvement’ and ‘betterment’ of communities who are deemed backward, primitive, and uncivilised, point out that these are in themselves racist categories. Similarly, projects aimed at ‘saving’ these communities from their ‘sad predicaments’ would also be racist. Since they are meant ‘for the good of the people’, and as Development projects in general are seen as ‘good’, the racist undercurrents are overlooked. Sadly, these forms of racism can lead to displacement, marginalisation, criminalisation and even death without protest.

A range of projects carried out in the name of Development have been found to have had detrimental impacts on West Papuans in particular but also other indigenous communities in Indonesia. These include education targeting indigenous communities with the purpose of ‘taking the savage out of the man’; (forced) relocation of indigenous communities from their land/mountains/forest to new government-built settlements; and investment in tourism projects that resulted in local communities being forced off their land. These and other state and privately-funded projects are promoted as to providing income and a better livelihood for local communities, but at their core they benefit the state and private corporations at the expense of the indigenous communities.

Still taboo

Despite this harsh reality, as Indonesians we rarely talk about racism in Indonesia. As scholars doing research or activists working on advocacy on the ground, we don’t necessarily use the term racism to address problems such as different ‘treatment’ experienced by West Papuans or the lack of access to healthcare for indigenous communities. At most we might talk about discrimination and marginalisation, but not the racism that leads to discrimination, marginalisation and other forms of violence.

It is easier perhaps, to see racism in other contexts—the United States of America being the most obvious, or perhaps South Africa and even Europe, but not in the case of Indonesia. This might be due to misunderstandings of race and racism, in which racism is seen as something that exists only in the context where there are White people and Black people such as in the United States of America, and there cannot be applied in the context of Indonesia. At the same time there is another possibility – a rather scary one – that as individuals we believe that so long as it does not concern us directly, then why bother to ask questions or even to think about it?

In the midst of global struggle to end racism where do we stand in Indonesia? When even direct killings of protesters, such as in the case of West Papua, are hardly questioned, can we expect these other forms of racism to be challenged? If yes, how and by whom? Perhaps we could start by acknowledging that racism does exist in Indonesia, that it is a problem, and a serious one in fact. Then we can have more conversations – open and honest conversations – about racism, oppression that some experience at the hand of others, privileges that some of us have which allows us to escape the violence and perhaps even benefit from others’ oppression. If we found it reasonable to take part in the #BlackLivesMatter movement and demand justice for the deaths of many young black men in the United States of America, perhaps it is not too much to hope that we can also start making efforts to address racism at home.

Tamara Soukotta is a PhD Researcher at The International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) of Erasmus University Rotterdam and a Lecturer in International Studies, Leiden University.