In ancient Indonesian manuscripts, a disaster is sometimes not a disaster, but a message from the deity.

Wayan Jarrah Sastrawan

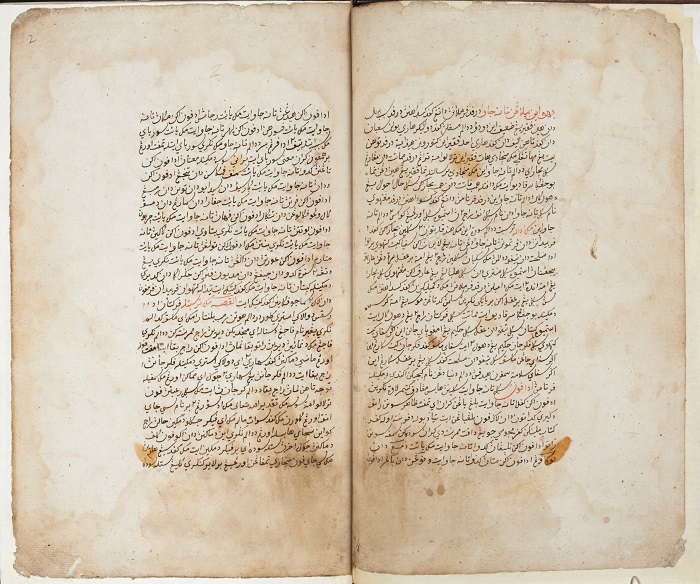

Throughout history, natural disasters have had a huge impact on the archipelago. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami that wiped out coastal communities on the west coast of Sumatra was just one of many extremely damaging occurrences. How have the region´s peoples responded to these life-changing events? The rich manuscript traditions of Java and Bali go back a thousand years. The conceptions of natural disasters we read there open a valuable window into how people have long talked about them.

The historical record

Perhaps the earliest surviving mention of a natural disaster in an Indonesian text is a Javanese inscription issued on 10 October 907. It concerns a village called Rukam that had been destroyed by volcanic flows. Javanese chroniclers normally focussed exclusively on royal politics. But they sometimes include natural disasters in their chronicles. They did this because disasters were considered to be intimately connected to the social realm, as will be discussed below.

Very few detailed descriptions of Indonesian natural disasters survive from before 1600. The historian Anthony Reid referred to European sources for seventeenth-century disasters in the archipelago. He found an account of a tsunami in 1674 by the Dutch-German naturalist Rumphius, as well as reports in the archives of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) of eruptions and earthquakes in Maluku throughout the seventeenth century. Reid suggested that a re-examination of the available sources, particular those in Dutch and in Javanese, could shed light on probable tsunami events in 1618 (southern Central Java) and 1660 (Aceh).

Destruction

All discourses on natural disasters highlight their destructive effect. Reid argued that seismic disasters – earthquakes, tsunamis and volcanic eruptions – have had a profound impact on the long-term course of Indonesian history. Periodic disasters checked population growth in the archipelago. As a result, population densities were lower there in the early modern period than in other world regions.

This damaging impact features prominently in local accounts. A description of an eruption of Mount Merapi in the Javanese history Babad Tanah Jawi, compiled in 1826, emphasises the unbearable noise it made.

There was a relentless shrieking in the air. It sounded as if the sky was being torn apart, like the whole mountain was thundering. Everything was in uproar. The mountain's fissures responded by cracking open. The crater growled. Ash rain fell, boulders and pebbles rolled down, volcanic mudslides flowed. They say there were many huge rocks, and lahar flowed down into the River Umpak.

