The Jokowi government’s policy shift contributes to pervasive regulatory ambiguity in Indonesia’s mining sector

The global mining boom, occurring roughly between 2003 and 2013, caused a frenzy of mineral extraction across Indonesia’s resource-rich regions including Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Sumatra. During the boom years, Indonesia’s central and regional governments enjoyed a huge boost in revenues as demand from China sent commodity prices soaring. But many policy makers, activists and intellectuals were concerned that Indonesia’s finite resources were being shipped overseas too quickly and too cheaply, and that not enough Indonesians were feeling the economic benefits of the minerals boom.

In response, the government of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, or SBY, introduced a new mining law in 2009 which outlined a future ban on the export of raw mineral ores. The government’s goal was to kick-start a minerals processing industry by forcing companies to smelt their ores domestically. Indonesia could then move away from extracting and exporting cheap raw ore and, instead, produce and export higher value mineral products. This ban came into effect in January 2014.

The policy was primarily justified in nationalist terms. SBY and his cabinet described the ban as a way of achieving ‘economic sovereignty’. If Indonesia failed to invest now in a program for industrial upgrading, the government maintained, it would remain ‘a nation of slaves’. Without policies like the export ban, so the argument went, Indonesia would just continue selling cheap commodities to rich industrialised nations without ever moving up the global value chain.

After taking office in late 2014, Joko Widodo, or Jokowi, expressed strong support for the ban. Indeed, the broader agenda of downstream industrialisation aligned with the new president’s nationalist economic sensibilities. But then, in January 2017, Jokowi changed his mind. His government reversed the ban, jeopardising three years of downstream investment and development. This article briefly maps the life and death of Indonesia’s mineral export ban. It explains how the ban came about, the results it achieved and why it was revoked. It also offers some reflections on what the ban reveals about the nature of resource nationalism in Indonesia. I emphasise Jokowi’s particularly statist brand of economic nationalism in comparison to his predecessor, and highlight the intractable regulatory ambiguity that has come to characterise the governance of Indonesia’s resource sectors.

The life of the ban

The 2009 Mining Law laid the legal foundation for the 2014 export ban. Articles 102 and 103 of the law mandate that companies must add value to mineral ores prior to export. Article 170 stipulated that companies with contracts of work or mining licenses had five years from the law’s enactment in which to prepare processing facilities. After the January 2014 deadline, the government would ban raw mineral exports, and only minerals at specified purity levels would be allowed to leave Indonesian shores.

By 2014, however, the global minerals boom was over. Indonesia’s economy was slowing, and the current account deficit was at its worst since 1986. In the years following the law’s enactment both foreign and domestic companies failed to invest in mineral smelters, not believing the government would introduce a hard ban and sacrifice lucrative export revenues. This meant that by 2014 Indonesia still had virtually no refining capacity for key minerals like nickel, bauxite or copper. Most industry stakeholders assumed the government would re-think the intervention and retreat from the nationalist position.

President SBY outlined plans for the ban in the 2009 mining law, hoping to kick-start Indonesia's minerals processing industry. It was in full effect from 2014 to 2017. (US Department of State)

But the government went ahead, and in January 2014 it introduced a hard ban on the export of nickel and bauxite. The intervention shocked the domestic and international mining industry. Nickel and bauxite mining came to a virtual standstill, which the government understood would cut exports by approximately US$4 billion in the first year. (Copper, however, was given a last-minute reprieve.) But despite the immediate economic pain, the SBY government remained committed to what it regarded as a long-term plan for industrialising Indonesia’s resource economy. Some observers also speculated that senior political and business figures with potential downstream investments pushed the policy over the line – but those claims remain unsubstantiated.

The policy did begin to pay off in the years that followed. The downstream sector attracted billions of dollars in investment, and the volume of refined nickel began to increase. Most of the capital came from China, with investors sometimes partnering up with local companies in joint ventures. So, despite widespread condemnation from industry analysts, Indonesia’s ban appeared to be doing its job, developing Indonesia’s downstream capacity and pushing it up the global value chain.

The death of the ban

So why did Jokowi reverse the ban in 2017? A new regulation introduced in January allows exports to resume under certain conditions. When the new president took office the boom was over and Jokowi was tasked with managing a growing trade deficit. Yet he and his cabinet initially came out in strong support of the export ban. And, given that investment was beginning to produce results, the consensus among industry analysts and government officials was that Jokowi would stick to the plan for downstream industrialisation. One explanation paints the relaxation as the government’s response to financial pressures because opening the door to exports would help ease the budget deficit even if the contribution would be relatively small overall.

