Dick van der Meij

Within months of its publication in November 2002, Peter Carey’s masterpiece, The Power of Prophecy: Prince Dipanegara and the end of an old order in Java, 1785-1755 (Leiden, KITLV Press) was in its second edition. This is no small thing for a scholarly work of almost one thousand pages.

The book sits in the libraries of anyone interested in Diponegoro, the Java War, and Java’s history in the 19th century and also on the shelves of the members of Diponegoro’s trah, or lineage group. It offers a picture not only of the prince and his role in the Java War, but of Java and its socio-economic-religious situation in the Dutch colony of the Netherlands East Indies at the time and earlier. Carey’s study is also available in an Indonesian version entitled Kuasa Ramalan: Pangeran Diponegoro dan Akhir Tatanan Lama di Jawa, 1785-1855 published by KPG in 2012 and reprinted in 2012 and 2016.

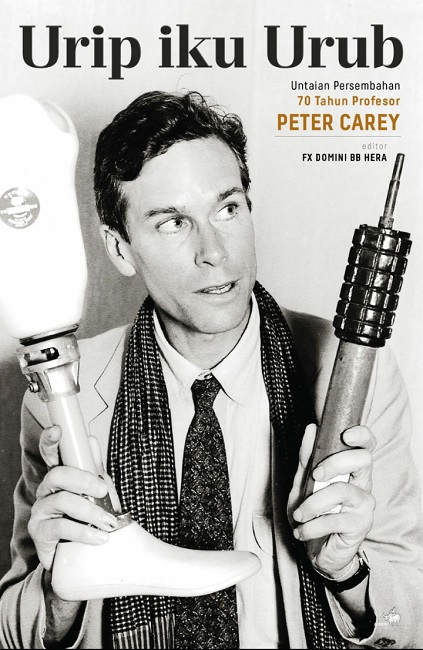

The overwhelming attention given to the story of Prince Diponegoro through these publications and Carey’s advocacy, ultimately led to the inscription of the Babad Diponegoro (Autobiographical Chronicle of Diponegoro) in the registry of UNESCO’s Memory of the World program in 2013. The history of this inscription is related by Wardiman Djojonegoro in Chapter 5 of the festschrift dedicated to Peter Carey, Urip iku Urub: Untaian Persembahan 70 Tahuh Profesor Peter Carey. If anybody has put 19th century Java on the map of world history it is Peter Carey.

Yet, as the festschrift makes clear, Peter Carey’s historical scholarship is only one aspect of his life’s work. As co-founder of The Cambodia Trust (1989-2014) he was instrumental in helping the people in Cambodia and later also in Sri Lanka and elsewhere in Southeast Asia, recover from the nightmare of war by providing artificial limbs to amputees. Carey’s work in Cambodia was recognised by Queen Elizabeth II and he was made a Member of the British Empire in 2011.

A life's work

The festschrift begins with a foreword by another non-Indonesian giant of the study of Java, Merle Ricklefs, Peter Carey’s friend and colleague. Ricklefs sets the tone for the book by positing that the human factor in scholarly work is perhaps just as important as the outcome of the research itself. As can be gleaned from Peter Carey’s short autobiography (Chapter 1), in order to understand a person’s scholarly contribution it is indeed helpful to know something of his personal life, his background and motivations in approaching his work.

Chapter Two describes how the book came into being and how, contrary to the views of some higher up the academic ladder, the editor was able to bring the festschrift together to shine a light on Peter Carey’s significant contribution to Indonesian historiography. The publication of Urip iku Urub met with some resistance largely because it was believed strange that someone in Malang, East Java should attempt such a book, whilst in Oxford where Carey taught Asian history for 35 years, such a publication was never attempted.

The book is divided into five parts. Part One, ‘Peter Carey dalam Refleksi’ (Peter Carey in Reflection) deals with the broader topics of history-writing and its use and misuse and Carey’s role in present-day historical scholarship. Contributors include Peter Carey himself, Simon Head, Wardiman Djojonegoro, Catrini Kubontubuh and Ki Roni Sodewo. Part Two, ‘Perang Jawa Sumber Inspirasi Kreasi Seni’ (The Java War as Source of Inspiration for Artistic Creation) reflects on the way Carey’s attention to and books about Diponegoro have inspired people in Java to create new forms of performing arts based on Diponegoro’s life. Articles by Werner Kraus, Aji Prasetyo and Subi in this section highlight the importance of Indonesian translations of foreign scholarly work on Indonesia.

Part Three, ‘Tatanan Lama Jawa’ (Java’s Old Order) deals with Java as is was before the Java War and features articles by Sri Margana, Kuncoro Hadi, Hendrik E. Niemeijer, Lilie Suratminto, and Daya Negri Wijaya. Part Four focuses on the five years of the Java War and its impacts. It includes articles by Bondan Kanumoyoso, Ahmad Athoillah, and Herman Joebagio. Part Five includes articles that discuss some aspects of the aftermath of the Java War and of the Old Order in Java by Didi Kwartanada, Sri Ratna Saktimulya, Daradjadi, Sudibyo, Martina Safitry and Eka Ningtyas.

The book contains no less than 119 illustrations many of them photographs of Peter Carey in the various stages of his life and other illustrations including, of course, Diponegoro.

The book is well edited and a joy to read. It discusses various aspects of Java’s history in relation to Peter Carey’s academic work. It is also important that the book stresses Peter Carey’s other academic and social activities, which reminds us that scholars have interests and compassion outside the confines of the scholarly world. The festschrift has been put together with obvious affection for its subject. The Javanese title of the book also emphasises the human element - Urip iku Urub (Life is light) the light of humanity and passion – and is therefore well chosen.

FX Domini BB Hera (Ed.), Urip iku Urub: Untaian Persembahan 70 Tahuh Profesor Peter Carey, Jakarta: PT Kompas Media Nusantara, 2019.

Dick van der Meij is the director of Indonesian Manuscript and Text Services and an expert on Indonesian manuscripts. He is currently affiliated with DREAMSEA, Digital Repository of Endangered and Affected Manuscripts in Southeast Asia. His latest book is Indonesian Manuscripts from the Islands of Java, Madura, Bali and Lombok which was published with Brill in Leiden in 2017.