This is the third in a series of reviews by Joost Coté of recent Dutch publications re-examining their colonial history.

Piet Hagen’s overview of the colonial wars that have taken place in Indonesia over the last five centuries is the most recent example of a growing flow of publications challenging the existing standard Dutch account of its colonial history.

On the face of it, Hagen, an experienced journalist, has a quite straight forward objective in Colonial wars in Indonesia: to list all the wars, revolts and skirmishes involving Europeans that have taken place within the Indonesian archipelago between 1509 and 2002 (East Timor being the last mentioned). How many such military actions were there in that period? Possibly 500 he suggests in a recent interview; his book refers to around 300 separately identifiable and historically referenced events involving the Netherlands, roughly divided between the VOC era (1600 to 1796), and the colonial era (1816 to 1961).

For those interested in Indonesian history this tally shouldn’t come as much of a surprise but what should be of interest to readers of Inside Indonesia is the fact that this and other books on the topic (see links to previous reviews at top of article) have recently begun to appear in the Netherlands.

History re-examined

Hagen’s book can be seen in the context of (although not part of) a current four-year (2017 to 2020) Dutch government-funded research project into one of these ‘events’ – the Indonesian War of Independence, fought from 1945 to 1949. This research project, details of which are available for public scrutiny by emailing info@ind45-50.nl and by subscription newsletter, has created a significant debate in the Netherlands – and in Indonesia. Originally titled Decolonization, Violence and War in Indonesia, 1945-1950, the research is being conducted across three Dutch research institutes and has a cooperating counterpart in Indonesia where researchers insisted on adding the word ‘Independence’ to the project’s original title. This change gained official Dutch government approval in 2016.

Perhaps predictably on internet sites linked to veterans and other groups with close links to a colonial past, there have been strong negative responses to this unravelling of what had been a firmly packaged and largely positive national narrative. But there is also a growing scepticism, particularly in Indonesia (see for instance Yayasan Komite Urang Kehormatan Belanda), as to whether this project will arrive at ‘the truth’. It is anticipated Hagen’s book will experience similar criticisms.

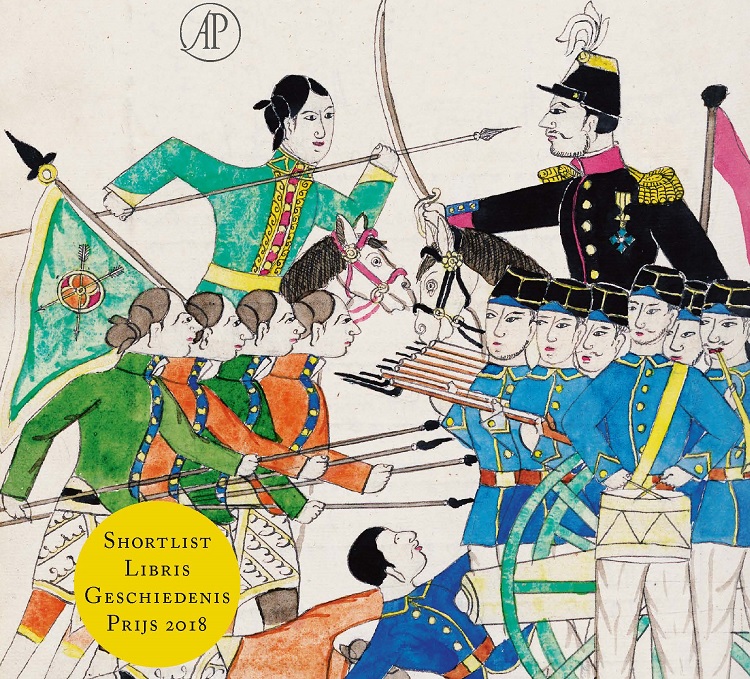

The specific objective of Colonial wars in Indonesia is encapsulated in its last chapter which lists and briefly summarises the majority of these colonial ‘events’ . If this were all, the publication would amount to little more than an extended Wikipedia entry and indeed a dedicated search on Wikipedia, or consultation of the Encyclopaedia of Wars can deliver a similar result. But what is interesting is the author’s motivation for writing the book. Hagen has explained that the book is the outcome of a personal journey after he read Peter Carey’s account of the 1825 to 1830 Java war ( The Power of prophecy: Prince Diponegoro and the end of the Old Order in Java , 2014). Impressed by the scale of this battle and Carey’s portrayal of Diponegoro’s motivation in resisting the Dutch, he was equally struck by the fact that it ‘was completely absent in the Dutch collective memory’.

