There is an urgent need for institutional support to better understand and treat depression

Versi Bh. Indonesia

There is an urgent need for institutional support to better understand and treat depression

Aliza J. Hunt

Bu Mariasih stood awkwardly in the doorway, her body hunched, folding inwards on itself as though she desperately wanted to disappear. Her eyes, ringed by fatigue, were unfocused, staring out beyond the bustling scene of women preparing for the day’s celebration. The 13-year-old son of Pak Dukuh (the head of the hamlet) was being circumcised! Tens of women who were crammed into the outdoor cooking area were stoking the fires under two enormous woks of boiling oil. Others were washing, sorting, and slicing great piles of green vegetables and cuts of horse meat, while children gleefully clutched long strings of fried intestine.

One of the women inquired gently as to whether Bu Mariasih and her family had eaten breakfast. Extra portions of the choice sweetmeat (fried intestine) were doled out to her two children and another woman ushered her over to where she could assist with the preparation the kangkung or water spinach. Bu Mariasih, like many Indonesians I interviewed three years after the 2006 Yogyakarta earthquake, was suffering from depression. And like many others, Bu Mariasih had not sought or received any treatment.

A blueprint for care

When I conducted my research in 2009, in Bu Mariasih’s district in the Yogyakarta area mental health care facilities and mental health professionals were non-existent. By 2014, the blueprint for a comprehensive mental health care system was provided by the 2014 Mental Health Law, which included building mental health infrastructure and training personnel at all levels of the healthcare system. Supported by the national health insurance program (Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional (JKN)) and implementing body Badan Penyelenggara Jaminan Sosial Kesehatan (BPJS) , this blueprint mapped out universal access pathways for mental health care provision beginning with the primary healthcare centre (puskesmas), through to secondary care clinics and wards in hospitals and mental hospitals. Once discharged, patients (whose treatment is paid by the state), would receive ongoing outpatient treatment through the program jiwa or mental health program at the puskesmas.

Although implementation has been slow, today Bu Mariasih’s district has a puskesmas equipped with a mental health program and a resident psychologist. Similar districts in the Yogyakarta area have lay mental health outreach workers (kader kesehatan jiwa) to help people in need find appropriate treatment. Many local physicians and nurses at both primary and secondary care levels have received specialist mental health training. Many districts in the Yogyakarta area now have impressive mental health infrastructure and personnel. One might therefore expect that the Bu Mariasihs of today would finding treatment at the local puskesmas. This, however, does not appear to be the case.

In the six months leading up to the passing of the Mental Health Law, a puskesmas in an area not too far from Bu Mariasih’s village recorded over one thousand visits from patients suffering from anxiety-related illnesses and almost seven hundred visits from people who were diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. Interestingly, depression was not diagnosed by the puskesmas physician (no psychologist was working at the facility at that time) in all of 2014 or 2015, and only four patients with depression were seen in 2013.

In the course of the research I made similar observations about another three puskemas in Yogyakarta. I interviewed resident psychologists who worked in these primary health care centres. I concluded that very few individuals with depression were seen at the primary health care level. A psychiatrist explained to me that although diagnoses of depression in the puskesmas in the Gunung Kidul regency of Yogyakarta were low (as they seemed to be in other areas), prescriptions of antidepressant medications were increasing, suggesting that they were either used in treating anxiety disorders and/or somatic expressions of psychological distress, such as pain or gastrointestinal upsets. She said that it could also indicate a hesitancy to diagnose depressive illnesses; a diagnosis dilemma.

My research into depression in Indonesia included 27 interviews with mental health specialists across primary, secondary and tertiary care institutions. I interviewed psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers and specialists in psychosomatic medicine in Yogyakarta and Jakarta. Although anxiety and somatic-type distress were seen more often in primary health care settings, my research indicated that depressed patients tended to consult psychiatrists at private practices or clinical psychologists working in hospitals. At first glance, it appeared that women like Bu Mariasih waited until their symptoms had become very severe before they would seek medical care. In the meantime, they may seek the assistance of local healers.

As I continued questioning the mental health professionals, it became clear that they employed two distinct modes of understanding and diagnosing depression. The first group, whom I name the Textualists, applied the Indonesian diagnostic formula from the Pedoman dan Penggolongan Diagnosis Gangguan Jiwa (PPDGJ-III, the Indonesia Diagnostic Manual of Mental Disorders) rigidly. If their patients displayed at least two of three primary symptoms of depression (depressive affect, anhedonia and fatigue) and at least two additional symptoms from the full symptom list (including decreased concentration, lack of self-worth, feelings of guilt and uselessness, pessimism, self-harm, suicidal ideation, disturbed sleep, and/or loss of appetite) most of the time during the last two weeks, they would be diagnosed as having a depressive episode.