But a second theory looks more compelling. Prior to the ban, state-owned company PT Aneka Tambang (Antam) exported the largest proportion of Indonesia’s raw nickel ore. (Brazil’s Vale is the largest nickel company in Indonesia but it already processes its nickel ores domestically.) This meant that Antam suffered huge financial losses when the nickel ban was introduced. Back in 2014, the consensus among policy makers was that Antam would have to suffer immediate financial pain in order to eventually become a driver of value-added economic growth. Unable to export, and with no smelter to sell to, Antam’s profits nosedived – it booked Rp.743 billion in losses in 2014. In 2015 the Jokowi government poured Rp.7 trillion into Antam in order to boost the company’s output and help it invest in several downstream projects.

Industry insiders suggested that the government’s decision to relax the ban was more about fixing Antam’s bottom line than about fixing broader budget troubles. Indeed, in the lead up to the January 2017 smelter deadline, there were rumours that the ban would be relaxed for Antam only and not for Indonesia’s hundreds of smaller domestic nickel exporters. When the relaxation was announced, Antam’s shares jumped six per cent.

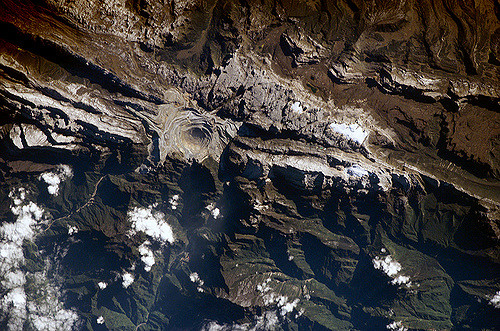

This theory makes sense when viewed in the context of Jokowi’s broader vision for the mining sector. Rini Soemarno, Minister for State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), has outlined a plan to consolidate SOEs under a new state-run mining holding company (a reformed version of PT Inalum, the state’s aluminium miner). A holding company with a diverse portfolio of assets can attract more capital, giving it the capacity to acquire shares in expensive and lucrative privately run mines. The government’s target is clearly PT Freeport Indonesia, the subsidiary of Freeport McMoRan, which is currently engaged in difficult negotiations with the government over divestment obligations. Reversing the ban would help Antam’s profits to rebound, thus putting Antam, and therefore the planned holding company, in a better financial position to take over foreign-operated mining projects like Freeport’s Grasberg mine. For Jokowi, strengthening Indonesia’s state-owned enterprises and their control over the industry took precedence over private, mostly foreign, downstream investment.

Some have theorised that the ban reverse was aimed at helping Antam take over foreign mining projects, like the Grasberg mine currently operated by Freeport. (SkyTruth)

In pursuit of state-led industrialisation

What does the life and death of the export ban tell us about the nature of resource nationalism in Indonesia? First, we can see that Jokowi’s resource nationalism has a more statist orientation than his predecessor’s. Jokowi is more committed to reforming and expanding the state sector, and he wants state capital to play a prominent role in the extraction, production and industrialisation of Indonesia’s resources. One might speculate as to whether this approach is designed to counterbalance the expansion of politico-business elites into Indonesia’s lucrative extractive sectors at a time when more and more foreign companies are leaving.

Second, this case illustrates the challenges of executing an industrial strategy in a country where laws and regulations are so mutable. Nationalist mobilisation in Indonesia has, in many instances, not produced a coherently nationalist regulatory regime. Instead, it has given rise to inscrutable regulatory and institutional ambiguity as rules are constantly renegotiated, revised and retracted. While many within Indonesia’s political and policy elite might share a developmentalist vision for state-led industrialisation, the institutional ingredients are missing. Without an autonomous policy making class, industrial policy can easily be changed to serve the, often short-term, personal or political goals of Indonesian politicians.

A longer version of this paper was presented at the 2017 Indonesia Update Conference, Indonesia in the New World: Globalisation, Nationalism and Sovereignty, and will appear in the forthcoming book publication.

Eve Warburton (eve.warburton@anu.edu.au) is a PhD candidate in the Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs at the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific.