An essential resource for Indonesian history scholars and students, Kartini's works are now available by open access

In 1904, shortly after the sudden death of Kartini, editor of a Yogyakarta-based feminist publication, De Echo: Weekblad voor dames in Indië (1899 – 1905), Mev. Ter Horst de Boer, published a tribute to her in a leading colonial newspaper. Ter Horst was an outspoken progressive and feminist, making her a particular minority in the European colonial context. She had founded the short-lived weekly to circulate and publicise feminist ideas from Europe, and to provide a forum for women in the colony to discuss them and contribute articles.

In 1900, Ter Horst was corresponding with Kartini (and sending her complementary copies of the publication) to encourage her to write about her ideas on the emancipation of Javanese women for the journal’s European readers. This was to take the form of two lengthy accounts that revealed aspects of the 'revolutionary' life she was leading, published under the pseudonym 'Tiga Saudara' in 1900. For the first time, Ter Horst’s obituary to Kartini, translated by Joost Coté, is published as an extract here. It emphasises how Kartini was not wanting to 'become European', but to provide Javanese women with the tools of European feminism to transform Javanese society.

It was as though the entire women’s world in the Indies were thunder struck on hearing about the death of R. A. Kartini, wife of the regent of Rembang and oldest daughter of the regent of Japara. I do not need to explain who Kartini was; every European and Native woman with some education here in Java now knows about her. A princess by birth and as well extraordinarily sophisticated and talented, Kartini was conscious of the fact that with her gifts she had been called to pave the way for her Javanese sisters to experience a life more befitting of human beings. All of us who live here, who know the position of the Javanese woman in society, will recognise the gigantic task that she had chosen to undertake, and how thorny that path would be. Nevertheless, Kartini knew that, even though she would never be able to fully realise her aims, she would be able to do much to bring these about.

Kartini was loyally supported by her younger sisters, Raden Ajeng Kardinah, and Raden Aleng Roekmini, while her parents did as much as they could to advance the plans of their talented daughters, the 'Tiga Saudara'. How much the trio appreciated their help one can read about in the sketch which, at my request, she wrote for De Echo, following her visit to Semarang to participate in the celebration of the Governor General’s Day [in May 1900]. After giving us a brief insight into the domestic life inside the kabupaten Japara, we are able to read about the preparations made for this amazing event: a public festivity that three girls, daughters of a regent, of high aristocracy, would be allowed to participate in. Only after experiencing the joy of the journey and the beauty that she saw on all sides, only then did she come to realise how privileged she was more than any of her sisters – the daughters of other Native regents. It was at this formal occasion that Kartini formulated her great plan, to do as much as she could to enable other Javanese girls from the higher circles to experience more of the joy of life, so that they too could be as happy as she herself was.

For a long time the daughters of the Regent of Japara have been known as extraordinarily talented, inspired by progressive ideas. …. Increasingly it was Kartini, as the eldest, who came to the fore, but it seemed to me that her sisters agreed with her, and that their views were the same as hers.

Sadly, it was not possible for Kartini to complete her work as she had envisaged it. After the marriage of Kardinah, the two other sisters planned to establish a boarding school for the daughters of Native leaders, but the problems related to this proved too great, and they had to limit themselves to working to achieve their goals in a smaller circle. Every child in Japara will be able to tell you with how much love they undertook this work. ….

It has been said that, because of her progressive liberal ideas, she had actually outgrown her own people. But this is a serious misconception. She was Javanese from top to toe; its language, its country, and the clothing of her people, were dear to her, and it was out of this love for her people that the idealistic plans to make her people happy came forth. On my asking her why she was so concerned to give her Native sisters more education and more European ideas, she told me that she and both her sisters had experienced the good that came from it. It was true it would deliver them unfortunate moments, but she was convinced that in time the children, and especially the sons, would experience the benefits. When the mother was able to join with their sons in being educated, the son would respect her more, and where he revered the mother, he would also respect more his wife.

It is certainly extremely sad that Kartini should pass away at such a young age soon after she gave birth to her first son. May the good seeds she has sown bear much fruit, and may that son one day become as his mother had hoped that he would become, and for which she had fought and suffered.

