Versi Bh. Indonesia

Najmah, Sharyn Graham Davies & Sari Andajani

An ‘ibu rumah tangga’ (housewife) is an idealised position in Indonesia, one aspired to by many women. Even whilst in power, Indonesia’s only woman president, Megawati Sukarnoputri, said her chief occupation was still as an ibu rumah tangga, serving her husband and children before anyone else in the nation.

But the difficulty with idealising this position is that an ibu rumah tangga is always and only imagined to be a faithful wife and a doting mother. Given their assumed angelic nature, they are problematically considered immune from diseases such as HIV, which are thought to affect only ‘immoral’ people.

This idealised image of an ibu rumah tangga means they are never imagined to be married to adulterous drug-using men, nor considered to be adulterous drug users themselves. This idealisation means few HIV-awareness programs target them.

But the fantasy of ibu rumah tangga not contracting HIV has shattered. In fact, almost half of all new HIV cases in Indonesia are found amongst women of reproductive age, most of whom identify as ibu rumah tangga.

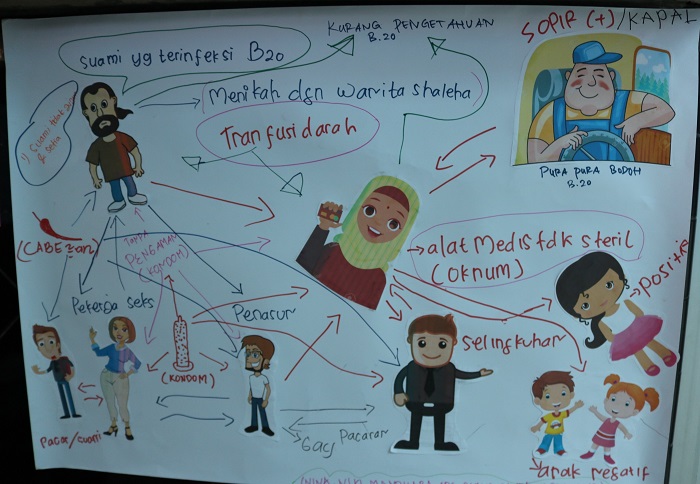

This group contracts HIV via various means, including blood transfusions, unsafe sex and intravenous drug use. A significant number of ibu rumah tangga, probably the majority, contract HIV from their husbands. This is how Ibu Bonita contracted HIV.

Ibu Bonita’s story

In 2009, at the age of 36, Ibu Bonita married a man name Pak Budi. This was Ibu Bonita’s second marriage, her first having ended in divorce a few years earlier. Within a year of marrying Pak Budi, Ibu Bonita gave birth to her first child, a daughter named Ani. While Ibu Bonita felt the marriage was a happy one, before their daughter’s second birthday Pak Budi became ill and was hospitalised. Doctors told Ibu Bonita that her husband had an infectious lung disease. At the end of 2011, within months of his hospitalisation, Pak Budi passed away.

As the families gathered to mourn, Pak Budi’s brother took Ibu Bonita aside and told her three startling things. First, he said that Ibu Bonita was in fact the fifth wife of Pak Budi, not the first and only one as Ibu Bonita had assumed. Second, he said that her daughter Ani was actually Pak Budi’s ninth child. Third, he told Ibu Bonita to get regular health check-ups. Ibu Bonita assumed her brother-in-law recommended regular check-ups just as a routine precaution. It was only later that she realised why her brother-in-law had been so insistent.

Ibu Bonita carried on life as best she could as a solo parent. But in 2013 she noticed she was getting increasingly ill and she didn’t know why. She was suffering frequent fevers and noticed fungal infections over her body, including in her mouth. She thought back to her husband’s illness, recalling similarities.

