Versi Bh. Indonesia

Monika Winarnita, Nasya Bahfen, Gavin Height, Joanne Byrne & Adriana Rahajeng Mintarsih

Even before the #MeToo movement, Indonesian gender equality activists were using online campaigns to encourage women to speak up about sexual assault and harassment. In April 2016, Lentera Sintas Indonesia (a support group for survivors of sexual violence) and online feminist magazine Magdalene launched a multi-platform education campaign about sexual violence. Along with promoting online discussion using the hashtags #MulaiBicara (start talking) and #TalkAboutIt, Lentera Sintas Indonesia and its partners held panel events and film screenings.

Initially created by African American woman Tarana Burke in 2007, the #MeToo movement became widespread in October 2017 in response to alleged assault and harassment by Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein. It quickly developed into a global social movement and many women around the world have since taken to social media to raise awareness of sexual violence and gendered power imbalances. While the #MulaiBicara discussions preceded #MeToo, Magdalene co-founder and managing editor Hera Diani notes that in the wake of the global movement the publication is now receiving more submissions dealing with sexual violence.

Feminism in Indonesia is not a new phenomenon, with gender-based activism occurring even during the final days of the New Order regime. For instance, SIP (Suara Ibu Peduli or the Voice of Concerned Mothers) initially formed to express concerns over the inflated price of infant formula milk, and later embraced campaigning against the collusion, nepotism and corruption of the New Order regime with a feminist political agenda, including organising street demonstrations. Indeed, SIP lobbied the new post-Suharto government to investigate the rape and sexual assault of Chinese Indonesian women during the May 1998 riots.

Two decades later, the 2018 Women’s March in Jakarta – led by the Jakarta Feminist Discussion Group – attracted up to four thousand people (up from 2017’s inaugural march of several hundred demonstrators). Since its creation in 2014, this Facebook group has grown to 2000 members and its activities expanded beyond the realm of online discussion. The march, along with smaller parallel marches outside of Jakarta, encompassed a collection of causes, including LGBT issues, domestic and migrant worker rights, child marriage and reproductive rights. Responding positively to the marches via social media, President Joko Widodo congratulated the protesters, declaring that Indonesia needs ‘strong women,’ though he stopped short of commenting on specific issues. Although no backlash or support from other politicians was found online, in response to Widodo’s actions negative memes about him circulated via Twitter as part of a wider campaign in the lead up to the 2019 elections.

This progression from online discussion to offline action is important for Hera, co-founder of Magdalene and its managing editor, who explains, ‘social media activism can only do so much.’

‘It has to be combined with real activism in the field.’

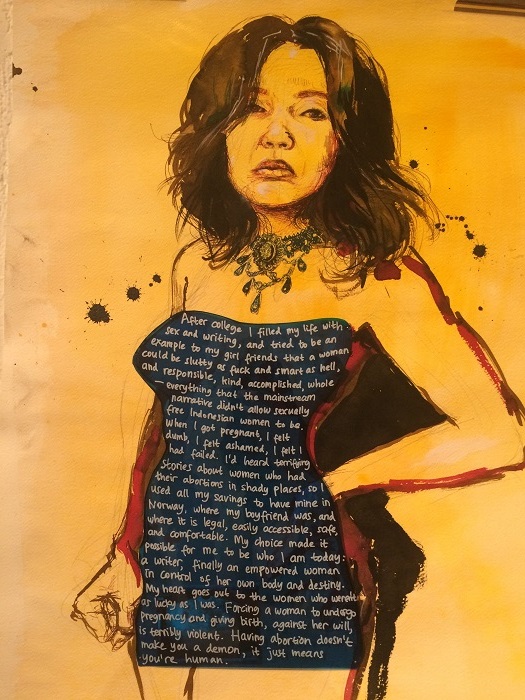

One such example of offline activism, House of the Unsilenced brought together sexual assault survivors and artists ‘to create new works about survivors’ lives’. The art project included workshops, panel discussions, performances and exhibitions in Jakarta, along with an online presence, from 21 July to 2 September 2018. The subjects explored by the project were wide-ranging, including the media’s treatment of sexual abuse cases, body shaming, sexual abuse within the family, Islamic perspectives on violence against women, and a lack of access to safe abortion being akin to sexual violence.