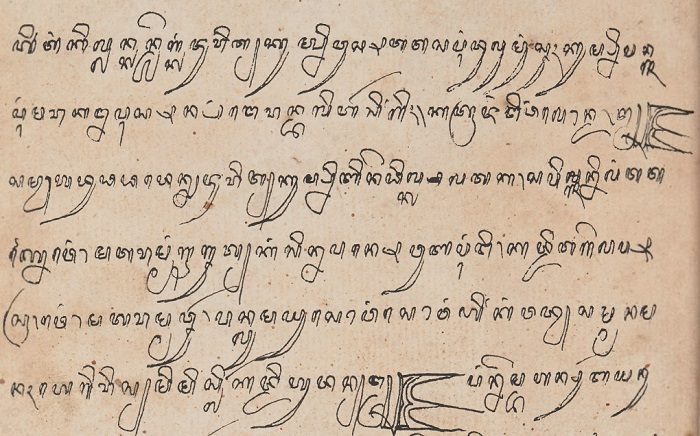

A Balinese chronicle called Babad Gumi explicitly mentions the damage caused by an eruption of Mount Agung. Especially destructive were the pyroclastic flows that surged down the mountain, following the course of rivers.

Many villages were destroyed, as well as the dry rice and the paddy fields. Ravines became hills and hills became ravines. The wellsprings were destroyed, engulfed by fire. [...] The destruction went as far as the betel plants, the fruit trees and the coconut trees, as far as the dry rice fields. The aqueducts were destroyed and could not be quickly rebuilt. Everything was damaged. The rivers Bungbung and Yeh Lajang both destroyed paddy fields, and the bathing place at Babi was all filled up. The river Bangkak destroyed the dry rice fields at Susut. The rivers Selat and Barak both destroyed paddy fields.

The destruction caused by natural disaster is not merely physical. The Babad Gumi invokes the Hindu figure of Kala Agni Rudra, who is a manifestation of Shiva in his role as universe destroyer. ‘When the earth's lifespan had come to an end,’ it reads, ‘Kala Agni Rudra devoured Mount Agung.’ In certain strands of Hindu thought, such destruction occurs at the end of a cosmological cycle. After that, the universe is created anew. This choice of imagery suggests that the historian who recorded this eruption wanted to convey its apocalyptic character, while alluding to the renewal that always follows destruction.

Political renewal

The imagery of Kala Agni Rudra suggests that natural disasters were not seen as merely destructive. Volcanic eruptions, in particular, have a complex effect on human welfare. In the short term, eruptions displace populations, destroy food sources and poison water supplies. But in the long term, ash deposited by eruptions produces fertile soils that can sustain intensive agriculture. This double-edged impact may explain why local literature depicted volcanoes as both sources of destruction and of renewal.

In Java, the idea of natural disaster was closely linked to that of political change and renewal. When the Javanese king Hayam Wuruk was born in 1334, there was an eruption of Mount Kampud (present-day Kelud) in East Java. The Deśavarṇana is a poem written to celebrate this king. It describes the eruption as a portent of his greatness.

The omens that he would become an extraordinary person were

Rumbling earthquakes, ash rain, thunder and lightning twisting in the sky.

Mount Kampud erupted. The criminals and traitors wailed, choking to death.

Here the positive effects of natural disaster are emphasised. It presages the birth of an excellent king. Its victims are not innocent bystanders but enemies of the state who are justly punished. This passage implies that the destruction caused by the eruption allows for the renewal embodied in the new king's reign.

Similar ideas prevailed after Islamic kingdoms became established in Java. The Babad Tanah Jawi describes an eruption of Mount Merapi that set the scene for the emergence of Senapati as the new ruler of Java in the late sixteenth century. The gods of Mount Merapi had previously made a promise to Senapati's allies that they would appear when it was time for a new king.

In the sky there was a thundering sound; that was a sign that the demons, fairies and spirits of the mountain had come to help fight the battle.

This passage illustrates a very old feature of Javanese spirituality: the association of mountain deities with royal power. This tradition was maintained in recent years by Mbah Maridjan, a Yogyakarta court servant who acted as the guardian of Mount Merapi, until his death during the eruption of 2010.