The second group, whom I named the Contextualists, indicated that the absence of a specific psychological vocabulary among Javanese patients, combined with a strong social stigma surrounding mental illness, resulted in presentations of what one of my informants called ‘Masked Depression’. Masked or Endogenous Depression were popular terms in ‘western’ psychiatry in the 1970s and 1980s, declining towards the end of the twentieth century. Masked Depression occurs when other behavioural or somatic symptoms masked, in the opinion of a mental health professional, an underlying affective disorder. As my informants explained, it was only after several visits that the more typical symptoms of depression emerged. Consequently, a whole raft of presenting complaints could be interpreted as depression. Bu Mariasih’s diagnosis would therefore vary depending on the type of clinician she saw and how she presented her symptoms. For example, she might have felt more comfortable telling the doctor that she worried so much about paying her children’s school fees that it made her stomach ache, as opposed to talking about her depressed mood.

The lack of consensus among Indonesian mental health professionals complicates our understanding of depression in Indonesia and fails to reliably locate the Bu Mariasihs of the present within the mental health care system. Is she depressed? Is she anxious? Does she have a medically explained (or unexplained) somatic or physical problem instead? If she is depressed, why does she typically enter the mental health care system at the secondary and not primary care level? Or if she does go to the puskesmas, why is she presenting more socially acceptable anxiety and somatic complaints, which lead her to be diagnosed with something other than depression? These questions, and many others, hang uncomfortably in the air when we start to talk about depression in Indonesia.

Local context, global condition

Depression is recognised worldwide as a leading cause of disability with an economic cost in the hundreds of billions of dollars. There is a clear need for countries like Indonesia to develop a context-specific evidence base for understanding and treating depression. This requires demonstrating an urgent need and institutional support.

Yet, the term ‘depression’ is unknown to most Indonesians. Neither is there a consensus around the definition of depression amongst the expert class, who tend to know more about statistically rare disorders, including the psychoses. The literature on depression that does exist in Indonesia focuses primarily on epidemiological estimates of the prevalence of depression. Fortunately, some recent work explores Javanese experiences of depression. In 2018, Widiana and colleagues developed an Indonesian Checklist for Depression based on a Javanese sample. Their research produced a robust measure of Indonesian depression with universal depression symptoms identified within five indigenous symptom clusters. These included physical symptoms, affect, cognition, social engagement and religiosity.

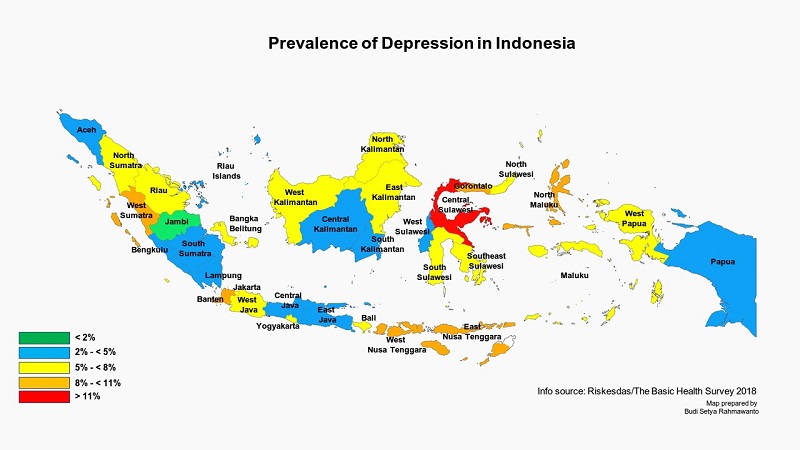

The most recent and reliable estimate of the prevalence of depression in Indonesia comes from the Riskesdas Basic Health Survey published in 2018. It suggests that 6.1 per cent of a population representative sample or over 163,000 Indonesians are suffering from depression, as opposed to 9.8 per cent of the same sample who are suffering from more generalised emotional distress (this number includes those suffering from depression, anxiety, and other related disorders). Independent of how prospective patients present themselves to clinicians, the prevalence of depression symptoms among Indonesians is consistent with global averages.

So far depression has not received the institutional attention it deserves, both within mental health professional organisations and the Indonesian bureaucracy. Historically, psychotic patients and those with substance abuse disorders have had greater visibility both in research and in the public eye. These disorders have been at the centre of human rights issues – around forcible restraint (pasung) and polarising policies on illicit drugs. As a result, even after the flurry of regulations and guidelines on mental health following the 2014 Mental Health Law, depression and other common mental disorders rarely appear in health policy.

The agency responsible for mental health in Indonesia, the Mental Health and Addiction Sub-Directorate of the Ministry of Health, has a restrictive annual budget of around less than one per cent of the total health budget. The limited Indonesian evidence base, a divided expert class and low visibility in public policy have failed to attract much additional spending. Clearly this argument is circular. We need a developed evidence base on depression in Indonesia to unite the expert classes and to provide tailored treatments to the hundreds of thousands of Indonesians who are suffering. However, until depression is given more of a priority on the agendas of both central governments and professional organisations, it will do little more than languish as an underutilised, poorly understood, and insufficiently indigenised term borrowed from ‘western’ psychiatry.

Aliza Hunt (aliza.hunt@anu.edu.au) is associated with the Australian National University. Her current research focuses on depression in the elderly in Indonesia.