The project’s primary media partner was Magdalene, but Harper’s Bazaar Indonesia and The Jakarta Post also picked up the story. While the Jakarta Post article did touch on the serious issues with which House of the Unsilenced dealt, the others, as with most mainstream reporting of sexual violence in Indonesia, only provided a general overview of the event. Discussing sexual violence seriously and in-depth is still taboo in mainstream Indonesian media.

The House of the Unsilenced workshops involved around 50 survivors working with more than 30 artists (such as writers, visual artists, performance artists and musicians) to find ways to express the survivors’ stories in their own voices. The project’s creator, author Eliza Vitri Handayani, says that ‘telling these stories is a form of fighting.’

‘This is how we can help open the public’s eye about the nature of sexual violence and the impact, and what it costs the survivors to actually come and speak up’.

Beyond sharing stories and creating artworks, Eliza says the project was about ‘creating a community that can support each other’.

While Eliza says the #MeToo movement inspired her to create the project, House of the Unsilenced seems a natural progression for her. Since 2015, Eliza has run InterSastra, an independent publishing effort giving marginalised voices a platform. In March 2017 (prior to #MeToo becoming viral), Eliza published an article in Magdalene detailing her own experiences, exposing inappropriate behaviour and the frequently imbalanced power dynamics between older men and younger women in Indonesian workplaces.

Eliza doesn’t think of herself as an activist, but when asked if her writing is activism she says, ‘I think we all have a role in creating a more equal society and we do what we can, and what I do is through writing and art’.

She thinks a key benefit of social media lies in private discussion groups on platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp. ‘Private groups are great and help people to be able to speak up.’

‘I’ve seen women who first started sharing or speaking up within these smaller, safer groups,’ she says.

‘They found the support and confidence they needed, and then they started creating something with other women in their local community.’

Online discussion leading to offline activism is a possible path to social change. Digital campaigns can be matched with real life lobbying. An online petition calling for reforming of Indonesia’s sexual violence laws was launched by Lentera Sintas Indonesia, and gained 100,000 signatures before being presented to parliament. The petition was the most public element of a concerted lobbying effort by a group of organisations under the #GerakBersama, or #JointMovement campaign, calling for the passage of the Elimination of Sexual Violence Bill. Drafted in 2016, the bill remains stalled in parliament because it has been misunderstood and feared as a bill that would promote Indonesia’s marginalised LBGT community. For example, according to media sources, the bill recognises the rights of LGBT people in domestic violence cases.

Online activism is not surprising considering Indonesians’ use of social media is the third fastest growing in the world. Social media platforms enable awareness-raising and the recruitment of new activists, and also facilitate offline action. However, while promoting House of the Unsilenced, Eliza found it difficult to reach those who may benefit the most.

‘Social media can give a false sense of comfort,’ she explains.

‘Because okay, a lot of people liked the post, but we were really trying to cut through class barriers and there are some people that would really benefit from this that aren’t on social media.’

Both Hera and Eliza seem to agree on the benefits and limitations of online platforms. While social media is great for sparking conversations and sharing knowledge, it doesn’t supplant activism in the field. If the growing numbers at the Jakarta women’s marches are any indication, the two forms of activism can complement and facilitate each other well.

Monika Winarnita (m.winarnita@latrobe.edu.au, @MonikaWinarnita) is a Lecturer in Indonesian Studies at Deakin University and is a current Honorary Research Fellow and Chief Investigator in projects funded by La Trobe University. Nasya Bahfen (n.bahfen@latrobe.edu.au) is a Senior Lecturer in Journalism Studies and Chief Investigator in projects funded by La Trobe University. Gavin Height (g.height@latrobe.edu.au, @gavinheight) is a Research Assistant with an Honours degree in Politics at La Trobe University. One of his research interests is Indonesia's national elections. Adriana Rahajeng (adriana.rahajeng@gmail.com, @a_rahajeng) is a Lecturer in the English Studies program at the Faculty of Humanities, University of Indonesia and a PhD candidate under the Fulbright scholarship program. Joanne Byrne (j.byrne@latrobe.edu.au, @Byrne_JC) is a PhD candidate and Graduate Researcher at the Department of Social Inquiry, La Trobe University.

Acknowledgement: This article is part of the findings from Monika Winarnita’s Humanities and Social Sciences Early Career Researcher grant; as well as Nasya Bahfen and Monika Winarnita’s Research Focus Area Transforming Human Societies seed funding grant from La Trobe University.