Fortune-telling

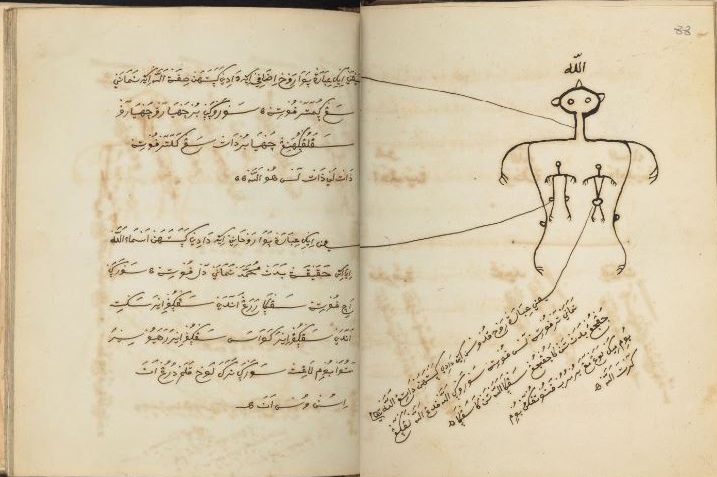

The intimate connection between the natural and human realms is often expressed in terms of disasters being ‘signs’ of other events that will happen to people. The Malay text Kitab Ta'bir, written in the 1820s, explains the correlation between earthquakes and the welfare of society. The connection is structured according to the Islamic calendar.

And if an earthquake occurs in the month of Muharram of an Alif year, then it is a sign that there will be much strife and disease will be severe in that year [...] And if an earthquake occurs in the month of Syawal of a Jim year, then it is a sign that goods will be cheap and society will be healthy and safe in that year.

The predicted events are not caused by the earthquakes themselves, but are foretold by the timing of the earthquakes. The formulaic layout of this text indicates that it is a divination manual for readers to predict the future. Divination has an ambiguous place in Islam. While the practice is found in many Muslim societies, some scholars are uncomfortable with its resemblance to prohibited forms of magic. It is notable, therefore, that the author of the Malay Kitab Ta'bir quotes a phrase from Al-Ghazali, a central figure in orthodox Sufism, apparently in defence of the text's divinatory content.

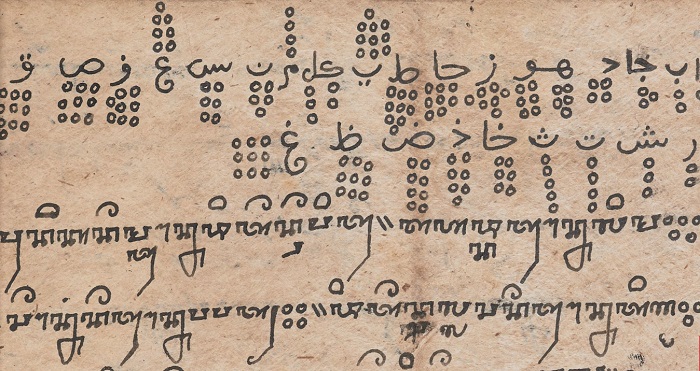

Similar practices are found in Bali. There, divination is often performed using painted diagrams called palelintangan (star calendars) and palindon (earthquake calendars). In this Hindu context, the correlation between earthquakes and events in the human realm are understood as effects of the meditation of particular deities. Adrian Vickers, in his 2012 book on Balinese art, explained how a particular theory of causality is embodied in palindon paintings:

Deities do not directly cause the events predicted by each month's earthquakes. Rather, the divine power or sakti of each deity's meditation has sets of indirect consequences, including the earthquakes caused by the act of meditation. Events, good and bad, are indirect manifestations of divine power working in the world, and are not related to intentions.

By examining how disasters are talked about in these texts, we gain broader insights into Indonesian ideas about causality and the action of deities in the natural and human worlds.

Traditional views

Natural disasters have always played a major role in the lives of Indonesians. This is reflected in the inscriptions, manuscripts and paintings they created over hundreds of years. The view that emerges from these traditions is of disasters as ambivalent events. They are certainly destructive, but they sometimes foretell good things to come. Natural disasters do not happen randomly, and their significance is not merely physical. Rather, they are linked to the political and social worlds in complicated ways. Somewhere behind them, divine agency is always at play.

Wayan Jarrah Sastrawan (jarrah.sastrawan@sydney.edu.au) is a PhD student of Asian History at the University of Sydney.