Ron Witton

It may come as a surprise to some that there are Malay-speaking communities spread across the globe. Ronit Ricci’s book Banishment and Belonging: Exile and Diaspora in Sarandib, Lanka and Ceylon is a fascinating study of one of these communities, the Malay-speakers of Sri Lanka. It is a study of their history as a community born of exile from their native lands of present-day Indonesia and Malaysia.

Before discussing the book, it is useful to survey the many places in the world where exiled Malay-speakers have similarly maintained their language and religion. The term ‘Malay’ has generally been used to refer to those who came from present-day Indonesia and Malaysia. My own awareness of the Malay diaspora dates from 1962, when I enrolled to study Indonesian and Malay Studies at Sydney University. I was taught by Hedwig Emanuels, a charismatic Indonesian lecturer who was largely responsible for the flowering of Indonesian studies in Sydney in the 1960s. In one of his first lectures, he explained that he was of Javanese ethnicity but was born in Suriname, on the northern coast of South America, home to a large community of Malay and Javanese speakers. Pak Emanuels had a Dutch name because he had been adopted by a Dutch family. Suriname was formerly Dutch Guiana, which was held by the Netherlands from 1667 until it gained independence in 1975. Some 14 per cent of Suriname’s population of just over half a million are descendants of Javanese contract workers who had been transported there in the 19th century by the Dutch colonial government to work in the cane fields.

I travelled to Indonesia at the end of my first year, which helped my Indonesian fluency immensely. Then, during my second year of studies, I became friends with an Indonesian-speaking student at the university and learned that she had been born in Noumea, the capital of the French colony of New Caledonia, which lies in the Pacific to the northeast of Queensland. She invited me to visit her family for the summer university vacation. As I was studying both Indonesian and French this seemed an excellent way of improving both languages while also having another international adventure. To my delight, I learned that her family ran an Indonesian restaurant in Noumea and that I would be living at the back of the restaurant with her family. Moreover, their family was of Javanese descent and her father was a dalang, or puppeteer, who regularly put on all-night performances of Javanese wayang, or shadow puppets.

From 1896 until Indonesian’s independence, nearly 20,000 Javanese were brought to Noumea under an arrangement between the Dutch and French colonial governments, to work as contract labourers in the coffee plantations and nickel mines. As was the case with Suriname, their descendants have continued to speak Javanese and Malay. Needless to say, my stay greatly helped both my Indonesian fluency and appreciation of Indonesian cuisine and culture.

In later years I visited Holland where one cannot but be aware of the large proportion of the population who are of Indonesian descent. The forebears of many families arrived in Holland during the 350 years of colonial rule, but a majority are descendants of the 300,000 Indonesians who left the former Dutch East Indies after Indonesia’s protracted independence struggle from 1945 to 1949. A large number of these came from eastern Indonesia and had been supporters of the failed Republic of South Maluku. The Dutch population of Indonesian descent have now lived in the Netherlands for generations and number more than a million, many of whom have maintained their language and customs.

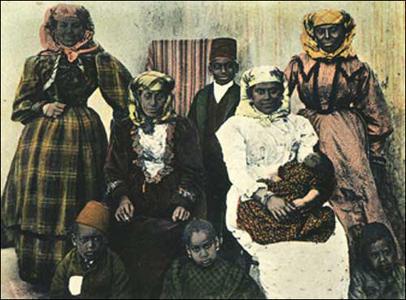

Another longstanding community of Indonesian speakers born of exile and banishment are the ‘Cape Malays’ of South Africa. The Dutch held the Cape of Good Hope as a colony from 1641 to 1824. Because it was an important fuelling station en route to Batavia and the lucrative spice islands, the Cape colony was administered from Batavia, the administrative capital of the Dutch East Indies. The Cape’s population was originally constituted by Dutch colonial officers who brought native troops from all over the Dutch East Indies. They were soon augmented by large number of slaves, political prisoners and exiles from the colony. It is estimated that there are now about 166,000 people in Cape Town who are referred to as Cape Malays, with a further 10,000 living in Johannesburg. Many have kept their Islamic beliefs and speak Cape Malay.

