Ron Witton

In the 1960s I completed two honours degrees in Indonesian and Malayan Studies at the University of Sydney and gained a doctoral degree from Cornell University focusing on Indonesia. Since then I have taught Indonesian social sciences, worked as an Indonesian interpreter and translator, and visited Indonesia many times, teaching for a while at Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta. With that background, I thought I had fairly good grounding in Indonesian history and society.

This confidence was profoundly shaken when, by chance, I was in the New South Wales country town of Coffs Harbour and happened to visit the town’s art gallery. I was confronted by an exhibition titled ‘Landscape of the Soul: A Mixed Media Exhibition Illustrating the Experience of European Dutch and Eurasian People in Indonesia During the Japanese Occupation, the Revolution and After’.

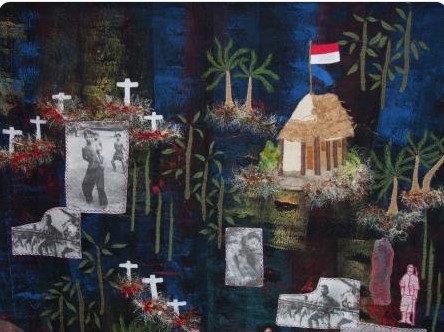

What I learnt from this striking exhibition was that soon after Indonesian independence was declared on 17 August 1945, the most horrific massacres of men, women and children who were of mixed Dutch and Indonesian descent took place. A profoundly important historical event, but one that outside of The Netherlands and to a small extent Indonesia, with few exceptions, has hardly entered academic, let alone broader historical consciousness.

I left the exhibition and began my own research about what happened in that period. I have come to realise that the main reason I was unaware of those events is that it is only fairly recently, in the last 10 years, that academic scholarship has begun to examine those events and their significance. Moreover, seen from the Dutch and Indonesian perspectives, they remain highly contested historical events.

In my readings I was quickly introduced to two terms: binnenkampers and buitenkampers. Binnenkampers (meaning ‘in-campers’) refers to the over 100,000 Dutch nationals who were held from 1942 to 1945 in Japanese internment camps while buitenkampers (‘out of-campers’) refers to the over 250,000 Dutch nationals who remained outside the camps for the duration of the war. The majority of this second group were of mixed Indonesian and European descent (Eurasians). It should also be remembered that among the Eurasians there was a comparatively small number who were of mixed Chinese-European descent.

Dutch colonial law provided for the Dutch citizenship of the father to be passed on to children of mixed parenthood, and so the majority of Eurasians were considered to be Dutch nationals. Before the war, while there was very little racial strife, the ‘Indos’, the somewhat derogatory term used to refer to Eurasians, had a sharply demarcated social position within the colonial society of the Dutch East Indies. Having often had more schooling than native Indonesians and being fluent in Dutch, they generally had relatively good employment prospects compared to most Indonesians. However, they were generally restricted to inferior or limited positions such as clerks, petty officials and non-commissioned officers. Nevertheless, they generally felt themselves to be part of Dutch society, albeit colonial society, and had a high level of loyalty to the Netherlands.

Ironically, some Eurasians had been party to a very early nationalist attempt in 1911 to form a political party to promote an independent country free from The Netherlands. However, the Dutch government refused to recognise the party and exiled its leaders. As Indonesian nationalism grew in the 1920s and 1930s, Eurasians increasingly saw their fortunes linked to the colonial order.

This is the background to the events immediately following the declaration of Indonesian independence when there occurred what has been described as a ‘brief genocide’. The Japanese had trained many young Indonesians in martial arts and had instilled in them the idea that the ‘enemy’ were the Americans, the English and the Dutch. With the surrender of the Japanese and the immediate declaration of Indonesia’s independence by Sukarno and Hatta, the prospect of the re-establishment of Dutch rule resulted in an intense level of paranoia about the Dutch and anyone who supported the Dutch. Suspicion extended to the British troops who landed and were ordered to restore Dutch rule, and to local Dutch nationals who were often characterised as spies and supporters of NICA, the Netherlands Indies Civil Administration.

Again, ironically, the Dutch who were in internment camps were to a certain extent protected from such attacks. However, it is estimated that many thousands of Eurasians had no protection at all and were brutally massacred by Indonesians who saw this as a way of expressing their support for independence. It is significant that as a student of Indonesian history I was taught about Dutch soldiers such as Raymond ‘Turk’ Westerling who massacred many thousands of Indonesian civilians in support of Dutch counter-insurgency efforts against the Indonesian nationalist movement. However, we were never taught the names of Indonesians, such as Sabarudin, who helped coordinate and carry out the massacre of Eurasian men, women and children.

While there has been some attention paid to the atrocities carried out in such locations as the Simpang Club in Surabaya, there are many sites of massacres that have been lost to the historical record. The parallel with the little known locations of many of the 1965 massacres that occurred throughout Indonesia need hardly be stressed.

In the last 10 years a body of scholarship examining this period of Indonesian history has emerged. Frances Larder’s exhibition makes a contribution to this end, to comprehend the historical trajectory of events before, during and after the Japanese occupation. Of particular concern has been the effect of those horrific events on the children of Eurasians in that period, and indeed Frances Larder was a child during that period. Now quite elderly they remain the only eyewitnesses. Their vivid recollections of that terrifying period and the effect it had on their lives is what makes the 2014 Dutch documentary (with English subtitles) Buitenkampers, so heartbreakingly moving.

An exhibition

Frances Larder’s exhibition, through her wonderful wall hangings, supplemented by historical mixed media materials, records Eurasian colonial life, the privations of the Japanese occupation, the killings following the Japanese surrender, the exodus of some 100,000 Eurasians to Indonesia after independence, their alienation and isolation in Holland, and the subsequent migration of some of them to Australia.

Sydney’s Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre is the second gallery to host her exhibition. This is an exhibition that deserves to travel from gallery to gallery across Australia to help further Australia’s understanding of both the diverse heritages that migrants have brought here and the particular experience of Australia’s Indo-Eurasian citizens.

Frances Larder, ‘Landscape of the Soul: A Mixed Media Exhibition Illustrating the Experience of European Dutch and Eurasian People in Indonesia During the Japanese Occupation, the Revolution and After’. Frances can be contacted on franceslarder@gmail.com.

Ron Witton (rwitton44@gmail.com) gained his BA and MA in Indonesian and Malayan Studies from Sydney University, and then his PhD from Cornell. He has lectured in Sociology and Asian Studies in universities in Australia and Indonesia. He still works as an Indonesian interpreter and an Indonesian and Malaysian translator.