Both sides are playing the God card in their own ways

Nadirsyah Hosen

At the gates of hell, an Indonesian guy, let’s say Budi, meets Hitler who killed six million Jews, and Pol Pot who committed genocide against nearly two million Cambodians. They ask Budi, ‘How many people did you kill?’ Budi replies, ‘None. Actually, I was a good Muslim who prayed five times a day, fulfilled my obligations of fasting at Ramadan, paying charity and even visiting Mecca for the pilgrimage.’

Both Hitler and Pol Pot are shocked to hear this. ‘So what exactly did you do, that you ended up here in the hell?’

‘I am not sure; perhaps it was because I did not follow what the preachers said during Friday sermon, not to vote for Jokowi [President Joko Widodo] in the elections.’

This fable illustrates the return of political and religious identity in the lead up to the Indonesian parliamentary and presidential elections of April 2019. This started in the 2014 presidential elections when Jokowi was nominated for the first time. Although he won the election, he suffered from a smear campaign that questioned, among other things, whether he was a genuine Muslim.

When Jokowi left his post as Governor of Jakarta to take up the presidency, it opened the door for his deputy, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok), to assume the governorship. Ahok fell from his position in the Jakarta gubernatorial election in 2017 after his political opponents successfully weaponised Islamic sentiment against him. Friday sermons were full of hate speech, and preachers even warned people that they would burn in hell if they voted for Ahok, an ethnic Chinese-Christian.

Ahok’s efforts to remedy Jakarta’s administrative and social problems were almost entirely overshadowed by the claim that he had mocked a Qur’anic verse (al-Maidah: 51). Mass demonstrations were held in the city. The court sentenced Ahok to two years’ jail, based on the blasphemy provisions of Indonesia’s Criminal Code.

Jokowi seems to realise that the same ‘Islamic sentiment’ card could be used against him in the 2019 elections. In a surprise move, under pressure from his coalition parties, he selected Ma’ruf Amin as his running mate. Among other reasons, Ma’ruf was seen as a safe candidate who could prevent the ‘Islamic’ card being played against Jokowi. As a senior leader of the mass Islamic organisation Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and MUI (Indonesian Ulema Council), Ma’ruf provides Jokowi with a trump card of his own.

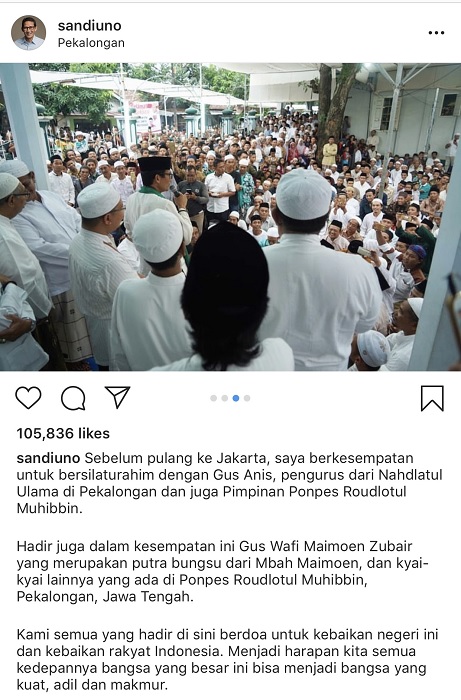

It would appear that Jokowi is also playing the God card, not only to save his position as president, but perhaps also to save people like Budi from going to hell. Since his nomination, Ma’ruf has paid visits to pesantren (Islamic boarding schools) belonging to NU. He has met Islamic leaders, particularly from his own area of West Java, where Jokowi lost badly in 2014. Ma’ruf has used Islamic terms to criticise Jokowi’s opponents, and even to claim that Jokowi is also a santri (a student of a pesantren) – a claim that can easily be refuted. Even then, Ma’ruf may not have done enough to upgrade Jokowi’s credentials in the eyes of Muslim voters.

To Jokowi’s surprise, his opponent Prabowo Subianto ignored the vice-presidential recommendations made by Habib Rizieq Shihab from the FPI (Islamic Defenders Front) and other conservative groups. Prabowo picked as his running mate Sandiaga Uno, who has no background as a Muslim activist, instead of choosing one of the two alternative candidates with strong Islamic backgrounds: Salim Segaf and Abdul Somad, suggested by Rizieq’s groups.

Rumours about how and why Prabowo picked Sandiaga Uno, one of Indonesia’s wealthiest Indigenous businesspeople, have circulated on social media. PKS (Justice and Welfare Party), an Islamist party that has supported Prabowo since 2014, quickly responded by labelling Sandiaga as a ‘post-Islamism’ santri, meaning he is devout despite not showing outward signs of piety – this is despite the fact that Sandiaga studied at a Catholic school rather than a pesantren. Rizieq and his groups ultimately approved of Sandiaga as Prabowo’s running mate, but this does not mean Prabowo’s camp will stop using the ‘Islamic sentiment’ card against Jokowi.

