Jorgen Doyle and Hannah Ekin

There are many wish-images waiting to be represented that have given Jakarta a life based on wishing. / Abidin Kusno

Over 11 days and nights in February of this year, we walked across the 42 kilometres of Jakarta’s historically neglected and currently much contested northern coastline. During our journey, our hosts included a fishing community currently facing eviction and that is subject to flooding from the airport dam just upstream, and from rising sea-levels. We also stayed in a ruko (a four-storey integrated shophouse); a kampung (urban village) controversially evicted two years ago; an airbnb on the thirtieth floor of a luxury housing block above a mall (the sort of development responsible for the flooding); an artificial beach in the faded Suharto-era theme park of Ancol; a passenger ferry terminal; and a vast housing block outside of Jakarta where waterside communities have recently been evicted to. The housing block is intended to become the largest in Southeast Asia.

Walking trail near Soekarno Hatta / Doyle & Ekin

Our walk stretched from kampung Dadap, a small fishing community just outside the west boundary of Jakarta, to the housing estates of Marunda, on the easternmost border of the city. We crossed areas and neighbourhoods of prolonged urban disinvestment and, conversely, new areas of speculative hyper-investment. The walk was the first step in our ongoing endeavour to come to terms with and intervene in the huge spatial, social and ecological changes currently taking place in North Jakarta.

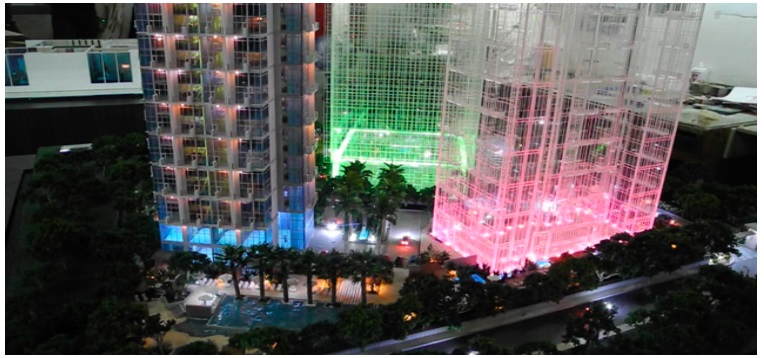

Hongky's Model / Doyle & Ekin

These changes are notably occurring through the Jakarta administration’s proposed Great Garuda Sea Wall project (GGSW) – a 32-kilometre seawall designed to enclose Jakarta Bay and solve the city’s flooding problems. The plan will ‘Dubai-ify’ Jakarta’s coastline, adding, among other things, a huge waterfront city built on a series of artificial islands in the shape of the Garuda – an eagle, and Indonesia’s national symbol. This megaproject is laden with symbols, drawn from both the nation’s past, and from circulating images of ‘global cities’ such as Singapore, New York City and Hong Kong. It embraces an imagined prosperous future in a globalised world and is promoted conspicuously as a compelling vision of the future.

Our ongoing research in Jakarta looks at how such images create new and powerful norms for urban life that transcend national boundaries. By walking Jakarta’s coast, we’ve engaged with how such norms are adopted and/or countered and deflected ‘on the ground’ in communities experiencing the brunt of rapid urban change. This research also explores what strategies are available to artists who seek to support communities subject to development programs and displacement.

Envisioning a global city

The marketing gallery at Pantai Indah Kapuk is one site where the elite aesthetic of this global city is disseminated. The gallery is a grand warehouse clad with marble, glass and chandeliers, used to promote the development projects of the Agung Sedayu Group who are responsible for the only artificial islands to have been built in Jakarta Bay to date: Golf Island and Riverwalk Island. The planned development for these islands was once promoted in the marketing gallery, but since Jakarta governor Anies Baswedan revoked the laws permitting land reclamation, the models have been in a dark room at the back of the building. Instead, developers promote Pantai Indah Kapuk 2 (PIK2), an elite new-town development on a substantial land bank in the coastal region of Tangerang.

Marketing gallery / Doyle & Ekin

The marketing gallery resembles a wealthy contemporary art museum, aiming to provide an immersive and stimulating experience of what the future holds. There are models, day-in-the-life animations of a happy family living at PIK2, drone videos of the development’s grandeur, and an audio-visual room reserved for large-scale investors. Developers go to great lengths to conjure a sense of wonder and optimism. Pak Hongky, one of the craftspeople responsible for the models at the gallery, explains the rationale for investing so much in aesthetics:

'Developers don’t lay out one cent of their own money. They get this capital from investors’ down-payments. The only capital they lay out is for images. These images makes consumers feel confident about investing in what is at that stage only a piece of empty land. It reassures them: ‘oh… it will look more or less like this’. An experienced developer will happily pay extra for a high-quality model.'