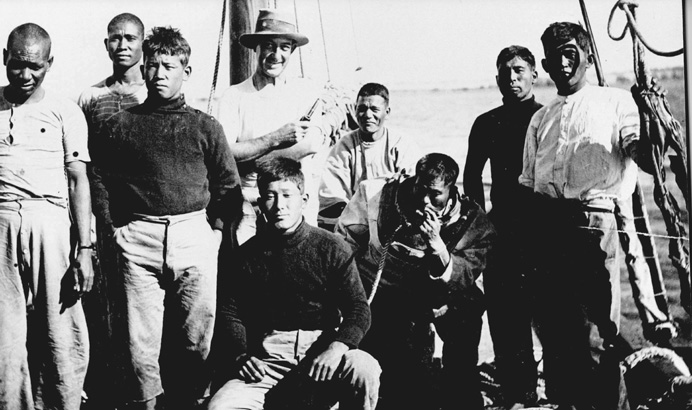

Surprisingly Australia is also home to a small but longstanding Malay-speaking community. While colonial Queensland brought Javanese indentured labourers to work in the cane fields, most of them returned to Java upon Federation in 1901 when the White Australia Policy became federal law. For hundreds of years before that, however, Buginese sailors from Sulawesi (in what is now Indonesia) had been spending time on Australia’s northern coast where they fished for trepang, or sea slugs, for the Chinese trade. This trade ended with the White Australia Policy whereupon the Buginese returned to Indonesia, in some cases taking with them Aboriginal wives whose descendants can still be found in southern Sulawesi.

Since the late 1800s, many ‘Malays’ had been working in north western Australia as pearl divers. Many of those working in the pearl trade came from the island of Timor and were referred to as ‘Koepangers’, derived from the old Dutch spelling of Kupang, the major town on Timor. A considerable number of these divers and sailors, vital to the pearl industry, managed to stay on after Federation and their descendants can still be found in places such as Broome and Darwin. There are still a number of old Muslim graves with names in Arabic (Jawi) script in cemeteries across northern Australia.

However, by far the largest ‘Malay’ community in Australia is to be found on the Cocos (Keeling) Islands off the Western Australian coast. Of the islands’ population of approximately 550, 75 per cent are Islamic, the majority of whom speak Malay rather than English as a first language. They are the descendants of indentured workers brought there from the Dutch East Indies and Malaya by John Clunies-Ross who in 1886 had been granted the islands ‘in perpetuity’ by Queen Victoria. The territory was incorporated into Australia in 1955. There is also a sizable Malay-speaking community on nearby Christmas Island, which lies quite close to Indonesia and is today the site of one of Australia’s controversial refugee detention centres. Around 2010 I visited the detention centre several times as a member of the Refugee Review Tribunal and enjoyed speaking Indonesian in shops and offices, as ‘Malay’ is widely spoken. Malay has official status as a local language and hence government notices and printed material are in both English and Malay. Some of the islands’ descendants have also moved to Western Australian coastal towns including Port Headland where some 10 per cent of the population speak Malay and maintain their customs and religion.

In Cuba where there is a small Indonesian community made up of former Indonesian students who were studying in the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc in 1965. They were, generally wrongly, assumed to be communists by the Indonesian New Order government and their citizenship was cancelled and so they could not return home. A number of such exiled Indonesians gravitated to Cuba and were allowed to settle there. After their Indonesian citizenship was restored by President Abdurrahman Wahid (Gus Dur) in 1999 some returned to Indonesia for a visit. However, one returning exile told me, he found Indonesia at that time, with rampant capitalism, virulent social media and an elite flaunting their wealth, so disconcerting that he decided he preferred the simple life of Cuba. These exiles found that present-day Cuba, with its vintage cars, lack of internet and social equality resembled the simple Indonesia they had left in the early sixties, and was much more to their liking. Moreover, they so appreciated Cuba’s excellent education system and universal health care that some of them had arranged for family members to come and join them.

Sri Lanka and Malay culture

On another trip overseas, this time to Sri Lanka, I made contact with another vibrant minority community made up of descendants from the Malay archipelago, and this at last brings us to the book under review. All these long-neglected overseas Indonesian/Malay communities deserve to be studied, and Professor Ricci has set a high standard for such an undertaking. Using old Malay and Javanese texts from Sri Lanka, including babad [chronicles], hikayat [prose stories], pantun [four-lined poems] and syair [traditional verse], she has chronicled what life was like there over the centuries and how these exiles remembered their homeland. Ricci has also investigated the way their existence was known and written about in old texts in Java and beyond. However, the central theme of Ricci’s book is that the Malay community came to Sri Lanka because they were forced to, either because of banishment or because of the system of exploitative contract labour that resulted in their ending up as exiles from their homeland.

Professor Ricci begins her book by stating:

Beginning in the late seventeenth century and throughout the eighteenth, the Dutch United East India Company (VOC) used the island of Ceylon as a site of banishment for those considered rebels in the regions under Company control in the Indonesian Archipelago, many of whom were members of royal lineages. Convicts and slaves from these territories were also sent to Ceylon, as were native troops who served in the Company’s army. After their takeover of the island in 1796, the British, too, brought to Ceylon colonial subjects from the archipelago and the Malay Peninsula, primarily to serve in their military. It is from these early political exiles and the accompanying retinues, soldiers, servants, convicts and slaves that the community of the Sri Lankan Malays developed, with its cohesiveness based, above all, on an ongoing adherence to the Muslim faith and the Malay language.

She explains that the term ‘Malay’ was generally used to refer to all those who came from the Malay/Indonesian archipelago, but that they and their descendants often spoke their own regional languages such as Javanese, Sundanese or Balinese. It is often her linguistic insights that make this study so fascinating; this is demonstrated in the title to her book, which lists the variety of names for Sri Lanka (Sarandib, Lanka and Ceylon), each of which reflect the book’s theme of banishment and exile.

Sri Lanka was known to the Muslim world as Sarandib, the place on earth to which Adam was banished from heaven. As an aside, one should note that, somewhat peculiarly, it is from the word Sarandib that in 1754 Horace Walpole, the English writer, coined the word ‘serendipity’. The island of Sarandib was long known to Muslims in the Indonesian and Malay Archipelago both through the Quran’s description of the banishment of Adam, and as a place through which many travelled on pilgrimage to Mecca from the Malay world. Indeed, it was recorded that in the late-19th century, Malay was the second-largest language grouping after Arabic, spoken in Mecca.

Sarandib, the Arabic name of the island, is cognate with Sielen Diva, the Greek name for Sri Lanka. From the word Sielen many European forms were derived, including the English name for the island: Ceylon.

Sri Lanka was known as Lanka in the Hindu world. In the epic poem the Ramayana, Lanka is the place to which Sita is abducted by Ravana, the king of Lanka, and from where Rama comes to rescue her with the help of Hanuman and his army of monkeys. These monkeys built a bridge of stones from India’s Coromandel Coast, the remnants of which remain in the form of the string of islands linking Sri Lanka to India. This tale, told through many mediums, including wayang, dance, and stone reliefs on temples, was central to the folklore of Java, Bali and other parts of the Hinduised Malay world.

In the Dutch East Indies, banishment and exile to Sri Lanka was a vital part of a colonial strategy to destroy local feudal and chiefly rule, in order to gain territorial control. Thus, today’s Sri Lankan community is made up of diverse backgrounds, with many having Javanese or east Indonesian ancestry. A portion of the political exiles in the late-17th century, and especially throughout the 18th century, were members of ruling families in their homelands. Examples documented by Professor Ricci include Sheikh Yusuf of Makassar, a leader, religious scholar and ‘saint’ from Sulawesi in 1684; the Javanese king Amangkurat III of Mataram along with his retinue in 1708; Sultan Fakhruddin, the twenty-sixth king of Gowa in south Sulawesi in 1767; the prince of Bantam; the crown prince of Tidore; and the king of Kupang. Such prominent figures had followers who joined them in exile and often also established a local following in Sri Lanka.

Some of the banished eventually returned to their places of origin but many stayed and lived out their lives in Ceylon, either by choice or deprived of any alternative. These early arrivals from the archipelago to Ceylon come from different islands and regions and, as a consequence, spoke multiple tongues. As Ricci notes:

Their religious affiliation was also not monolithic, as can be glimpsed occasionally in archival records. A Dutch document from 1691, for example, noted that ‘widows of Amboin soldiers would be provided with small pensions provided they are Christians.’ There is evidence that certain exiles, convicts or soldiers, accepted Christianity and that some later reverted to Islam. The references to Balinese and Ambonese soldiers in Dutch service, although not explicitly discussing religion, suggest that there were Hindus and Christians among the larger group.

The Dutch had taken control over Sri Lanka from the Portuguese in 1517 and held it until its conquest by the British in 1796. After they took over Sri Lanka, the British brought over many Malays from the Malay states to form the historic ‘Malay Regiment’. For many years the Regiment helped the British both to maintain control of the island and to serve their interests throughout their empire. There was a further intake from the Indonesian archipelago between 1811 to 1816 when Raffles administered the Dutch East Indies after its takeover by Britain. These newly recruited soldiers joined existing members of the Malay Regiment. Hence the ‘Malay Regiment,’ like the term ‘Malay’ itself, included descendants from the Malay Peninsula and the Indonesian archipelago, often coming from the islands of Java, Sumbawa, Madura, Bali and Ambon, and also ethnic groupings such as the Bugis and Batak.

Later, under the British, many Malay speakers came as contract labourers to work on coffee and other plantations, and through force of circumstances never returned home.

