Reality often falls short of expectations

Versi Bahasa Inggris

Usman Hamid

Indonesians take great pride in the national motto, Bhinneka Tunggal Ika – Unity in Diversity, and the country’s image as a tolerant and pluralist nation. In practice, however, reality often falls short of expectations, and double standards persist in both the state’s and the public’s treatment of certain minority ethnic groups.

In Indonesia several laws ostensibly provide protection for minorities: Article 156 of the Criminal Code, for example, prohibits publicly expressing feelings of hostility hatred or contempt against a particular race, religion, ethnicity or nationality in Indonesia.

Article 28, clause 2 of the controversial Electronic Information and Transactions (ITE Law) similarly prohibits the dissemination of information 'aimed at inflicting hatred or hostility against individuals and/or certain groups based on ethnicity, religion or race'.

Law No. 40/2008 is even more explicit about 'eliminating racial and ethnic discrimination', detailing a number of discriminatory actions that are punishable by Law up to five years imprisonment.

On paper these laws provide ample protection for minority groups as well as significant deterrents and punishment for racist and discriminatory behaviour. Yet these regulations offer little protection to minorities, and in practice, such laws are more often used against minorities, discriminating and marginalising even further already vulnerable groups.

To better understand how these laws- and the justice system in general - have disproportionately targeted minorities, the experience of two of the most discriminated racial and ethnic groups in the country, Papuans and Chinese Indonesians, provide a case in point.

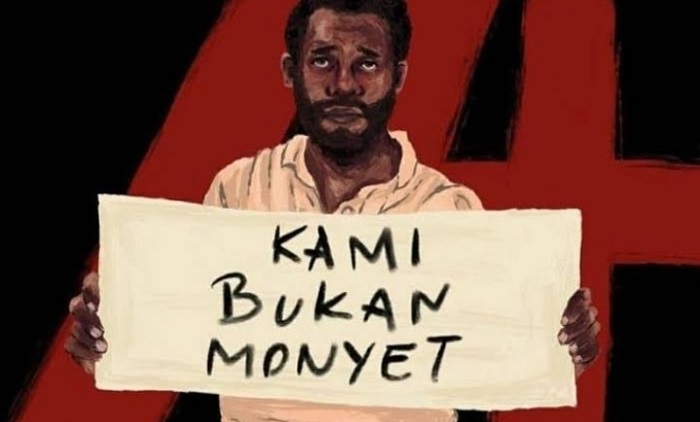

'As if we were half-animal'

Papuans have faced racial abuse from other Indonesians since their home region was incorporated into Indonesia in July 1969. Many Indonesians considered Papuans to be 'primitive' and less intelligent, as can be seen in the portrayal of Papuans in Indonesian films and television shows. In a 2020 article, media watchdog Remotivi noted that even recent movies such as Denias, Senandung di Atas Awan (2006) and Lost in Papua (2011) depicted Papuans as 'primitive, stupid, and violent'.

This negative perception is further complicated by stark political and religious differences that make it easier for Papuans to be treated as an 'other': many Papuans believe that Papua was illegally incorporated into Indonesia and crave independence, conflicting with the nationalist idea of a Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia (NKRI); Papuans are also predominantly Christian, while the rest of Indonesia is majority Muslim.

In his 2014 memoir, Seakan Kitorang Setengah Binatang (As If We Were Half Animal), Papuan activist and former prisoner of conscience, Filep Karma, states that throughout his childhood in Papua as well as his time as a university student in Java, he and his fellow Papuans were treated like they were not fully evolved humans by non-Papuans. 'Papuans were often called, "Monkey! Armpit!" Like that', he writes.

Such racial abuse continues unabated to the present day, with a number of high-profile incidents taking place in recent years.

In August 2019, security personnel and local mass organisations surrounded a Papuan university student dormitory in Surabaya, East Java, accusing the students of refusing to celebrate Indonesia’s Independence Day. Uniformed military personnel allegedly shouted slurs and curse words like 'monkeys', 'pigs' and 'dogs' at the students while banging on the dormitory gate.

Five soldiers were suspended for their involvement in the incident but no further action has been taken against them. Tri Susanti, one of the leaders of the mass organisations that besieged the dormitory was initially charged under both the ITE Law and the Racial Discrimination Law but was later convicted only of violating the former, receiving a seven-month prison sentence. No one else was convicted for participating in the incident.

More recently, Natalius Pigai, an ethnic Papuan, also a former commissioner of the National Human Rights Commission and outspoken government critic, has been the target of racially-tinged insults from pro-government supporters. In a picture posted on Facebook, Ambroncius Nababan, the head of a pro-government volunteer group, compared Pigai to a gorilla because of remarks he had made expressing doubts about the efficacy of the Sinovac COVID-19 vaccine that the Indonesian government has purchased from China, and which it has already begun to administer.

Meanwhile, in early January 2021 University of North Sumatra (USU) professor Yusuf Leonard Henuk posted a tweet comparing Pigai to a monkey.

The posts illustrate the deeply ingrained casual contempt and derision that is reserved for Papuans in Indonesian society - while political polarisation has reached new highs over the past few years, non-Papuan government critics have never been subjected to disparaging comparisons with apes and monkeys.

Nababan has recently been named as a suspect under the Racial Discrimination Law, though no law enforcement action has been taken against Henuk at the time of writing.

The apparent reluctance of state officials to take action against racial abuse against Papuans stands as a stark contrast to the swift and decisive measures taken when Papuans, or pro-Papuan activists, find themselves on the other side of the justice system.

