Bilingual Chinese-Indonesian writer Wilson Tjandinegara built bridges within Indonesia’s literary culture

Josh Stenberg

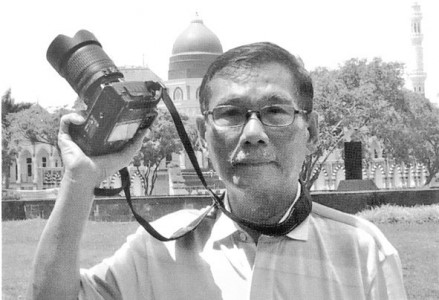

Last February many in the world of Indonesian letters were saddened to learn of the death in Makassar of Wilson Tjandinegara, also known in the Chinese world as Chen Donglong or 陳冬龍. Reminiscences appeared in the Chinese-language newspapers and magazines, and Wilson’s daughter made a visit to the Perhimpunan Penulis Tionghoa Indonesia (Chinese Indonesian Writers’ Association) to receive condolences and present a few of the writer’s effects. Few figures in our time have done more to draw together the Chinese-language communities of Indonesia and their counterparts in the broader Indonesian cultural world. From engagement with the culture of needy Hakka communities in Singkawang to his 2016 bilingual photobook Simfoni Keharmonisan (Symphony of Harmony, 和諧的旋律), Wilson was a generous and tireless bridge-builder, and a committed proponent of making and sustaining written Chinese as one among many Indonesian literary languages.

Unlike some of his generation, Wilson had not been active in the approved Chinese press of the New Order period, Harian Indonesia; nor did he seek to publish in Singapore, Hong Kong or mainland China, as some of his contemporaries did. Born to a Makassar tailor in 1946, Wilson received only a junior secondary education. As a young man, he was reportedly deeply impressed by Chairil Anwar’s poetry and became in literary matters an autodidact, no doubt drawing from knowledge he acquired partly through the bookshop he operated from 1970 to 1995. Indeed, his involvement in literary circles did not begin until he was nearing 50, just as Suharto’s era was showing signs of weakening and restrictions on Chinese cultural activities loosened. Joining the reviving Chinese literary associations at this time, he quickly made a name for himself in that small world as much for his outreach to the larger Indonesian literary and cultural community, as for his literary output in poetry, short prose, and translation.

Like most Chinese-language writers of Indonesia, Wilson was born outside of Java – in his case, Makassar – though he lived after 1995 in Tangerang. The centre of his literary activities were associations such as the Perhimpunan Penulis Tionghoa Indonesia (Sino-Indonesian Writers’ Association) and the Komunitas Sastra Indonesia (Indonesian Literature Community). Once he began publishing, he drew attention not least because of his willingness to treat national and international politics in his verse, including most famously the anti-Chinese riots of 1998 in such poems as ‘Kita Tak Boleh Diam Diri’ (We Must Not Keep Silent Anymore, 我們不能再沉默). This poem was included in his second collection, Rumah Panggung di Kampung Halaman (House in the Village, 故鄉的高脚屋, 1999), a volume which explores in both languages his homeland (and sometimes specifically Sulawesi) as well as his hopes for peaceful interethnic coexistence. His writing also had a pronounced romantic side, which he expressed in his translations of Chinese love poems and in his final poetry collection, Mengikuti Pilihan Hati (Pursuing the Heart’s Choice, 追尋心靈的選擇, 2007).

Besides publishing his own work in both languages, a volume of his translations of Tang poetry appeared in 2001, some of them rendering core classical Chinese works into Indonesian for the first time. His translating work also brought a selection of important local Chinese-language writing to broader attention in literary Indonesia. These local works include Lelaki Adalah Sebingkai lukisan (A Man is a Painting, 男人是一幅畫, 2001) by Jakarta author Yuan Ni (Jeanne L Yap, 袁霓) and Janji Berjumpa di Kota Pegunungan (Meeting in a Mountain Town, 相約在山城, 2001) by Bandung author Ming Fang (明芳), not to mention the poetry anthology Menyangga Dunia di atas Bulu Mata (Resting the World on Eyelashes, 1998) and work of short fiction Kumpulan Cerpen Mini Yin Hua (A Collection of Mini Sino-Indonesian Short Stories, 1999).

It seems appropriate to translate his 2005 poem ‘Note to Self' (自語). To the best of my knowledge, it is the first English translation of this prolific and committed translator’s own work.

‘Note to Self’

i’m a traveler in a rush

before night falls

i’ll make some headway

human life has its limits

literature is boundless

like a long-distance runner

in the final sprint

crossing the finish line

i have no time for

applause or boos

Wilson Tjandinegara’s earnest hope, declared a decade ago, was that even after the end of his life, his contribution to literature would endure. His twenty-odd volumes of poetry, prose, photography and translations will remain a major body of work at the intersection of Chinese and Indonesian literary languages.

Josh Stenberg is a lecturer in the Department of Chinese Studies at The University of Sydney. He thanks Pi Chen and Guoji Ribao for their assistance, and Sydney Southeast Asia Centre for its support.