Exilic legacies

It should be remembered that exile and banishment was always a constant threat for those living under colonial rule, and ‘transportation’ was the quintessential British form of exilic punishment. For example, a ‘Malay’ soldier, Drum-Major Oodeen, who deserted from the British forces in 1803, was captured, tried for treason and sentenced to death in 1815, only to have his sentence commuted to transportation to New South Wales. He later served the NSW colonial government under the name of John O’Dean and was used as an interpreter in the short-lived settlement of Fort Wellington on Australia’s north coast. Another example is that of Ajoup, a 22-year-old convict, described as ‘of the Malay faith’, who arrived in Sydney in 1837 having been sentenced in Cape Town, South Africa, to 14 years’ transportation.

The continuing and flourishing use of Malay in Sri Lanka is evidenced by the fact that in 1869 Colombo became the site of the first Malay-language newspaper in the world: the Alamat Langkapuri. Ricci discusses its significance thus:

... alamat meaning ‘sign’, ‘signal,’, ‘indication of things to come’ and, most pertinently, ‘news.’ The newspaper appeared fortnightly and was written in Malay using the gundul [Arabic or Jawi] script, making it accessible – at least theoretically – to a broad readership beyond Ceylon’s borders in British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies. Disseminating international as well as local news, promoting Malay poetry, experimenting with advertising techniques and inviting its readership to connect with each other and the broader communities by way of letters and an early version of editorial opinions, the Alamat Langkapuri possessed transformative potential. Yet despite the keen interest in the Malay community’s religious affairs expressed throughout its pages, as well as the consistent reporting on matters having to do with British rule of the island, neither the name Sarandib – echoing with Islamic tradition and identity – nor the name Ceylon with its contemporary relevance was selected for the newspaper’s title. Rather, it was Langkapuri: That choice, and the excerpt of a letter published in the newspaper, testify to the ongoing relevance of Ramayana imagery among the Malays.

The Alamat Langkapuri was later joined by a second newspaper, the Wajah Selong [Views of Ceylon].

Of particular interest in Ricci’s study is the evidence she found of an awareness in the Dutch East Indies of the existence of Sri Lanka and the threat of exile to there. Indeed, the old Malay word disailankan and its Javanese form diselongaké [to be sent to Ceylon] was a verb used for ‘banishment’. In Lombok there is Gunung Selong (Mt Selong) which is a corruption of the word ‘Ceylon’. Gunung Srandil, near Cilacap on central Java’s southern coast, bears the Javanised form of the name Sarandib. Recalling Adam’s fall through its name and topography, it is a site of spiritual and religious importance where many perform pilgrimages. Nearby Gunung Selok, which may well be a misrepresentation of Selong, is also a site of Javanese ascetic practices associated with foundational figures of the Mataram lineage, many of whose members were exiled to Sri Lanka. A similar older verb, ngekap [to be sent to the Cape], recalls an earlier period when the Cape of Good Hope served as a similar place of colonial banishment from the Dutch East Indies.

In Sri Lanka there is much evidence of the languages of the earlier exiles and of the absorption of their descendants into the Malay Regiment. As Ricci outlines, in Sri Lanka the Javanese were generally referred to as ‘Ja’:

In Colombo one comes across Jawatte (‘Ja Compound’) Road, Jawatte Street, Jawatte Mosque and Jawatte cemetery, as well as signs that declare the presence of Malay Street (Figure 9.2), the Malay Cricket Club and Sri Lanka Malay Association, the latter two located at the compound known as Padang (‘field,’ referring to the playing field where cricket matches took place). Perhaps most evocative... is the old, whitewashed building of the Malay Military Mosque standing on the small, winding Java Lane. Mosques known locally as ‘the Malay Mosque’ were erected in towns across Ceylon, often in the context of regimental life, including in Badulla, Kurunegala, Kandy, Trincomalee and Hambantota. The mosque in Kinniya, on the island’s northeast shore, boasts a trilingual sign asserting its resonant name: ‘The Jawa Jummah Mosque’.

Ronit Ricci has set a high standard for others to follow in documenting the experience of Indonesians and Malay-speakers who found themselves banished from their homeland, and exiled to the far corners of the world.

Ronit Ricci, Banishment and Belonging: Exile and Diaspora in Sarandib, Lanka and Ceylon, Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Ron Witton (rwitton44@gmail.com) gained his BA and MA in Indonesian and Malayan Studies from the University of Sydney and his Ph.D. from Cornell University. He has worked as an academic in Australia and Indonesia and now practises as an Indonesia and Malay translator and interpreter.