One day while watching television, Ibu Bonita saw a segment about a disease called HIV. When the symptoms were outlined, Ibu Bonita realised with horror that she likely had HIV. While hesitant to go to a clinic, she thought about her child and knew she had to get tested. Leaving her now almost four-year-old daughter with neighbours, she caught a public minivan to the Voluntary Counselling and Testing Centre she saw advertised at the end of the HIV television segment.

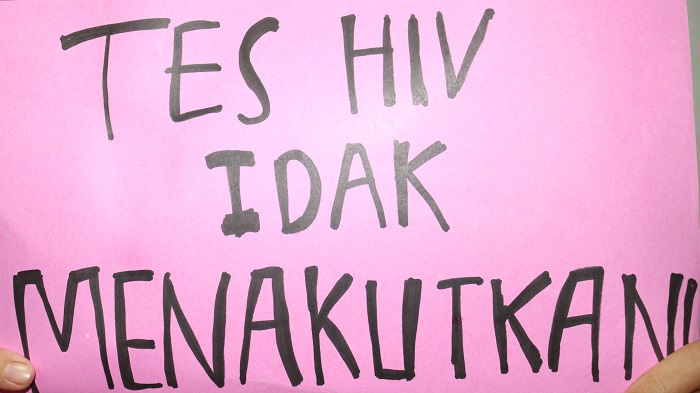

Entering the testing facility was daunting. Ibu Bonita worried someone she knew might see her enter or that someone who worked there might recognise her. But again, she focused on the wellbeing of her daughter and knew she had to be brave. Later, Ibu Bonita made a poster stating that ‘HIV tests are not scary’ to encourage other women to get tested.

The HIV test confirmed Ibu Bonita was HIV positive. She had an extremely low CD4 count. A CD4 count is a test measuring how many CD4 cells you have in your blood. CD4 cells are what help fight off disease and infection. A healthy person has between 500 and 1400 CD4 cells per cubic millimetre of blood. A CD4 count below 200 indicates serious immune damage and means that a person has developed AIDS, the end stage of HIV likely resulting in death if left untreated. Ibu Bonita had a CD4 count of 40, meaning she was seriously ill.

Doctors also tested Ibu Bonita’s daughter who thankfully was HIV negative. Ibu Bonita attributes Ani being HIV negative to her tahajud, or nightly prayers, during her pregnancy. The fact that Ani was delivered through caesarean section and was formula fed likely contributed to Ibu Bonita not passing HIV on to her daughter.

Ibu Bonita is certain she contracted HIV from her husband Pak Budi. She is not certain how he contracted HIV, but she thinks there are two likely ways: first, from his fourth wife who, it was rumored, was a sex worker, or second, through extramarital affairs. Pak Budi worked as a truck driver and was frequently away on long trips, staying overnight at truck stops. Ibu Bonita thinks it likely he was engaging sex workers. Ibu Bonita made another poster to show women various ways they can get infected with HIV (see main article image).

An idealised image

As an ibu rumah tangga, adamant that she has never had extramarital sex or used intravenous drugs, Ibu Bonita is exactly the type of person for whom contracting HIV is considered impossible in Indonesia. And yet she is living with HIV.

Imagining ibu rumah tangga as perfect angels who live in a perfectly angelic world does not stop them contracting HIV. Rather, such a fantasy merely serves to increase the risk of these women contracting HIV, passing HIV on to their children, and dying from HIV.

This idealised image increases risks for numerous reasons. First, if these women cannot imagine themselves contracting HIV, they will not get tested. And if society cannot imagine it, there will be little provision made for them to get tested, and little encouragement or demand that they do.

Second, if their contracting HIV seems impossible, there is no compulsion for unfaithful husbands to disclose their possible exposure to HIV; a wife’s morality is imagined as a good luck charm protecting her from her husband’s immorality. Compounding the problem is the fact that the idealised view of ibu rumah tangga encompasses the idea that they are sexually submissive, so even if a wife suspects her husband’s infidelity she cannot demand, or even suggest, that he use a condom.

