Elsa Clave and Andy Fuller

The 1965 mass killings of suspected communists has long cast a shadow over Indonesia. Despite a growing movement of reconciliation activists who seek to redeem the position of victims into everyday life, the Indonesian nation has not come to terms with the role played by the state in the killings that left hundreds of thousands dead, imprisoned or deeply traumatised. Many people in positions of power regard this aspect of Indonesia’s history to be finished and in the distant past. But that is not the case for the victims and survivors of the mass killings.

In 2003 the National Commission for Human Rights (Komnas HAM) conducted research on human rights violations under Suharto but due to the political situation, the report was produced only nine years later. Since 2012 bureaucratic stalling has blocked the judicial process which should have followed. The International People’s Tribunal (IPT) 1965 was formed to urge the state to continue what was started with the Komnas HAM report.

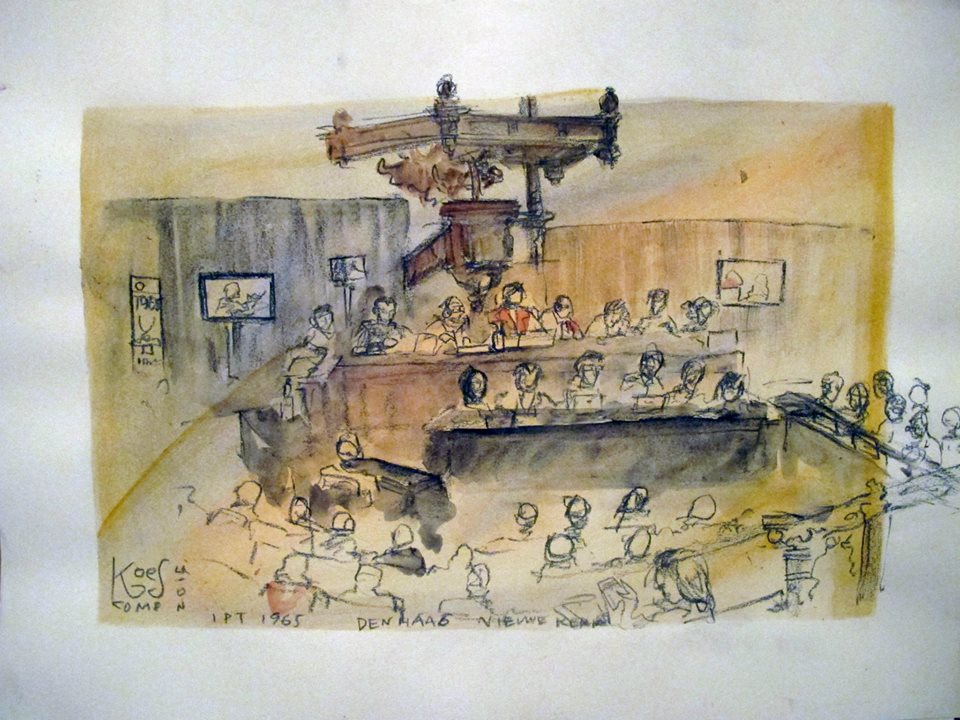

For four days, from 10 to 13 November 2015, in Nieuwe Kerk, The Hague, the IPT 1965 heard testimony from survivors, researchers and legal experts before an international panel of judges. The IPT 1965 was criticised by Indonesian officials and activists as being a foreign intervention in the sacred domain of Indonesian history and law, but it was an important step in the path to reconciliation and giving a voice to survivors.

Many months later, on 20 July 2016, following months of deliberation it released its official verdict. The judgement accepted that crimes against humanity had occurred based on the nine counts presented by the prosecution.

An eyewitness account of the Tribunal

The IPT opened on 10 November 2015 – a symbolic date in Indonesia commemorating National Heroes Day. We were both present in the public gallery to witness the tribunal over these four days.