While carefully urging their supporters not to attack Ma’ruf, a respected Islamic figure, the Prabowo-Sandiaga team continues to attack Jokowi’s Islamic credentials, particularly in social media and at Friday sermons. They sent this issue viral when Jokowi, in his Javanese accent, asked people to recite the ‘al-Fatekah’ chapter in the Qur’an. The correct pronunciation is ‘al-Fatihah’. They attacked Jokowi for not knowing how to pronounce the name of this chapter properly.

Ma’ruf was criticised when he addressed Christian leaders using the Islamic greeting: Assalamu ‘Alaikum wa rahmatullahi wa Barakatuh. A general understanding is that this greeting can be used only between Muslims. According to Prabowo’s supporters, this indicated that Ma’ruf had sold out his Islamic beliefs just to get votes from Christian leaders. They ignored the fact that there are many different opinions in Islamic literature about the greeting. Ma’ruf could argue, with his extensive Islamic knowledge, that he selected an opinion that allowed him to greet Christians in that manner.

Both candidates are thus using the ‘Islamic’ card. The only difference is that Jokowi’s camp is using it to promote his credentials as a good Muslim, whereas Prabowo’s camp is using it to continue attacking Jokowi. The question is why are they not also using it to promote Prabowo’s own claimed Islamic credentials. That might be too risky.

Admittedly during his military career, Prabowo was known to be a member of the ‘green’ military faction, comprising generals who were close to, and supported, Islamic groups. The opposing ‘red-white’ faction of the military comprised generals who took a neutral position, not siding with either Islam or the State.

Prabowo’s membership of the green faction provides him a long-standing relationship with Islamists dating to the Suharto era. Even so, many people – including Prabowo’s own supporters – question whether Prabowo is a practising Muslim. Moreover, many of Prabowo’s family are not Muslims, for instance his brother Hashim. This explains why his supporters have chosen to attack Jokowi’s Islamic credentials, rather than building a more positive image of Prabowo as a good Muslim.

The dilemma for Jokowi’s camp is whether they want to use the ‘Islamic sentiment’ card to attack Prabowo. When there was a suggestion from Prabowo’s camp that the presidential debate should be conducted in English (to mock Jokowi’s Javanese accent), Jokowi’s camp quickly responded by suggesting that the debate should be in Arabic (to mock Sandiaga’s new label as a santri though he can’t speak Arabic). Jokowi’s camp even repeated Vice-President Jusuf Kalla’s statement from the 2014 campaign calling for a Qur’an recital test between Jokowi and Prabowo. Jokowi may have a Javanese accent, but at least he is known to be able to read the Qur’an, while the public has never heard Prabowo reciting the Qur’an.

Although both candidates have used the 'Islamic' card, albeit in different ways, neither side has yet backed it with substantive programs. Jokowi, with an infrastructure focus in his development program, has not provided us with a clear idea of what he is going to do regarding pesantren, Islamic banks, Islamic universities and Islamic organisations. How can he counter radicalisation in schools and mosques? Even with Ma’ruf at his side, he hasn’t presented a clear deradicalisation program as yet.

Prabowo’s camp, whose campaign focuses on economic issues, has similarly been busy criticising Jokowi’s performance and Islamic credentials, but what specific programs can they offer that help Muslims, particularly in rural areas, who suffer financial hardships? This remains a missing element from the current debate. The Grameen Bank in Bangladesh is one model Prabowo could adopt, but so far we have not seen any real programs for Muslims at the grassroots level.

Of course the campaign still has over a month to run and these dynamics could shift again as election day draws nearer and the stakes heighten for the two camps. To date, Jokowi maintains a comfortable lead in the polls, despite attacks on his devotion as a Muslim. What is clear is that both sides are playing the God card in their own ways in pursuit of an edge in the election.

And so, back to Budi in hell. Budi might well protest to God, ‘Why did you put me here in hell with Hitler and Pol Pot? Can’t you see that what I did is nothing compared with them? Whom did you choose in the Indonesian presidential election?’

God smiles. ‘Sorry, I chose golput (abstained from voting)!’

Nadirsyah Hosen (Nadirsyah.Hosen@monash.edu) is a senior lecturer at the Faculty of Law at Monash University and the chair of the advisory board for the Australia-New Zealand branch of Nahdlatul Ulama. He is an associate of the Centre for Indonesian Law, Islam and Society at the Melbourne Law School.