In 2020, twelve Papuans and one non-Papuan activist were found guilty of treason for their participation in peaceful anti-racism protests in Jakarta and Jayapura.

The most high-profile charges of treason brought against anyone in Indonesia prior to this case was against a group of people accused of plotting to kill several high-ranking government officials in the wake of the 2019 election.

Veronica Koman, a human rights lawyer and an outspoken advocate for Papuan rights, was also charged with violating both the ITE Law and the Racial Discrimination Law for allegedly 'provoking' the widespread anti-racism protests that sprang up in Papua and across Indonesia in the wake of the Surabaya incident. Over the past two years, she faced harassment, intimidation, including death and rape threats.

Blacklisted by government, she had been asked by the Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP), a government-funded scholarship program under the Finance Ministry, to return scholarship money for her master’s degree studies. Koman, who is now in exile, is of Chinese descent - another group that faces systemic and widespread discrimination in Indonesia.

'Ganyang Cina' (Crush the Chinese)

Like Papuans, Chinese-Indonesians have long been subjected to racist abuse and discrimination - in this case dating back to the Dutch colonial era.

Stereotypes of Chinese-Indonesians as rich, power-hungry, greedy, selfish and corrupt have persisted from colonial times to the present day, with government regulations explicitly targeting Chinese-Indonesians remaining in place until 2000.

Presidential Instruction 14 of 1967, for example, banned Chinese literature and culture, prohibited the use of Chinese characters, and strongly advised Chinese-Indonesians to adopt Indonesian-sounding names.

While overt anti-Chinese racism is now generally frowned upon in the public sphere, and Chinese-Indonesians have access to more opportunities than in the past, the anti-Chinese rioting that erupted in the midst of pro-democracy protests in 1998 has continued to loom large over the community – the threat of violence is present any time someone of Chinese descent is deemed to have ‘overreached their position’.

And as with Papuans, any perceived misstep on the part of Chinese-Indonesians is swiftly met with law enforcement action, while criminal action against Chinese Indonesians is often overlooked.

A prominent case in point is the conviction of former Jakarta Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, better known as Ahok, under Article 156 of the Criminal Code. Ahok, a Christian of Chinese descent, was deemed to have insulted the Quran when he said that people were using a specific Quranic verse to 'deceive' voters.

While the groups that organised the massive anti-Ahok protests in the wake of his remarks portrayed themselves as 'defending Islam', the demonstrations were marked by widespread anti-Chinese sentiment. Some protesters, alongside politicians who joined the street protest, put up banners with the words 'Crush the Chinese' (Ganyang Cina) and many shouted slogans calling President Joko Widodo, a close ally of Ahok, a 'Chinese stooge' (antek Cina).

Following a protest against Ahok in November 2016, rioting and looting broke out in Penjaringan, North Jakarta – a neighbourhood with a large Chinese-Indonesian population – raising the spectre of May 1998.

No discrimination charges were brought against the protesters and rioters, nor were any brought against former student activist Sri Bintang Pamungkas, who referred to Ahok as a 'Chinese bastard'.

Another case that drew national and international attention is that of Meiliana, an ethnic Chinese Buddhist who was also found guilty of violating Article 156 in 2018. Her crime? Complaining about the loudspeaker volume of the adzan (call to prayer) in her neighborhood in Tanjung Balai, North Sumatra.

Her comment triggered a series of events that ended with arson attacks and the ransacking of 14 Buddhist temples in the city, in another echo of the 1998 riots - causing many ethnic Chinese residents to flee Tanjung Balai in fear for their lives.

Nineteen people involved in the rioting were charged with looting, destruction of property and inciting violence– none were charged with racial discrimination. The perpetrators were handed down sentences of between one to four months’ imprisonment. Meiliana, meanwhile, was sentenced to 18 months’ imprisonment for blasphemy under Article 156. She and her family have since moved from Tanjung Balai to Medan.

Miles to go

The cases mentioned above are just a small cross-section of how the legal system continues to turn a blind eye to offences perpetrated against minority racial and ethnic groups, while simultaneously responding to perceived slights by those same groups, in an excessive and discriminatory manner.

According to data from the Southeast Asia Freedom of Expression Network (SAFEnet), since 2011 at least 77 people have been charged with violating Article 28 clause 2 of the ITE Law, which bans the electronic dissemination of information 'aimed at inflicting hatred or hostility against individuals and/or certain groups based on ethnicity, religion or race'. Of these, few, if any, include violations perpetrated against a minority group likely due to a lack of awareness among law enforcement agencies that has resulted in weak rule of law.

Similarly, Article 156 of the Criminal Code has largely been used to prosecute those accused of blasphemy, particularly against Islam, with Amnesty International Indonesia recording 61 such cases that occurred between 2017 and 2020.

By contrast, the Racial Discrimination Law - the only law that specifically targets racism, has only been used to prosecute a handful of people, several of whom are themselves members of minority groups, as in the case of Veronica Koman and that of ethnic-Chinese politician Bobby Jayanto, who was accused to have called non-Chinese Indonesians 'black-skinned', although his case was later dropped. National Human Rights Commission member Choirul Anam said in an online discussion last year that there has yet to be a single conviction under the law.

The uneven implementation of these laws, coupled with the less overt everyday racist and ethnic discrimination faced by minority groups cast a spotlight on how far Indonesia still has to go before in can be truly said to have achieved Bhinneka Tunggal Ika.

Usman Hamid (usman.hamid@amnesty.id) is the Director of Amnesty International Indonesia.