Third, if ibu rumah tangga cannot be imagined contracting HIV, there is no imperative for those who know of a husband undertaking risky behavior, such as intravenous drug use or adultery, to tell the wife. Such disclosure may end the marriage and why risk that if people believe the wife will come to no harm.

The idealised view of ibu rumah tangga increases a mother’s risk of passing on HIV to their unborn children. If pregnant women do not know they have HIV, no provision will be made for caesarean births or formula feeding, both of which decrease the chance of mother-to-child HIV transmission.

The angelic image also increases women’s risk of dying from HIV. If a woman requests an HIV test, she is suggesting she has acted immorally; why would she need a test unless she has been unfaithful or used drugs? In order to save face, then, women may not get tested early and only find out too late that they have HIV. Further, if women do not disclose their status to family and friends but remain trying to live up to the impossible fantasy of an ibu rumah tangga, it is harder for women to access services and keep up with expensive medication regimes.

How then do we reduce HIV transmission and increase healthcare accessibility?

To reduce HIV transmission, everyone in Indonesia must acknowledge that ibu rumah tangga are at risk of HIV. If they are acknowledged as complex beings living in complex social worlds, awareness campaigns and treatments programs can target them. If women find out early that they have HIV they can start medication and implement practices to decrease their chance of transmitting HIV, especially to their offspring.

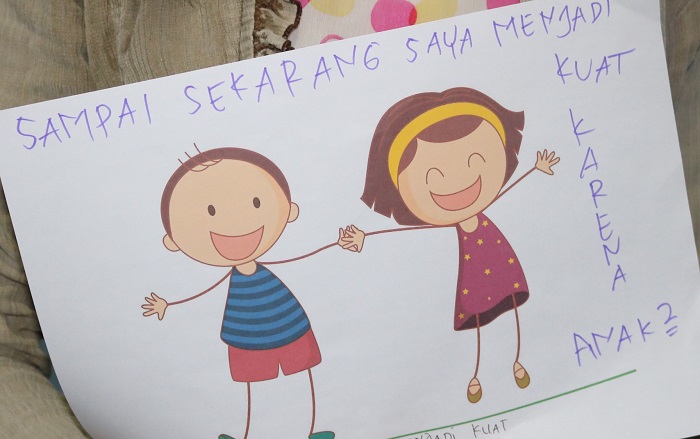

To increase healthcare access the stigma, shame and secrecy surrounding HIV must be lifted. Doing so will include demystifying ibu rumah tangga – seeing that they are not immune to HIV, but rather that they are human beings who can and do get HIV. Testing positive for HIV and accessing healthcare does not undermine a women’s role as a loving wife and mother. In fact it can increase their ability in this role by keeping them healthy. As Ibu Bonita’s poster shows, women find love and strength through continuing to be healthy mothers.

Imagining wives and mothers as immune to HIV is having deadly consequences. It is not impossible for wives and mothers to contract HIV. Acknowledging their risk, and empowering women to get tested and seek treatment will help curb HIV rates in Indonesia.

Imagine if when Ibu Bonita’s brother-in-law suggested she get regular health checks, he felt able to explicitly say, ‘Your husband has HIV. You must get tested’. Imagine if the doctors treating Ibu Bonita’s husband had informed Ibu Bonita that her husband had HIV and that she needed to get tested. Imagine if Ibu Bonita had been able to imagine that she, as a married monogamous woman, was at risk of HIV and demand a HIV test, and get early access to essential medication.

While Ibu Bonita survived despite the stigma, shame and secrecy surrounding HIV, the fate of many other women is not so positive.

Najmah (najem240783@gmail.com) is a PhD candidate at Auckland University of Technology and lecturer in the Department of Health at Sriwijaya University in Indonesia. Sharyn Davies (sharyn.davies@aut.ac.nz) is associate professor at Auckland University of Technology. Sari Andajani (sari.andajani@aut.ac.nz) is senior lecturer in the Faculty of Health at Auckland University of Technology.