Hagen’s reflection is reminiscent of Australian historian Henry Reynolds’ questioning in his seminal book, Why weren’t we told? (1999) in relation to Australian colonial history. About the Dutch case Hagen gives a similar answer: ‘It is a result of colonial thinking.’

This, then, is the motivation for the book. He seeks to provide the contemporary Dutch generation with information about the history of the country’s colonising practice and to provide some insight into what motivated Indonesian resistance to this intervention. Hagen dedicates it to ‘the memory of the millions of victims that accompanied the colonial wars’.

In 2007, Stef Scagliola was perhaps the first to clearly set out the existential problem for the Dutch nation when the first stirrings of this ‘national conscience’ began to surface. She advocated a ‘democratisation of history’ but was forced to concede then that ‘there is no interest group sufficiently motivated to tackle the subject of Dutch war crimes’. Ten years later Leiden academic Ethan Mark felt it necessary to remark about Dutch academia: ‘It is remarkable to me how much resistance … still remains [to] addressing this problem of the over-representation of the coloniser and his standpoints’.

An official response to this emerging revisionary perspective on the colonial past can perhaps be dated from a successful 2011 Indonesian-initiated compensation case in relation to the massacre perpetrated during the 1945 to 1949 war at Rawagede. This ultimately resulted in an official Dutch apology in 2013. Subsequently there have been a further five compensation cases related to Dutch war crimes committed in Java in 1946 and 1947, brought by the families of victims, including those related to the South Sulawesi massacre perpetrated by the infamous Captain Westerling. These cases have taken history out of the archives and into the public consciousness.

Other signs that history is coming ‘unstuck’ is evidenced by a photographic exhibition at the Amsterdam Resistance Museum where visitors can compare photographs of Indonesia’s War of Independence that were made available to the Dutch public at the time, and those which were censored.

So what does Hagen’s book contribute to this relatively recent Dutch public conversation?

In 25 briskly written and sparsely referenced chapters Hagen sets out to enlighten Dutch readers about the military campaigns that their ancestors (and others) perpetrated against Indonesians. The chapters provide a chronology of selected regional campaigns or the violent consequences of particular colonial policies. Despite its overall length, it is an easy read; Hagen employs his journalistic experience to provide clear, concisely detailed accounts in straightforward, everyday language, though he provides little stimulus for re-evaluation.

Commentary and analysis is saved up for two penultimate chapters, ‘The colonial system: Exploitation, repression and violence’, and ‘Who gave you the right? Contemporary criticisms’. The first does little to question ‘colonial thinking’, and its failure to do so is further compounded by Hagen’s somewhat lame conclusion that questioning ‘history’ would merely land one in unproductive ‘what/if’ speculation. The latter chapter repeats the well-known criticisms of colonial practice made by early twentieth century advocates of the so-called ethical policy, which, as Bijl (2015) has shown, has provided the major defence of colonial practice ever since.

There is no reference to contemporary criticism of the ‘politionele acties’ (police actions) undertaken during the 1945 to 1949 campaigns, other than the long recognised Westerling atrocities in South Sulawesi – Rawagede is not mentioned. Ultimately, Hagen’s seems to conclude with a justification of the past:

‘Without the pacification and centralisation under Netherlands rule the nationalist movement would have found it much more difficult to realise a unitary state.’

Limited in its aims, Piet Hagen’s book may well succeed in reminding his Dutch readers of the Netherlands’ colonial past. This contribution could be extended if this and similar publications reporting on revisions of the historical record were made available in Indonesian and English translation.

Piet Hagen, Koloniale oorlogen in Indonesië :Vijf eeuwen verzet tegen vreemde overheersing, [Colonial wars in Indonesia: Five centuries of resistance against foreign domination] De Arbeiderspers, 2018.

Joost Coté is a senior research fellow at Monash University.