Limitations have long defined Indonesia’s modern theatre, so the pandemic could not stop progress

Indonesian version

Ibed Surgana Yuga

Near the end of 2016, in a performance with the Kalanari Theatre Movement, I suggested that epidemics stimulate the creation of a (new) language for humanity. An epidemic is a time when people are more aware of life; when they sharpen their instincts for survival and continue to defend life. All human creative energy is directed to maintaining life: science, technology, philosophy, religion, and also language. An epidemic introduces a new order, and a (new) language provides a way for people to face up to and live with the situation.

In the performance itself none of this explanation was stated explicitly, but instead was woven into the structure and text of the performance. Indeed, the performance, which was staged for the Salihara Community, didn’t use words, but a language of bodily movement and sound. It was based on a hypothesis about the origin of human language. Various threads of the history and human knowledge around language and its creation were woven into a site-specific performance which moved from place to place together with the audience.

Kalanari Theatre and I have indeed often explored site specific theatre since the group formed in 2012 in Yogyakarta. At first we used the site specific format simply as a strategy to deal with a lack of funding to hire a theatre building and other performance facilities. Then we got used to struggling with, rehearsing and staging shows in spaces not intended for performances: rice fields, gardens, parks, brick factories, back yards, unfinished houses, old cinemas from colonial times, and so on. Struggling with spaces like these led us to create a new concept of theatre which we still maintain today: ‘becoming intimate with a space’. In the process we questioned again the connections between a performance and a space, between a performance and its surroundings, as well as its links with the audience and society.

Questioning the meaning of these ties was the first step in the development of Kalanari as a theatre entity. Our view of theatre shifted from one of artistic production to that of a cultural movement. We used theatre as a doorway into and at the same time an exit from various cultural movements. Our original platform was simply production of performances, then we added discussion as a vehicle for production and consumption of knowledge, rehearsals and workshops as a space to create awareness of links between the body, theatre and daily life, and collaboration as a space for dialogue linking theatre to spaces outside theatre, including literary creation and publishing.

Living with limitations

Last year we began a program that we planned to continue for some time: researching and performing the history of Indonesian theatre at various stages. This program began by questioning how to perform the history of something that has existed for a long, long time. A direction for the research and a process of presenting it on stage had just been planned when the pandemic hit. For Kalanari, as an institution run by volunteers, postponement of a program of this kind was something quite normal – part of the process of engaging in dialogue with limitations of time, space and funding.

This sense of normality arose from our awareness that to perform modern theatre in Indonesia is a decision to accept living with limitations. The long history of this theatre tradition shows us that limitation is its natural state, shaped by many factors, including government regimes, financial support, technology, social norms, religion, and even the dynamics of the theatre world itself. In this situation creative activities are efforts to create greater breadth, or a search for possibilities to move within the established boundaries.

When all physical meetings have to be curtailed during a pandemic, space becomes still narrower on one hand, but on the other is extended online. As an institution we decided to continue some of our work, individually or in small groups. A number of Kalanari members gathered online to create a digital broadcast. Others worked with outside groups, applying creative strategies they had previously employed with Kalanari. I myself, stranded in my home neighbourhood in Bali from the beginning of the pandemic, used this time as an opportunity to take apart and open up again various programs and ideas that had been laid aside for several years.

As an artist, I myself do not have, or perhaps don’t yet have, a taste for creating digital works. For example, I’ve never been particularly interested in making films. I’m still not sure why. When so many performing artists are trying out various ways of presenting plays on digital platforms during the pandemic, experimenting with new ways of interacting with the public, I myself have returned to the classic path, written works. At the beginning of this article, I discussed the pandemic representing an impetus for the creation of a new language. While other artists have been preoccupied with online performances, I have been contemplating the fact that written works can circulate freely at this time. This classic creation of literature is a path almost unaffected by the pandemic. So, my own creative energies are currently focused on written theatre.

A theatre literature movement

For several years Kalanari has been publishing books in the theatre field under the name Kalabuku. Kalabuku is operated as a movement in theatre and performance literacy based on concern about a scarcity of books on this subject. This occurs because major publishers are reluctant to publish books likely to attract a small number of readers and a very small profit margin. Kalabuku has been operating since 2017 (although I’ve been using this name since 2011 to publish collections of my own plays) on a voluntary, not-for-profit basis. Working like this is one way we can keep active in an environment full of limitations. Up until now Kalabuku has published 15 books consisting of plays and discussions of theatre by Indonesian writers such as Afrizal Malna and Benny Yohanes, as well as translations of works by Chekhov, Tolstoy, Dario Fo and Lajos Egri.

