Matthew Woolgar

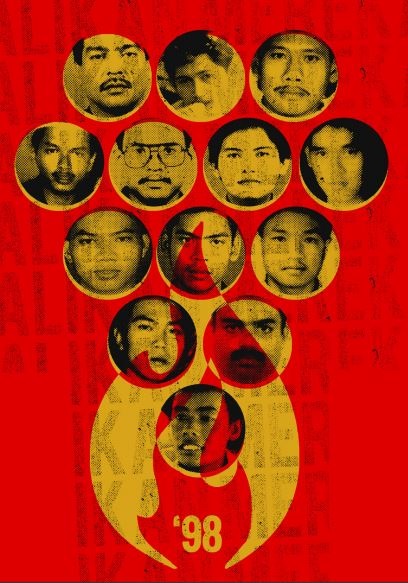

During 1997-98, Indonesian security forces abducted at least 20 pro-democracy activists and students. One was found stabbed to death. At least 13 of the others remain missing to this day and are presumed dead. Security forces eventually released the remaining abductees, most of whom were tortured whilst detained.

The security forces have themselves investigated these events, as have Komnas HAM (National Commission on Human Rights), the mass media and NGOs such as Kontras (Commission for the Disappeared and Victims of Violence). These investigations, as well as declassified reports from United States officials based in Jakarta, have provided important information on the abductions. However, many details surrounding their planning and implementation remain unclear.

A recently discovered report, circulated by the BIA (Military Intelligence Agency) in early 1998, adds further context. It highlights how the state security apparatus ratcheted up anti-communist paranoia just before the abduction of a number of activists linked to the left-wing PRD (Democratic People’s Party).

An evolving campaign of abductions

The abductions of 1997-98 occurred in three main waves: the first was from February to May 1997; the second from February to March 1998; and the last in May 1998. Each of the waves corresponded to a time of heightened political tension: the first period preceding national elections in May 1997; the second before and during an important session of the People's Consultative Assembly in March 1998; and the third at the peak of rioting in May 1998.

The affiliations of those abducted seem to reflect changing priorities on the part of the abductors. In the first half of 1997, authorities were concerned about the challenge posed by Megawati Sukarnoputri and a potential coalition of the PDI (Indonesian Democratic Party) and PPP (United Development Party) in the upcoming elections. Most of those abducted during that period had links to these two groups.

By contrast, many of those abducted in early 1998 had connections to the PRD or its student organisation, SMID (Indonesian Student Solidarity for Democracy). A bomb explosion in Tanah Tinggi, Jakarta, provided a pretext for the abductions; authorities claimed that this was part of a larger plot involving a bombing campaign orchestrated by the PRD as part of an unlikely alliance with a former general and a wealthy ethnic Chinese businessman.

Amid an increasingly repressive political climate, anti-communist paranoia provided further fuel for the abductions of early 1998, and helps to explain why the PRD with its small membership was disproportionately targeted. This paranoia tapped into the long history of anti-communist propaganda. Essential to the founding mythology of the New Order regime, anti-communism had been institutionalised in school curricula, national commemorations and a feature film. The ‘latent danger of communism’ – a phrase used frequently in New Order propaganda – could then be mobilised at moments of political tension. This had happened, for example, in 1996 when security forces imprisoned a number of PRD leaders on charges of subversion.

Opinion within the security services hardens

Despite the imprisonment of its leaders in 1996, the PRD had managed to maintain many of its networks. By early 1998 the view was growing within the security services that further action against the group was necessary.

A glimpse of this thinking is demonstrated by a BIA report circulated within the armed forces in late January 1998 – just weeks before the abduction of a number of activists linked to the PRD. The report argued that the state was still not vigilant enough about communism, and that further steps were needed to deal with the PRD threat. Although the report is vague about what precisely these ‘steps’ might entail, it gave a strong impression that something further needed to be done to meet the apparent danger.

The 97-page report, titled The Latent Communist Threat and the PRD as the Public Face of the Communist Underground in Indonesia, begins with the premise that communism ‘is a latent danger’ that ‘doesn’t know the word failure’. It then states the report’s intention to ‘uncover the PRD’s connections with underground communist organisations’ and former political prisoners.

The report provides a lengthy history of the PKI (Indonesian Communist Party), before drawing on what must have been pervasive state surveillance to describe a long list of student organisations and discussion groups starting from the 1970s. It also details activities of former political prisoners, attempting to link these to the students wherever possible. It then turns to the PRD, attempting to demonstrate the ‘red thread between the PKI and PRD’.

The conclusion of the report provides various recommendations. These include: ‘increasing inter-agency coordination and taking integrated steps in handling the latent danger of communism’ and ‘re-socialising vigilance against the danger of latent communism’.

One thread among many

Anti-communism was just one part of the context for the abductions of 1997-98. Members of the PRD and its affiliates were not the only victims of the abductions. Security forces had repeatedly shown a willingness to use violence against any perceived challenge to the regime.

The abductions also took place in a complex institutional context. A Military Honour Council found Prabowo Subianto, head of Kopassus (Special Forces) until late March 1998, culpable for some of the abductions, and a number of Kopassus soldiers were indeed court-martialled. However, media reporting drawing on sources within the armed forces indicated that elements from a range of army, police and intelligence bodies had been involved in the abductions. Moreover, it is unlikely Prabowo acted without the approval of seniors in the military command.

A 2006 Komnas HAM report aptly described the abduction of activists in 1997-98 as a ‘joint criminal enterprise’. Yet the lack of accountability to date is deeply troubling. Even the few people who faced some kind of sanction have continued to prosper. Prabowo has reinvented himself as a politician and presidential candidate, and many of the court-martialled soldiers have gone on to have successful careers in the military.

The anti-communist paranoia that helped to stoke the campaign of abductions is a reminder of deeper lineages to state-directed violence at the end of the New Order. One of those was the ‘red thread’ that ties the abduction of PRD-linked activists to the anti-communist propaganda that had been essential to the New Order regime since its inception.

Matthew Woolgar (matthew.woolgar@history.ox.ac.uk) is a PhD student at the University of Oxford, and is currently an academic visitor at the Australian National University. Any views expressed in this article are his own and do not represent the views of either institution.

Related Articles from II Archive

A day with Indonesia's radical student organisation by Vannessa Hearman

The slow birth of democracy by Munir

Still an age of activism by Ed Aspinall

Prabowo and human rights by Gerry van Klinken