Since the traumatic experience of the Asian financial crisis in 1997, many of Indonesia’s developers use pre-sales to raise capital. Technologies such as models and animations are primarily used to promote yet-to-be-built developments and solicit investment. In the highly speculative environment of Indonesian real estate, images might be passed along by investors as a guarantee for a house that is bought and sold multiple times before it is built. These technologies also address a more general public, setting new standards of beauty and modernity against which all other forms of urban space are compared, and making a claim about what a desirable future for Jakarta should look and feel like.

Researchers in other post-colonial cities have shown how discourses of urban beauty often support the agendas of dominant elites. They point to how ideas of beauty, gleaned from circulating images of world-class cities, produce new and hegemonic aesthetic norms that resonate across societies. These norms have induced forms of self-government among those who identify with the desirability of these new standards. Asher Ghertner, writing of slum-dwellers facing eviction in Delhi, notes that ‘residents did not want to be displaced, but most understood and many even empathised with those who wanted them removed’. When asked what Delhi would look like in 10 years’ time, one slum-dweller responded ‘Delhi will be a beautiful city, totally neat and clean. All the slums will be removed and there will only be rich people’.

Beauty and control

Discourses of urban beauty often legitimise ‘spatial cleansing’. Abidin Kusno has described how an emergent middle-class environmentalism in Jakarta, and the rise of ‘green governance’, has seen ‘green imagery’ used to material and psychological affect, evicting poor communities to make space for parks and encouraging residents to assimilate their behaviour to the aesthetic norms of green governance. Ideas of beautification that conflate beauty with order can be turned into modes of control when they attract belief across a wide spectrum of society. Indeed, part of what has attracted our attention as artists and researchers is how the images of the Great Garuda Sea Wall compel Jakartans to consider the city’s north coast as a whole, and encourage them to feel that they have a stake in new urban projects that may not directly affect them.

Mangroves / Doyle & Ekin

However, having a stake in new urban projects that promise to improve the cities and nations people live in is fraught with danger for those whose lives and land are subject to this improvement. Because ideas of urban beauty are highly fluid, residents may participate in their own displacement by identifying with the desire for a city which has ‘transcended’ their settlements or ways of life. The new world-class aesthetic norms ushered in through projects such as the Great Garuda Sea Wall can turn beauty into control by devaluing or flattening other valid and diverse conceptions of beauty.

Bridge between PIK1 and Golf Island / Doyle & Ekin

On the bridge between the new town of Pantai Indah Kapuk and the first completed reclamation, Golf Island, residents from gritty neighbouring working class districts such as Kamal come to take selfies. They arrive on their motorbikes in the late afternoon, couples and families, framing themselves against the elegant curved spans of the bridge, the still-rising Gold Coast apartment complex, and the setting sun. How do we explain this practice? Are they identifying with the new aesthetic norms of a world-class city?

Resistance

The highly subjective quality of ideas of beauty means they can also signal alternative and sometimes-conflicting hopes, desires and value systems. In the fishing community of kampung Dadap, Tangerang, visible from the new bridge, the allure of the world-class city has not taken hold. A resident was shown a promotional image for PIK2: a riverside path framed by lush yet orderly vegetation; a young single-child family (a persistent theme of middle-class environmentalism); and shimmering residential complexes. They summed up a common sentiment within the kampung:

'What would I want with such a picture? What would I do in there? You tell me what I’m supposed to do in a place like that. When I see a picture like that, I know it’s meant to exclude people like us. And if I hung a picture like that in my home, the residents [of kampung Dadap] would say I was aspirational, that I want that sort of life as well.'

Doyle & Ekin

Dadap residents not only reject the image of the world-class city because it threatens to displace them, but also reject its status as a compelling vision of the future. Residents see the image of the world-class city as arbitrary, irrelevant, and environmentally ruinous. They are aware of the contradictions of the middle-class environmentalism that lauds the leafy residential areas of Pantai Indah Kapuk while describing the mangrove forests they were built upon as ‘wastelands’. Slums and mangroves are the two great pariahs of the world-class city, relentlessly targeted for improvement, which tends to mean elimination. But Dadap residents’ wholesale rejection of ‘world class aesthetics’ shows that in Jakarta at least, conceptions of urban beauty continue to animate other ideas of what ‘the good life’ is.

Jorgen Doyle (jorgendoyle@gmail.com) and Hannah Ekin (hannahmekin@gmail.com) are Australian artists and geographers who have just completed a six-month residency at the Rujak Centre for Urban Studies. In February of this year, together with Indonesian artists Irwan Ahmett and Tita Salina, they walked across Jakarta’s northern coastal region over 11 days and nights with the aim of producing situated knowledge through exploration.