Ter Horst de Boer, Jogya, October 1904

Reading Kartini

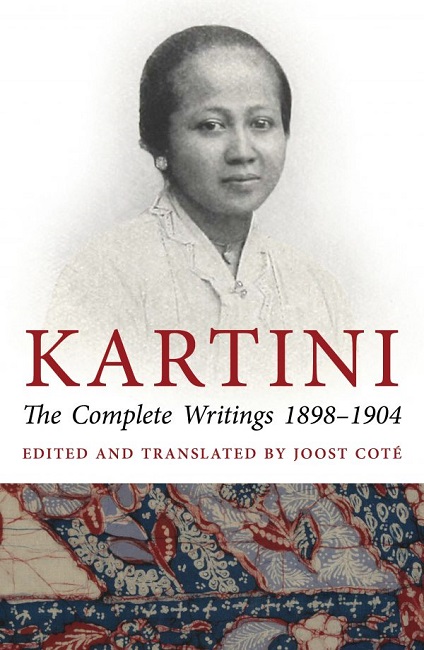

In Indonesia, the legacy of Raden Ajeng Kartini (1879–1904) is celebrated on Kartini Day, 21 April, every year. Around the world Kartini is recognised as a major figure in the history of the advancement of women: a tireless and effective advocate of women’s education and emancipation. In 1964 she was elevated to the status of national hero by Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno. She has become one of the most well known Asian figures in the international women’s movement.

To coincide with the Indonesian national holiday, Kartini Day, on 21 April 2021, two edited volumes, one of her writings and another containing letters she exchanged with her sisters, have been made available for digital open access. Both are edited and translated by the leading scholar of her work, Joost Coté.

Kartini: The Complete Writings, 1898–1904 (Monash University Publishing, 2014) is the first complete and unexpurgated collection of Kartini's published articles, memoranda and correspondence ever published in any language. The edited volume demonstrates how Kartini strategically employed correspondence at the beginning of the 20th century to generate a wide circle of influential contacts in her campaign to gain political attention and support for her campaign for Javanese emancipation. The volume also reveals the many literary modes through which Kartini gave voice to her aims and ideals, as a writer of ethnographic papers and political tracts, and author of a number of published short stories. Not least, it reveals a Javanese intellectual widely read in contemporary Dutch literary and political genres. Reading Kartini will make clear why the world should remember her.

This collection reveals Kartini's importance as a pioneer of the Indonesian nationalist movement. Claiming in her letters and petitions her people's right to national autonomy well before her male compatriots did so publicly, Kartini used her writing in an attempt to educate the Netherlands and Dutch colonialists about Java and the aspirations of its people. Had she lived, she would have been one of Indonesia’s leading pre-independence writers as well as an educationist.

Realizing the Dream of R. A. Kartini: Her Sisters’ Letters from Colonial Java (Ohio University Press, 2008) presents a unique collection of documents reflecting the lives, attitudes, and politics of four Javanese women in the early twentieth century. Joost J. Coté translates the correspondence between Raden Ajeng Kartini, Indonesia’s first feminist, and her sisters, revealing for the first time her sisters’ contributions in defining and carrying out her ideals. With this collection, Coté aims to situate Kartini’s sisters within the more famous Kartini narrative–and indirectly to situate Kartini herself within a broader narrative.

The importance of the sisters of Kartini is often overlooked. However, their correspondence is significant, both because of the authentic detail their letters provide on the historical background to Kartini, and in their own right, in telling us how they interpreted and lived the aims Kartini articulated when she was alive. Each extended 'the dream of Kartini' (which in fact they helped define) in their own way and have their own important stories to tell about Indonesian women’s emancipation.

The letters reveal the emotional lives of these modern women and their concerns for the welfare of their husbands and the success of their children in rapidly changing times. While by no means radical nationalists, and not yet extending their horizons to the possibility of an Indonesian nation, these members of a new middle class nevertheless confidently express their belief in their own national identity.

The digital versions are available by open access here and here.

Related articles from the II Archive

Review: Kartini's complete legacy

Kartini: Anthology of poems

Review: Four perspectives on Hanung Bramantyo's Kartini

Women and the nation