A Dutch anthropologist lived in a Jakarta riverside slum to learn how residents there cope with constant flooding

Roanne van Voorst

In Bantaran Kali, owning a walkie-talkie is a symbol of high status. This is because the device can be used to collect information about possible floods in the neighbourhood. There is no formal warning system along the river banks. A few years ago, the government did pay for a loud speaker that was placed on the roof of the mosque, which was intended to sound the alarm if there was a flood coming. However, it turned out that the speaker was not waterproof, so during the next flood it broke down and has not been replaced.

But with a walkie-talkie, residents can communicate with the lock keepers who are located high in the hills above Jakarta. If the water there rises quickly there is a good chance that Bantaran Kali will be flooded a few hours later. Walkie-talkie owners use that information to bring their own belongings and family members to safety as quickly as possible; then they warn their neighbours.

In the middle of one night, after I had been living in Bantaran Kali for about two weeks, there was a loud banging on my door. I woke up startled and sat bolt upright. ‘Roanne,’ a man behind the door shouted. ‘Wake up, prepare, a flood is coming!’

My heart started to thump. I looked around in panic. A flood. That was to be expected, after all I had come here for that. And yet I had not thought at all about an emergency plan. I had no idea what to do, where to escape to. Until this moment I had been far too busy getting used to my new life in Bantaran Kali.

In addition, I always felt protected by the experience and knowledge of Aki. When I moved into the house, she actually still lived in the house, but she assured me she would move out soon.

‘Tomorrow,’ she said, ‘tomorrow I will have a new house, and you can live here alone.’

That turned out to be too optimistic, but after thirteen days busily getting organised the time had come. Aki would move upstairs, and I would be able to enjoy the privacy of my own house. I helped Aki empty the cupboard of her belongings, and brought them upstairs with her. Her television set hardly fitted – her new house was even smaller and more cramped than mine. At least I still had a corrugated iron roof that kept out the daily tropical rain; Aki only had an orange canvas sheet above her head in her new home.

‘But this is a better house than yours,’ Aki said when she saw that I was staring at her roofing with a somewhat worried expression. ‘I told you once before, and I’ll tell you again: just wait until it floods. Then you’ll regret the fact that you live in the fancy house on the ground floor, and you’ll be only too happy to come and camp under my roof.’

She would be right, and that happened rather quickly. On the first night I spent alone in my new house, I was awoken, not by Aki, but by loud banging on the front door.

BANG! BANG! BANG! ‘Roanne?’

I opened the mosquito net that I had hung up from the ceiling earlier that day – not to protect me from malaria or dengue, because the mosquitoes managed to find me anyway during the day, but to provide a reassuring shield between me and the many thumb-sized cockroaches. As quickly as I could, I put on a T-shirt and shorts and tried to decide what to take with me. My notebook with my notes, my laptop with my data, my camera. ‘Wallet, passport,’ I muttered out loud while filling a backpack with my most valuable belongings. Almost everything I had with me turned out to fit. I left only a few study books. Too heavy, I thought, not a good idea if I need to move quickly.

‘Roanne?’ This time it was a woman's voice. Aki did not wait for an answer, but had already swung open my front door. A locked door was out of the question – privacy was less important in Bantaran Kali than it was for me. Aki came in in her white nightgown. ‘The mattress must be lifted up,’ she said.

Earlier she had explained to me that she would hang her mattress from the ceiling during flooding. There were four screws in the ceiling for doing that, one of which I had used to hang up my mosquito net.

‘What is that you have hanging up there?’ Aki asked when she saw my mosquito net. She looked at it with a scowling face. ‘Do Dutch people think that is nice? We would rather hang paintings if we want to decorate our houses.’ She yawned deeply and gestured toward my toilet. ‘Pee first, then cook, then eat, then hang up the mattress,’ she instructed me.

‘And the rest of the stuff?’ I asked, ‘Shouldn't we evacuate right away? Is the water already outside?’

