Living in the midst of uncertainty

Abdul Samad Haidari

As I sit down to write this, I look out upon a large crowd of refugees who have gathered outside the UNHCR building in Jakarta. They are pleading in desperation for their freedom, for a faster and transparent resettlement process, and for fairer humanitarian assistance.

Many elderly women and men, others with youthful faces, mothers cradling babies in their arms saying they have been asking for help for years on end, but feel they have been left here to rot.

They uniformly plead, ‘We want a fair process in resettlement without, leap-frogging, favoritism, gender and aged-based discrimination – we want food and shelters, medical assistance, accessibility to UNHCR in emergency situations while waiting to be resettled.’

An Afghan man, who has been stranded in Indonesia as a refugee for the last six years, said, ‘No one is here by choice; neither is anyone here to go to a specific country. We are not here against the UNHCR, IOM or the Indonesian government today, but rather to plea that they treat us as human beings. We find no meaning in life anymore.’

I have been living as a stateless refugee in Indonesia since 2014. For me and some 14,000 forgotten others, there is no clear fate ahead of us.

I am a member of the Hazara ethnic tribe from Afghanistan, where I was a journalist, a humanitarian aid worker and a volunteer teacher for refugee women. I fled because of my work reporting on terrorist groups, warlords, corruption and other radical groups in Afghanistan.

Like many others, when I dared to dream, my dreams were shattered. My books were burnt and my pen was broken when I attempted to write about on the ground realities. My childhood memories vanished under the feet of merciless self-declared rulers. And my school shoes remained by unknown hillsides, where I had to run for my life.

In fact, I have been running for my life since the age of seven. Being a Hazara and a religious minority in a conservative country like Afghanistan is to experience constant persecution. I have lived through civil wars – the sounds of rockets and missiles landing around my house is constantly in my mind. I remember living under siege without food or medicine; bullet holes peppered buildings and my favorite apricot trees were destroyed by bombs.

My people’s collective historical memory is stained with the brutal genocide that started in the 1880s under the despot ruler, Abdur Rahman, and continues to this day. 62 percent of our people are now gone as a result of systemic oppression and mass murder.

Stranded

In response to the ongoing protests and the massive refugee homelessness in Jakarta, a temporary shelter was opened in an abandoned military building in West Jakarta. However, the building has only 83 rooms and four toilets, and only has the capacity to accommodate 120 people – there are an estimated 1,700 refugees accommodated in this temporary camp.

Uncertainty still looms here – refugees do not know where they will head next. Many others remain homeless and plead for assistance in the streets in front of UNHCR in Jakarta and other cities across Indonesia.

What makes the situation so devastating for refugees and asylum seekers is waiting for a brutal number of years for resettlement. Some of us have been here since 2011. Their limit of endurance has been surpassed while living a life of nothingness. Refugees and asylum seekers in Indonesia are forbidden to work by law – without the right to put their skills and education to productive use.

Our movement is restricted. Access to education and health care is limited, and there is no emergency assistance. As a result, the physical and mental health of these cast-aside people is rapidly deteriorating.

Several refugees have committed suicide as a result of psychological pressure, and physical confinement. This has largely gone unreported in the official press.

Stuck for years in Indonesia, we all struggle to learn how to remain alive. I had to find a way to heal myself, and make use of these years.

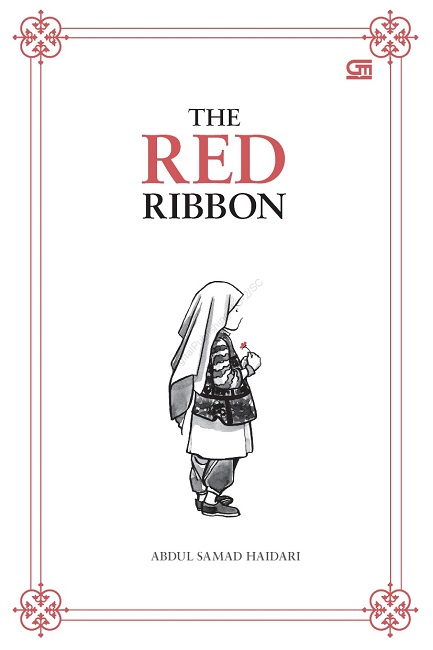

I started writing poetry. It took almost 5 years to complete my first book, The Red Ribbon. It is a form of autobiography in poetic form, a collection of works about a war-torn refugee’s survival. It contains the voices of refugees and shouts out a plea for a second chance for the stateless refugees to be allowed to live a free existence as human beings.

Refugees all have about them a feeling of war, it is what they fled in their home countries, where security was non-existent. They are ‘the left behind ones’, left in a state of helplessness and hopelessness with zero choice to build a life in Indonesia, or go to another country to start again, and with also zero choice to return to their home countries where they face death. This is a humanitarian disaster and a waste of talented lives.

Here the burden should not sit on the shoulders of UNHCR, IOM, or the Indonesian government alone. It requires a broader contribution from international organisations. It requires other countries to respond to this human suffering in a holistic way. This requires a more human rights-based approach. Countries like the United States, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Norway and Germany and other like-minded nations have felt a deeper sympathy for this human suffering of displacement across the world, but also need to redirect their hearts towards Indonesia’s refugees – their generosity is needed to increase their resettlement quotas, rather than providing aid only.

Hardline practices and policies only add to the suffering of war-torn people, who have already fled war and persecution. Refugees are not a threat, nor a virus and need to be granted the chance to more than just survival; they need a chance to thrive. This is about human rights, values, civilizational norms and human love. The current refugee crisis in Indonesia needs a more holistic approach – a more compassionate one perhaps.

Abdul Samad Haidari (abdulsamad.haidari96@gmail.com) is a 28-year old poet from Afghanistan who lives as a stateless refugee in Indonesia since 2014. He is the author of a poetry book ‘The Red Ribbon’. He is a former journalist from Afghanistan, a teacher, and a humanitarian aid worker. He was forced to flee Afghanistan three times on account of his journalism, his race and religious beliefs. He belongs to the minority Hazara ethnic tribe, which has been under persecution and slow-grinding genocide for centuries. He would like to acknowledge the support of Dr Ross Dunn in preparing this article.