Versi Bh. Indonesia

Diego Garcia Rodriguez

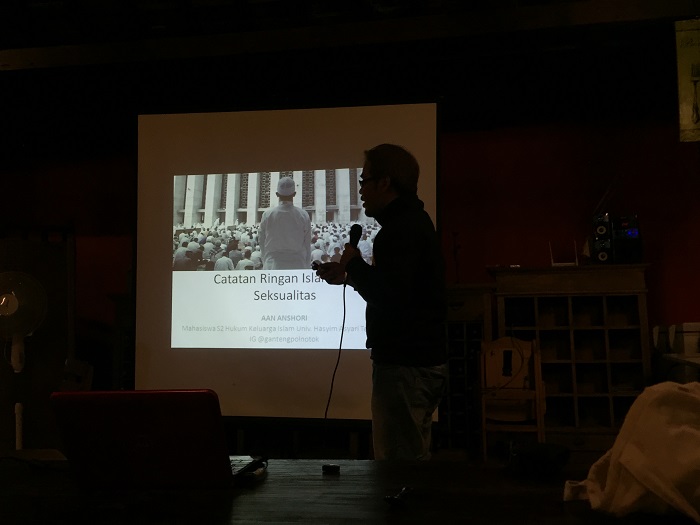

It’s Thursday night in Yogyakarta, late September 2018. A civil society group has been organising an event on sexuality and Islam, spearheaded by LGBT ally and activist Aan Anshori. At the last minute we receive a WhatsApp message that the venue has changed due to safety concerns. We drive 30 minutes until we reach the new location. We turn our phones to airplane mode and double check the GPS is off. We are told to not post pictures online until the talk finishes. We cannot tell anyone we are here. The event starts. The speaker begins his presentation, titled ‘Catatan Ringan Islam dan Seksualitas’ (Light Notes on Islam and Sexuality).

These days, one can only attend such discussions and gatherings by invitation. According to data from the Wahid Foundation and the Indonesia Survey Institute (LSI), in 2016 the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community was one of the most hated groups in Indonesia. By 2018, they were the second most hated behind communists. Despite the worrying nature of these statistics, LGBT Indonesians and their allies are working actively to effect change, fighting for their rights to be accepted as Indonesian citizens.

Western media depictions of LGBT Indonesians as victims of their own religion and culture perpetuate orientalist stereotypes by essentialising Islam and Indonesian society as conservative and homophobic. Indonesian media frequently portrays LGBT people as paedophiles, carriers of disease, and/or sinners.

Through exploring the actions of LGBT allies in Java, we can obtain an alternative picture that contests such representations. During a year of fieldwork between 2017 and 2018, I encountered that beyond the homophobic declarations of government officials and conservative actors, other voices have supported LGBT rights, often based on religious interpretations.

In today’s Indonesia, a large number of LGBT and non-LGBT activists work together to promote tolerance and inclusion.

Promoting tolerance

In the last few years, Muslim figures like Aan Anshori, Kyai Hussein Muhammad and Abdul Muiz Ghazali have participated in events to promote LGBT inclusion within Islam. Their role is significant considering their work as religious leaders and scholars. They work with LGBT-rights NGOs to produce stories of pro-queer acceptance. This acceptance is promoted by developing contextual interpretations of religious sources and thus challenging the literal way texts are often interpreted. An example of contextual interpretation are the workshops organised by the NGO GAYa Nusantara which bring together religious leaders from a variety of faiths (Buddhists, Christians, Muslims).

As one NGO activist explained to me, ‘This is not a conversation that was this important for us in the past; the focus was rather on sexual health and HIV/AIDS, but we have slowly increased our discussions about religion, gender and sexuality, working together with religious figures.’ While prior to the so-called 2016 ‘anti-LGBT crackdown’ there were a few forums and discussions on these issues, activities have intensified.