Because it runs on a voluntary basis Kalabuku isn’t able to engage professional workers. I edit and take care of the visual design of the books, while artist friends from Kalanari help with operational matters. The year 2020 has been a very productive one. Early in the year, when the pandemic began, we published a small book by Afrizal Malna, Pertumbuhan atas Meja Makan (Things grow on a Dining Table.) This is a play produced by the group Teater Sae at the beginning of the 1990s, a landmark in the resistance by Indonesian theatre to the New Order regime.

After that most of my time was spent editing the translation of a classic book about theatre by Lajos Egri, The Art of Dramatic Writing. Although a conventional classic I regard this book as very important for Indonesian theatre, especially for playwriting. In the many decades that modern Indonesian theatre has been performed not a single book in Indonesian has comprehensively addressed the art of writing plays. A few conference papers, lectures, essays and articles have appeared, but all of these have been narrow in scope with a limited circulation. We published Anasatia Sundarela’s translation of Lajos Egri’s work in mid-2020.

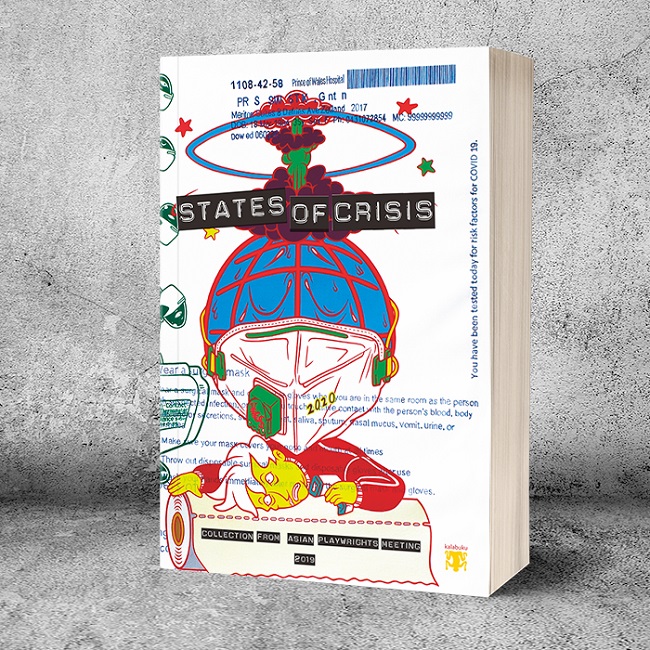

In July, working with the Indonesian Dramatic Reading Festival (IDRF), Kalabuku published State of Crisis, a collection of six plays presented at the 2019 Asian Playwrights Meeting in Yogyakarta. This was the first English-language book published by Kalabuku. It contained contemporary plays by young writers from Thailand, the Philippines, Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia and Japan.

LeLakon 2020: A debut mid-pandemic

The highlight of my work during the pandemic has been LeLakon, a platform for curating Indonesian plays with the aim of collecting, documenting and disseminating plays by Indonesian theatre artists and writers. The plays were collected through an open call, curated by a team of curators, then published in the form of an anthology. LeLakon 2020 was the work of Kalabuku and Kalanari working together with the Indonesian Dramatic Reading Forum (IDRF), Kala Theatre in Makassar, and the Bandung Performing Arts Forum.

LeLakon represented the realisation of an aspiration I had been forced to postpone for many years. The idea arose from my disappointment with various Indonesian playwriting competitions which involved announcing winners and awarding prizes, but didn’t go on to publishing the winning entries and allowing the public to access them. These limited competitions produced the name and title of these works but not the plays themselves, which were supposedly their focus.

I thought a pandemic would be a good moment to launch a platform for play curation. But how could would we finance it while the economy was in chaos? What reward could we provide to the writers whose plays were chosen? How could we compensate curators and other workers for their efforts? How would we fund production of the books?

These questions were gradually answered as discussions began with a number of theatre artists and activists. Four of them agreed to work together voluntarily as curators. They were Muhammad Abe (actor, translator, director of IDRF, based in Yogyakarta), Shinta Febriany (director, poet, playwright, Makassar), Brigitta Isabella (arts critic and researcher, Yogyakarta) and Riyadhus Shalihin (director, dramaturg, playwright, Bandung). The institutions where these people worked were also prepared to support LeLakon.

