Emily Rowe

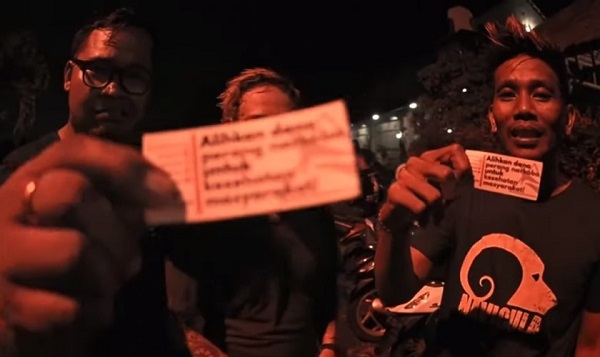

Earlier this year, Indonesian punk and grindcore bands went on a national tour to call for 10 per cent of government funding for drug-related law enforcement to be spent on health-led approaches. Ivan from the Bandung-based band Kontrasosial spread the message that ‘people who use drugs should not be put in prison. That is not a solution. It makes much more sense for money to go toward the health of society’.

The Indonesian government has set aside around US$25 million (A$37 million) per year to address the public health needs of people who use drugs. But it is spending more than five times as much on drug control measures that punish drug use. Very little is spent on harm reduction programs, such as clean needle programs and methadone treatment, which are known to save lives. The government’s approach to drug use is stoking the fire of a health and human rights crisis that is entirely avoidable.

An ongoing crisis

The Indonesian government has been relatively successful at keeping rates of HIV low, with less than one per cent of adults, or 620,000 people, estimated to be living with the virus. Sadly, this general success has not been replicated amongst those most vulnerable to HIV, such as people who inject drugs. Nearly one-in-three of these people are HIV-positive. This group requires a unique strategy to effectively prevent and treat HIV infection.

Foreign donors have bankrolled the much-needed prevention and treatment programs for decades. Until 2009, USAID and Australian Aid were the sole funders. Their programs were concentrated in cities and provinces with high numbers of people who inject drugs like heroin. But these days programs are dependent upon the Global Fund, which essentially serves as the piggy bank for addressing major epidemics in developing countries. As this international assistance will not continue in perpetuity, and the government appears in no hurry to step in, civil society organisations fear that the much-needed harm reduction programs will cease.

The Indonesian government can afford these prevention and treatment approaches, but instead chooses to spend its money on punitive drug control and a so-called ‘war on drugs’ , designed to punish people who use drugs – essentially waging war on an already stigmatised group of people. This zero-tolerance approach aims to dissuade the purchase, sale and use of illicit substances, but evidence indicates that these strategies have had little impact. In 2015, Indonesian President Joko Widodo ordered the execution of 14 prisoners convicted of drug-related offences. Since then, he has also rejected appeals for clemency from more than 64 others. This punitive approach has a heavy impact on women, as up to 90 per cent of the female population in Indonesian prisons are there for drug related crimes.

Lacking political will

The government has left harm reduction largely up to civil society. In place of funding health programs for people who use drugs, it instead pours resources into harsh law enforcement that criminalises, incarcerates and demonises drug users.

Since becoming president Joko Widodo has significantly strengthened the government’s leading drug control agency. During his first term he increased the budget allocation for the National Narcotics Agency (BNN, Badan Narkotika Nasional) by 94 per cent. He also gave the agency greater power, elevating it to ministerial level. Increasingly, BNN has used its clout to promote mandatory rehabilitation for users caught with small amounts of drugs. Even so, criminal sentencing for drug use remains the norm. Small-time, non-violent drug users overwhelmingly end up in prison, which has caused many Indonesian prisons to reach – and even exceed – full capacity.

Policy paper: Increasing public health funding to tackle drugs in Indonesia / Rumah Cemara

Some say that this punitive turn is the result of a knock-on effect from increasingly harsh policy responses to drug use in the region. President Joko Widodo has even said that he wants to emulate the war on drugs in the Philippines, telling police to shoot first and ask questions later. This might be just grandstanding to gain popular support. Regardless, this speaks to the government’s prioritisation of a punitive, criminal justice focused response as opposed to a public health and rights based one.

The Indonesian government does, however, invest substantially in opioid substitution therapies, such as methadone and buprenorphine. This helps to provide biomedically proven options for people and improve quality of life. But, alarmingly, no public money is used to support clean needle programs, which are proven to prevent the transmission of HIV and other blood borne viruses. Research has shown that for every dollar invested in needle programs, four dollars is returned in savings on healthcare. The programs save lives, and the Indonesian government’s oversight here has put the lives of drug users at risk.

A solution

The Indonesian government needs to step up its game, but it is not alone in the rank and file of other middle-income countries. Financial support for much-needed harm reduction programs is severely lacking across the board. There is an almost 90 per cent funding gap to fill.

Modelling by the NGO Harm Reduction International estimates that redirecting less than 10 per cent of the money spent on drug control in Indonesia (already US$100 billion) to harm reduction interventions would do the trick. In Indonesia, local NGO Rumah Cemara has been promoting this change, encouraging government stakeholders and donors to reassess budget allocations. Ten per cent of those funds spent on punitive and arguably arbitrary drug control would go a long way toward ensuring access to harm reduction programs for all people who use drugs. The HIV epidemic amongst people who inject drugs would be eliminated by 2030. And drug-related deaths would fall dramatically.

In order to make this a reality, the Indonesian government must acknowledge the evidence in support of harm reduction work, and increase its funding substantially.

Emily Rowe (Emily.Rowe@hri.global) is Asia Focal Point for the Sustainable Financing team at Harm Reduction International. She is also on the editorial board for Udayana University’s open-access journal: Public Health and Preventive Medicine Archive (PHPMA).