On day one the prosecution presented the charges of mass murder and enslavement; on day two, imprisonment, torture and sexual violence; day three, persecution, enforced disappearances and hate crimes-propaganda; and day four, complicity of other states. These were the nine charges presented to the court. Witnesses explained the mechanism of the Indonesian state, while slowly and calmly, victims explained what had happened to them. It became evident that for those testifying, the tribunal was not only about seeking justice, but also about trying to understand why this onslaught of violence and hate had befallen them, the ramifications of which were still being felt now. Incomprehension is certainly as haunting as feelings of injustice.

Each day layers of the horror for the victims were revealed. On the first day, historian Asvi Warman Adam presented details about the concentration camp on Buru Island where 11,600 people were imprisoned between 1969 and 1979. These prisoners were detained as victims for many years without trial and moved from the prisons of the archipelago to the remote camp where they were officially stamped as ‘category B’ prisoners. He showed there was a clear chain of command from the attorney general to the general of the Operational Command for the Restoration of Order and Security (Kopkamtib) and down to the lower ranks.

Bedjo Untung, head of the Yayasan Penelitian Korban Pembunuhan 1965/66 (YPKP65: Foundation for Research into Victims of the Killings of 1965-66), recounted his story of imprisonment for the Tribunal. Pak Bedjo was first arrested when he was a student in 1965 and after five years of escaping and hiding, was detained again during Operasi Kalong (Operation Bat), a campaign led by the military in the late 1960s. During his unlawful detention Pak Bedjo was electrocuted and starved, fed only a mixture of rice and sand. Five of his fellow prisoners died during the first year and one committed suicide. He implored, ‘And now, I ask for the State to take responsibility. Why was I arrested?’

The hearings on sexual violence were particularly graphic and disturbing. The harrowing and detailed testimonials of Tintin Rahayu (a pseudonym) were given from behind a black curtain, with an assistant sitting alongside her as she spoke. A student member of the Perhimpunan Mahasiswa Katolik Republik Indonesia (PMKRI: Catholic Students Association) and the daughter of a dalang (puppeteer), Tintin was imprisoned for 11 years. She gave testimony of how she was repeatedly raped, had her genitals burnt and was beaten unconscious with a bicycle. In the courtroom, many were on the brink of tears. Her voice wavered before she yelled the name of the man who tortured her the most: Lukman Soetrisno, a respected professor at the prominent University of Gajah Mada. Rather than being punished, the perpetrators of these crimes lived respectfully and prosperously throughout the New Order.

Two respected historians, Wijaya Herlambang and Bradley Simpson, detailed the complicity of other nations in the mass killings. Simpson told how a British covert operation in 1963-1965, was aimed at stirring up dissension between factions inside Indonesia. Edward Peck, the assistant under-secretary of State in the Foreign Office at the time, was encouraging of a premature PKI coup during Sukarno’s era. Wijaya and Simpson were at pains to emphasise that although the crimes were committed in Indonesia, other countries including the UK, the USA and Australia, played a role in facilitating, encouraging and covering them up.

On each day of the Tribunal a court administrator asked perfunctorily if a member of the Indonesian government was in attendance. On each morning, the question was met with silence. The lack of an opponent, however, did not mean it was entirely smooth sailing for the prosecution team and its witnesses. Chief prosecutor, Todung Mulya Lubis, so often a singularly powerful and strident voice, tested by the judges’ probing questions, responded with caution and some nervousness at the gravity of the subject matter.

Judge Yacoob, a veteran of trials against the criminals of South Africa’s apartheid, was not to be messed with or to be left wondering in the prosecution of this case. For the trial to reach its conclusion within the limited time available, administration was necessarily disciplined. And yet, despite the gravity of the daily events there were moments of humour; and despite their grilling, victims and witnesses too, were addressed respectfully as the judges were fully aware of the risks that many were taking by even being there.