Aki emptied a bucket into the toilet bowl. She sleepily shook her head and began to wrap a cloth around my head. ‘Oh no,’ she said. ‘We still have time. The flood water will be here in five and a half hours. And it's a big one, so keep in mind that it will be flooded here for at least a week. Did they just tell you that? The men with the walkie-talkies? They always know everything.’ She tucked the last strand of hair behind my headscarf and scooped rice grains from a hessian bag into a measuring cup. ‘They know even the smallest details. They are a sort of flood soothsayer, and therefore they are the most important inhabitants of Bantaran Kali. More important than the kampung leader, more important than the village elders and certainly more important than that nonsense of a husband of mine. The men with the walkie-talkies know exactly when the river will overflow its banks and how long the water will stay and give us wet feet. Or rather: giveyou wet feet.’ Aki poured the rice from the measuring cup into a rice cooker and looked at me triumphantly. ‘Unless you come to shelter with me tonight and in the coming nights.’ She burst out laughing, throwing her head back.

No wonder Yusuf wanted to spend so much money on a walkie-talkie. He was the ninth resident in the neighbourhood to own one. The first proud owner – the then neighbourhood head – did not buy it himself, but got it from an official at the village administration. Along with the loudspeaker, which had been placed on top of the mosque, the walkie-talkie would serve as a flood warning system. ‘It took me weeks to understand how that device worked,’ the former neighbourhood leader told me later in an interview. ‘The official gave me an instruction manual, but I never went to school and can't read. I turned the knobs until I could hear voices amongst all the noise – then I could finally hear what the lock keepers were saying. But the reception was usually poor, and often I couldn’t understand what they were saying, so I just turned off the thing and set it aside.’

That was in the year 2000. Two years later, a huge flood came through the neighbourhood, and both the walkie-talkie and the speaker got wrecked. The neighbourhood head had not received a warning from the lock keepers; the reception had been so bad the day before that he had switched off the walkie-talkie again.

After that major flooding, government policy changed. There was a decision not to invest in warning systems for the flood-prone, illegal neighbourhoods along the river banks. Those areas were actually not intended for residential use at all, it was decided. According to the 2005 to 2030 Jakarta city plan, the riverbeds must remain empty, though vegetation may be grown there. So people just had to fend for themselves.

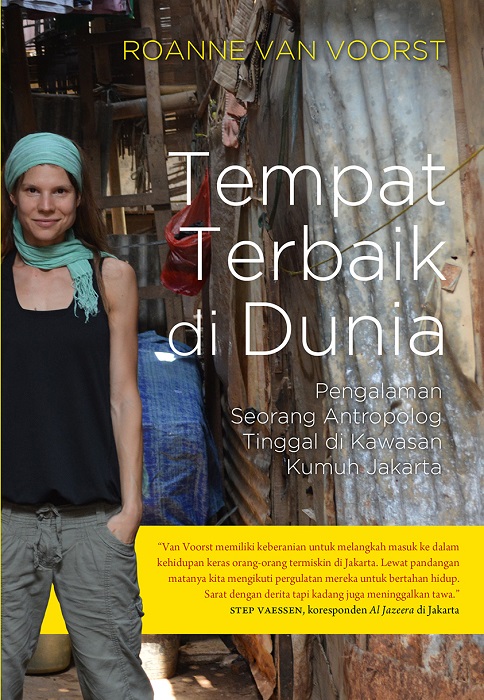

This is an extract from Roanne van Voorst’s book, De Beste Plek ter Wereld: Leven in de Sloppen van Jakarta [The Best Place in the World: Living in the Slums of Jakarta] (Amsterdam: Brandt, 2016). Translation by Helene van Klinken.

Also available in Indonesian as Tempat Terbaik di Dunia: Pengalaman Seorang Antropolog Tinggal di Kawasan Kumuh Jakarta (Tangerang Selatan: Marjin Kiri, 2018).

Roanne van Voorst (info@roannevanvoorst.com) is a postdoctoral researcher in the Netherlands. This book drew on her ethnographic research about poor people´s responses to flooding, ‘Get ready for the flood! Risk-handling styles in Jakarta, Indonesia.’ (PhD, University of Amsterdam, 2014).