Laurie Margot Ross

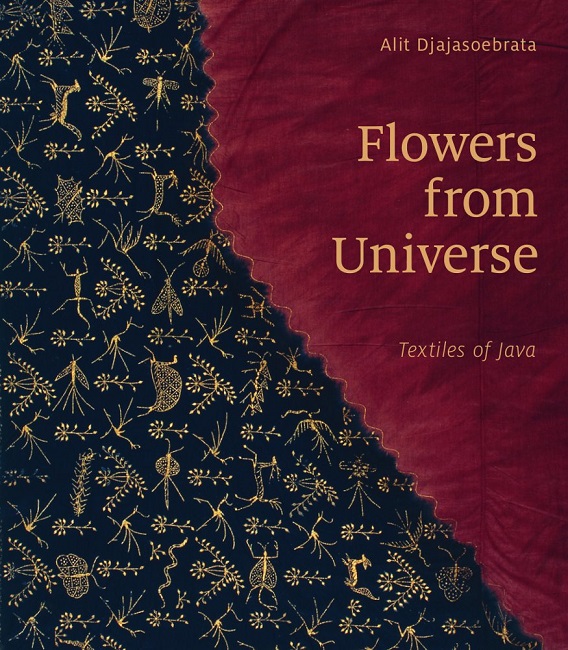

The title of this long-awaited English translation of Alit Djajasoebrata’s original Dutch text is neither typo, nor haiku. Rather, Flowers from Universe, like the original Dutch title, Bloemen van het Heelal, is the literal translation of the Javanese term ‘sekar jagat’ – the name of a batik design. And the book, rather than unfolding in linear, chronological fashion, may instead be likened to the Javanese puppet theatre, whose vignettes are woven together by diverse strands. The word ‘flower’ itself (kembang) has multiple meanings that pertain to nature’s role in Javanese textiles. For example, it may signify a specific flower that is used as a motif, or one whose colour is used as a natural dye.

Flowers is packed with illustrations, spanning colonial era maps, prints, drawings, textiles and photographs. The 18 succinct chapters discuss such diverse topics as mountains, cosmic trees, pigment and synthetic dyes, Java in the sixteenth century, ritual milestones, Dutch women in Java, food offerings, Chinese traders and local legends.

It is not usually integral for a book review to discuss the biography of the book’s author. Flowers is an exception. Alit Djajsoebrata’s background informs this book, which draws equally from her memories, history, and keen aesthetic.

Alit was raised in the multicultural home of her Sundanese mother (discussed in the book) and Dutch administrator father. Her father, Bientje Roep, was an early supporter of Indonesian independence and an architect of the young republic’s short-lived Dutch-shaped Constitution. With Indonesia’s sovereignty, the family moved to the Netherlands, where Alit became the curator of Indonesian and Malay Civilisations at the Rotterdam Museum of Ethnology. Her Dutch lineage in Indonesia and Indonesian lineage in the Netherlands informs her sensitivity to the Other. This includes articulations of Chinese and Indian culture.

After the 1984 publication of the original edition, additional research was conducted, some of which is included in the English translation. Also included in several chapters are her personal reflections on textiles and contemporary culture in Indonesia. These updates are not revisions per se. Rather, they supplement some of the ideas introduced in the original edition. As such, the book is best understood as reflecting the zeitgeist in which it was written: the mid to late twentieth century, during former president Suharto’s New Order regime.

During the New Order, some local ‘traditions’ discussed in the book were discontinued or banned and new ones invented. Stark as such changes were, they were also continuous with earlier Dutch practices in colonial Java, which were maintained during the tenure of Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno. Beyond bridging Indonesia’s oft-romanticised Hindu-Buddhist past with its Dutch and independence eras’ autocratic inflections, Djajasoebrata invites the reader to consider Indonesia’s fledgling democracy under reformasi. This includes more conservative Islamic interpretations of gender and the arts. These combined factors are the prism through which textile development in Java is examined here.

Most European and American books devoted to Javanese textiles stress the aesthetics of elite society. Flowers, far from excluding or lingering on elite art as a special category, engages with how ‘low’ (popular) and ‘high’ (elite) art inform each other, looking at legends, colour, symbolism, textile-making processes and political interventions, and their hidden and overt and concealed and revealed meanings. At its core, it is an exploration of the power of opposites. Inherent in such comparisons is how different rural West Javanese (Sundanese) people and textiles are from their better-known and privileged Central Javanese neighbours.

Sunda has long been marginalised in both Indigenous and Dutch scholarship, while Central Java – with its palace intrigues, literary court marvels and Hindu-Buddhist shrines – was elevated. Flowers asks the reader to think outside the box about these two centres of Indonesian textile production as well as the foreign sources that influenced them.

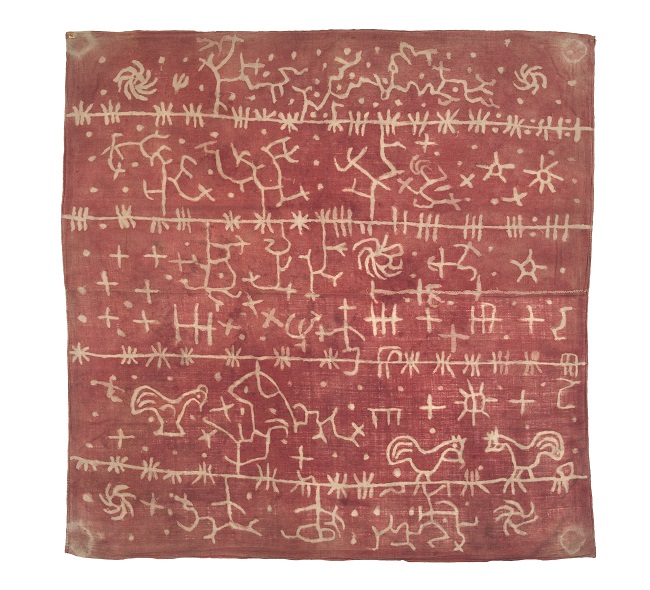

The examination of motifs in Flowers is particularly valuable. The author provides rich examples of the less-refined, more expressionistic Sundanese textiles, speaking to the distinctive geopolitical influences and struggles of the two cultures.

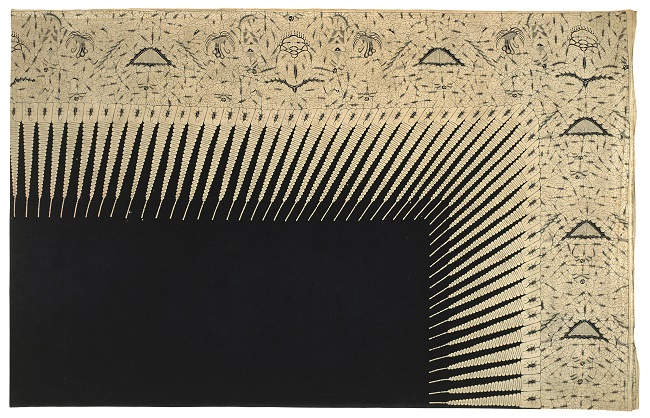

The kain simbut (cotton blanket) discussed in Chapter 3, for example, is revelatory in depicting the visual power of secrets in Sunda. This is different from the refined aesthetics of nature that usually dominate discussions about textiles from the Surakarta and Yogyakarta courts. The colour of the kain simbut is created by smearing dye with the brush of a coconut husk. The cloth itself is typically monochromatic and with a coarser weave, whose iconography emphasises talismanic protective forms. This process stands in sharp contrast to the delicately drawn klacap kumitir (shivering flashes) motif worn by a ceremonial guard at the Yogyakarta palace, which is made from the finest cloth and hand drawn with utmost attention to detail.

Just when the reader thinks the meaning of a given pattern is understood, a different interpretation is offered. For example, the widely discussed motif, parang rusak (broken cleaver) which consists of an ‘exalted pattern organised in diagonal rows.’ This pattern is often worn by men and women at weddings and other rites of passage. ‘Broken cleaver’ refers to the elongated knife carried by peasants that are used for a variety of purposes, including cutting down forest brush, cracking open a coconut, or carving a puppet from cowhide. However, parang may also refer to the Javanese term for rock, karang. This suggests a stone that has withered away from being repeatedly pounded by ocean waves. In another example, this pattern is compared to rays of sunlight that allow foliage to continually sprout. Embedded in this pattern, then, are the polarities of fertility and destruction.

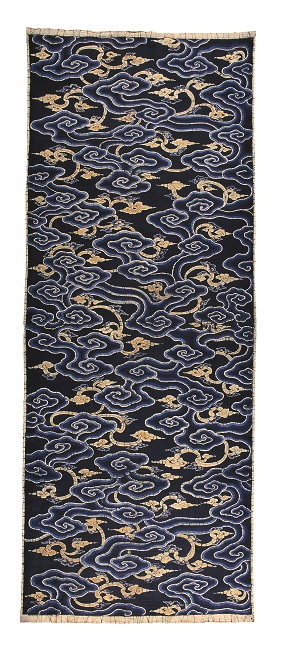

One chapter is dedicated to Java’s north coast trade portal, Cirebon, with its striking Chinese influences. Perhaps the most emblematic motif associated with the region is the mega mendung (low-lying clouds). Like the parang rusak motif, it represents fecundity. It is most commonly seen on batik from the area; however, variations are depicted in household objects such as wood-carved plates and bowls from Cirebon’s royal courts.

Dutch inspiration of objects associated with textile production is also considered. In the chapter ‘Weaving Myths of Sunda,’ for example, the relationship between the animal world and textiles is examined through a legend first discussed in an early twentieth-century essay by the Dutch curator, CM Pleyte.

The legend is accompanied by a photograph of the consort of a Sundanese district head seated at her spinning wheel (circa 1910). Djajasoebrata introduces a late nineteenth-century sewing box belonging to this consort now held in the Dutch collection at the Stichting National Museum of World Cultures. Its base is made from the hoof of a rhinoceros – an animal that, according to the legend, is said to test the will of the prince. In addition to its symbolic meaning, rhinoceros skin is a particular aesthetic depicted in the jamblang (checkered) pattern popular in the woven cloths worn by Sundanese men. The metal lid of the box is secured with a clasp with a hand-tinted photograph of the Javanese woman who gifted the sewing box, signaling the sentimentality of women’s work in colonial Java. The combination of nature and modern technologies brings domestic and foreign aesthetics into one orbit. The same is true of the commerce side of Dutch-Indonesian relationships.

The tradition in which a Muslim bride gifts her groom a special textile to protect his Qur’an may continue, however, this gesture is not merely sentimental today. The growing expectation that Javanese men will pray at the mosque five times a day makes the wrapper increasingly functional. This bridal cloth was long produced on Java’s northwest coast. By the early twentieth century, it was manufactured and exported from Leiden, demonstrating Holland’s participation in and profiting from a local Muslim tradition.

New shoots

The title of the closing chapter, ‘Tunggak semi: New Shoots from an Old Trunk,’ confers that the new must build upon the old. The chapter focuses on the contributions of several twentieth-century modernist batikkers who achieved this, most notably the contemporaries Go Tik Swan, or Go (aka Hardjonagoro, 1931-2008) and Iwan Tirta (aka Nursjiwan Tirtaamidjaja, 1935-2010).

Go, an Indo-Chinese intellectual, pioneered combining classical Central Javanese motifs with the bright colours associated with Chinese traders and settlers along the north coast. His innovations were so enjoyed by the Surakarta court that they appointed him a bupati sepuh (elder regent). Like Go, Tirta fused domestic and global concerns. However, Tirta’s influence was most deeply felt in the fashion world. He was the go-to designer for the Suharto government, which commissioned him to design batik shirts specific to each foreign dignitary that visited Indonesia. Nelson Mandela was so pleased with his batik shirt designed for the 1990s APEC summit in Jakarta that, from that point on, he wore batik exclusively on international official occasions.

The reader might conclude that the target audience for this book would be hobbyists and undergraduate students, rather than scholars and specialists. Certainly, Flowers is an excellent primer on textiles in Java. It is also true that specialists will be familiar already with the history of Java. However, the way it is explored here – through the prism of textiles – makes this book unique. So, too, are the interconnected chapters dependent upon Djajasoebrata’s multi-linguistic capabilities that incorporate Sundanese, Javanese, Indonesian, Dutch and English.

As with any innovative book that breaks new ground, there is much to praise as well as room for improvement. The accessibility of Flowers to non-readers of Dutch and Indonesian is especially important in the glossary and (though dated) bibliography. The many foreign terms translated in the glossary are conveniently subdivided by the following categories: techniques, materials, dyes, textile types, garments, motifs and implements.

My criticism of the book, though minor, pertains to mostly technical misses. Some illustrations are explored in greater detail than others, whetting the appetite for deeper contextualisation. Moreover, several citations found in the text and footnotes are either misalphabetised or omitted in the bibliography. Where citations are lacking, it is difficult to determine whether the ideas expressed are fact or the author’s opinion. These little quibbles aside, Flowers from Universe is a must-have reference that allows the reader to understand the textiles of Java from the inside out and the outside in as well.

Djajasoebrata, Alit, Flowers from Universe: Textiles of Java, Volendam, The Netherlands, LM Publishers, 2018. Introduction by Toeti Heraty N Roosseno. Translation of the original Dutch-language version: Bloemen van het Heelal: De kleurrijke wereld vande textile op Java , Amsterdam, Luitingh-Sijtoff BV, 1984

Laurie Margot Ross (lauriemargotross@gmail.com) is the director of the Glocal Matters in upstate New York, a research center that focuses on religion, visual culture and performance in the Global South. She is the author of The Encoded Cirebon Mask: Materiality, Flow, and Meaning in Java’s Islamic Northwest Coast (Brill, 2016).