The closure of the IPT was marked with a small ceremony to remember those who died. Candles, music and words on ruban papers were arranged on an improvised altar. Adi Rukun, the protagonist in the documentary feature film directed by American Joshua Oppenheimer, The Look of Silence, sent a statement, which was read out:

“We have no power in our own country. We’re abused and insulted and always under suspicion. We’re intimidated. We’ve been finished off. We’re treated like rubbish. We’re considered to be useless and not to be fully human – people think we’re wicked. But, we’re real human beings. We feel just like other people. Isn’t 50 years of suffering enough? Do we have to be guilty for something that we didn’t do? Do we have to wait another thousand years before we can be considered to be human? Aren’t you all tired of torturing us? You have taken all that we have: our belongings, our freedom, the purity of our mothers, our respect. We don’t have anything left – except for making our statements here at this IPT. Thank you and my respect to the Judge and the other witnesses at this IPT.”

At the end of the fourth day of hearings and in his later report of findings, Judge Yacoob stated plainly that there was no doubt that the 1965-66 mass killings against suspected or accused communists did happen. The victims were vindicated. The case was based on testimonies pertaining to mass killings, imprisonment, torture, sexual violence and the complicity of other states – the USA, the UK and Australia.

As mainstream politicians in Indonesia ignored and disparaged the Tribunal, at press conferences before, during and afterwards, Todung Mulya Lubis declared that it had no legal standing but rather a moral force that it was hoped could lead to change.

Approaching reconciliation

This IPT itself and its subsequent findings and recommendations were not met with unanimous support among the community of survivors of 1965. Some 1965 activists questioned the effectiveness of an international initiative, suggesting that it could it in fact be detrimental to the lives or situations of activists in Indonesia.

Some groups prefer to approach reconciliation among their neighbours within their local community. In 2003 an organisation established by members of the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), the Syarikat Masyarakat Santri Untuk Advokasi Rakyat, arranged meetings between victims and perpetrators, at which they admitted the responsibility of the NU in mass killings. Other events have addressed the need to remember and write this part of Indonesian history beyond dates, politics and the numbers of dead.

The Yogyakarta-based Museum Bergerak initiated a collection of the belongings of victims, in order to narrate a forgotten story with images, and to call for the third generation to remember and understand this tragic period. This is the same impulse which animates the events held in Sanata Dharma organised by Romo Baskara Wardaya. In September 2016, the Dialita choir performed for staff and students of the university. Women who were victims, friends or relatives sang their experience and pain in front of more than 300 people. ‘Dunia milik kita’ (The world is ours), they said, hoping their will would be turned into reality by those words.

But for others, compassion and remembrance alone will not bring longed-for reconciliation at the grassroots level and an end to stigmatisation. A due judicial process is needed to avoid the repetition of impunity.

In his closing remarks to the IPT, Judge Yacoob stressed that it should be in the Indonesian government’s utmost interest to adequately deal with the ongoing injustices perpetrated against the victims of 1965. Reform in Indonesia has not led to a re-conception of the official discourse about 1965, nor an official apology.

The IPT 1965 does not see itself as a substitution for the judicial process that must take place in Indonesia. It has embarked on a campaign of socialisation in Indonesia, in preparation for the next step which could reach its conclusion at the United Nations.

However, these efforts could bear conflicting results if national and international initiatives continue to work in parallel. One of the victims pointed out that the term ‘korban enam puluh lima’ (’65 victim) is inappropriate: they continue to be victims up until now. The reality for victims remains precarious and subject to the populist preaching of politicians who seek to gain legitimacy through some easy provocations made against an ever-present ‘communist threat’ articulated today as ‘new style of communism’.

Elsa Clave is junior professor in Southeast Asian History at Goethe University, Frankfurt.

Andy Fuller (fuller.andy@gmail.com) is honorary fellow at the Asia Institute, the University of Melbourne.

The Final Report of the International People's Tribunal on Crimes Against Humanity in Indonesia 1965 (Laporan Akhir Pengadilan Rakyat Internasional 1965) is available for purchase here.