But what kind of reward could we give to the writers whose plays were chosen for publication? When LeLakon was launched at the beginning of August as an open call for Indonesian plays, the announcement read ‘LeLakon is not a competition, there are no prizes for winning entries. Instead each writer of a play which is selected for publication will receive five copies of the anthology and the right to share the profits of its sales.’ At first, we were pessimistic about the likelihood of writers sending us their work, because the winners of playwriting competitions usually receive a minimum of 5 million rupiah.

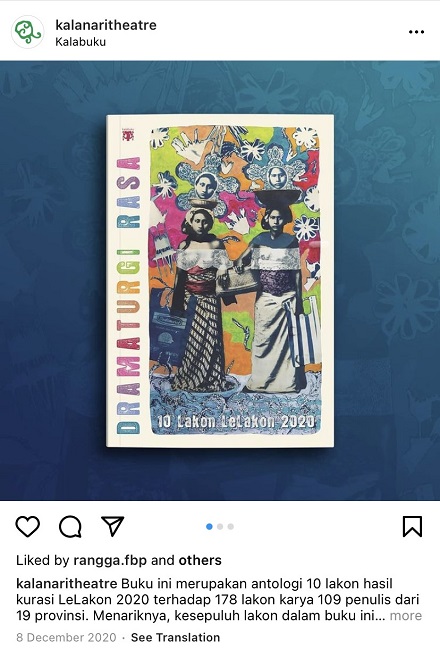

When the time arrived, we were very surprised to receive 178 plays from 109 writers in 19 provinces. Choosing ten from 178 plays of very diverse types was not an easy task, especially since there were no fixed criteria, just the subjective criteria of the individual curators. The selection took place in two stages. The first stage, based on the personal choices of individual curators, produced 27 plays. The second stage consisted of online meetings of the curators aimed at reducing the number of plays selected from 27 to 10. Here various criteria emerged to be discussed and investigated.

Because our platform is not a competition the quality of a play was not the only criterion for selection. The region where the writer lived was one point considered, because we wanted the book to be a space where readers could learn about different regions. Another important criterion was the gender of the writer and how the issue of gender was treated in the play. Special consideration was given to plays presenting a perspective of gender which was not patriarchal or hyper masculine.

The 10 plays selected were: Bis Malam (Night Bus) by the Kaleng Merah Jambu Collective in Purwokerto), Cinta dalam Sepotong Tahu (Love in a Slice of Tofu) by Agnes Christina in Yogyakarta, Elliot by Dyah Ayu Setyorini in Sidoarjo, Jangkar Babu Sangkar Madu (A Maidservant’s Anchor, a Bird cage of Honey) by Verry Handayani and friends in Yogyakarta, Lidah (Tongue) by Luna Vidya in Makassar, Manufaktur Anatomi Kera (Manufacturing the Anatomy of a Monkey) by Gulang Satriya Pangarso in Bandung, Mata Air Mata (Eyes of Tears) by Bambang Prihadi in Jakarta, Nuning Bacok (Nuning Stabs) by Andy Sri Wahyudi in Yogyakarta, Perempuan dan Panci Nasi (The Woman and the Pot of Rice) by Nurul Inayah in Makassar, and Rarudan by Wayan Sumahardika, Bali.

The anthology, Dramaturgy of Feeling, was published in mid-December 2020 without any financial support other than the profits from Kalabuku’s previous book sales. This is the way we keep Kalabuku alive.

We plan to produce LeLakon periodically in order to publish more plays by Indonesian writers. It is gratifying and encouraging that LeLakon has been able to make its debut during a pandemic and managed purely by volunteers. In the midst of the economic hardships of this time, the loss of opportunities for artists to make a living, and the fear of being overrun by the virus, a cultural movement of this kind can still be carried out enthusiastically, by volunteers, with the aim of extending discussion and knowledge of theatre through literary creation.

Ibed Surgana Yuga (ibed_sy@yahoo.com) is a director and playwright with the Kalanari Theatre Movement and the editor of Kalabuku. Several of his plays are published in the collections Perbuatan Serong (Yogyakarta, 2011), Di Luar 5 Orang Aktor (Yogyakarta, 2013), 10 Lakon Teater Indonesia 2017 (Jakarta, 2017) and in translation in New Indonesian Plays (London, 2019) and States of Crisis (Yogyakarta, 2020). Instagram: @kalnaritheatre; @kalabuku_ Twitter: @kalanari