During 2017 and 2018 I attended several events where LGBT-rights activists gathered with religious leaders and members of NGOs working on inter-faith dialogue, gender and sexuality, such as the Youth Interfaith Forum on Sexuality (YIFoS). YIFoS is encouraging important discussions through its ListeningYou program, a series of encounters that took place in 2018. The sessions put together individuals working at organisations such as LBHI (Lembaga Bantuan Hukum Indonesia, or Indonesia Legal Aid Institution), GAYa Nusantara and the Institute for Criminal Justice Reform with religious leaders like the Christian pastor Stephen Suleeman from Jakarta’s Theological Seminary (STT). They were organised around key issues: SOGIESC (sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, and sex characteristics), human rights, LGBT and criminalisation in Indonesia, religion and sexuality, and LGBT discussions in the media.

In one session, the leader of YIFoS and Stephen Suleeman presented LGBT-inclusive interpretations of religious sources, the former focusing on Islam and the latter on Christianity. This was done by introducing some of the most controversial Qur’anic verses and presenting the multiple meanings that the Arabic text could have to illustrate their multiple possible interpretations. While the leader of YIFoS presented these ideas, the attendees also had the chance to ask questions and seek clarification. One participant, a gay Muslim man, shared with the audience that it was difficult for him to accept himself as gay and Muslim since he felt his religion was against his sexual orientation. The rest of the audience reacted to his intervention with applause, some of them hugging him to express their support. The speaker replied that Islam is not against homosexuality and turned to the religious sources to develop her statement.

Sharing stories about being LGBT and Muslim creates a sense of belonging. Another attendee, a self-identified Catholic transpuan (transgender woman), shared her story of transition and narrated her past life as a priest. Some of the participants had never encountered progressive readings of the stories of Lut or Sodom and Gomorra contesting conservative interpretations. Even though not everyone knew each other prior to the event, sharing a common space and acquiring new ideas together was perceived by some of the participants as a source of self-recognition. The feeling of community among religious audience members, some of whom felt abandoned by their religion mostly because of the heteronormative dominant interpretations, also increased their interest in joining future sessions to learn more about progressive religious exegesis, some participants asking about future events in question time.

GAYa Nusantara

Progressive religious allies of various faiths have engaged with NGOs to produce written outcomes. These projects, illustrating the collaborative work of progressive religious allies and queer-rights NGOs, do not only take place unidirectionally from the religious leaders to the members of those organisations. The queer activists have also started building projects for the mainstreaming of gender and sexual diversity to faith communities. As Dede Oetomo, founder of GAYa Nusantara, explains, the mainstreaming of SOGIESC discourses to religious leaders in East Java started in 2017.

The work of GAYa Nusantara has focused mostly in the cities of Surabaya, Mojokerto, Jombang and Malang through three main objectives: firstly, the dissemination of knowledge about gender and sexual diversity among religious people, both leaders and communities. Second, bringing together religious groups and LGBT individuals to get to know each other. Lastly, expanding the acceptance of LGBT people on various levels, especially among those who are members of religious communities.

In order to reach these objectives, GAYa Nusantara has created a steering committee composed of queer religious individuals and faith leaders. This has been done following a process of identification and networking with local faith leaders through face-to-face conversations. Public seminars have taken place in Islamic universities such as Universitas Hasyim Asy’ari in Tebuireng, in Jombang; Universitas Islam Malang and IAI Uluwiyah in Mojokerto; and the Christian church of Merisi in Surabaya.

GAYa Nusantara has also organised gender and sexuality short courses with young queer religious individuals and members of faith communities to share their lived experiences of religion and have held discussions on religious texts. In this process, social media campaigns using written materials, videos and memes on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube have been key tools to spread their message. The example of GAYa Nusantara illustrates a two-directional process emerging both from LGBT allies and LGBT-rights activists with the goal of spreading messages of tolerance through education on religion, faith and spirituality. In addition to this, the work of Aan Anshori and Musdah Mulia is available online offering alternative interpretations of the Islamic sources that are LGBT-friendly.

Without being too loud, LGBT-rights activists and their allies are working hard across Indonesia to promote their rights by making use of religion. While dominant discussions often represent religion in conflict with sexual minorities, these activities illustrate the potential of contextual religious interpretations for the building of LGBT agency. More than that, they illustrate that there exists an alternative to conservatism that is built through dialogue and LGBT-friendly religious materials.

Diego Garcia Rodriguez (diego.rodriguez.16@ucl.ac.uk) is a PhD candidate in Gender and Sexuality Studies at University College London working on gender, sexuality and Islam in Indonesia.