Reviewing the history behind and themes in Hanung Bramantyo's Kartini

Reviewing the history behind and themes in Hanung Bramantyo's Kartini

Following the Melbourne screening of Hanung Bramantyo’s new film Kartini in May 2017, the University of Melbourne’s Indonesia Forum organised a symposium on the theme ‘The film Kartini and Kartini as a source of historical and contemporary inspiration in Indonesia’. Four speakers were invited to present their responses based on their particular areas of research. Here they briefly re-present their takes on director Hanung’s latest cinematic interpretation of Indonesia’s iconic female national hero.

The Kartini film’s portrayal of Javanese culture

Helen Pausacker

Caged perkutut birds (known as ‘zebra doves’ or ‘turtle doves’) provide a leitmotif in the film, Kartini. Javanese nobility kept these highly prized birds, which were appreciated both for their beauty and also for their song. The perkutut can be seen as a metaphor for the ‘caged’ noblewomen.

The film portrays the patriarchal and highly stratified nature of Javanese culture in the late nineteenth century. Although the elite had power, this power was largely in the hands of men and the film demonstrates a number of customs and traditions which oppressed women. In doing so, the film remained reasonably faithful to Kartini’s diaries.

The first of these oppressive customs was pingitan, the custom of secluding women after their first menstruation, until they were married. While some elite Javanese women received primary education, this would cease on pingitan. Kartini was from a more ‘progressive’ family than many at the time and was allowed to continue her education with a private teacher, until she and her sisters were eventually released from pingitan.

The second custom portrayed in the film was that of arranged marriages. The early twentieth century led to a demand for love matches throughout the archipelago of the Dutch East Indies. This became a popular theme of literature, one example being Sitti Nurbaya by Marah Rusli (1922). Kartini was, at least technically, permitted to reject the marriage proposal made to her, although she experienced heavy family pressure and felt a strong sense of obligation.

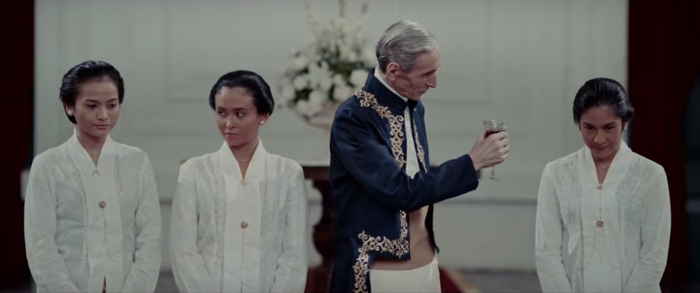

The third oppressive institution portrayed was polygamy, the film depicting the great difference in status between wife number one (the Raden Ayu) and the others. The film also showed that while this primarily oppressed women, men also experienced the weight of societal expectation, albeit less than women. Kartini’s father, for example, had first married Kartini’s birth mother but was pressured into marrying a woman with a higher status as his Raden Ayu, when he rose in rank.

The hierarchy of both class and age in Javanese society at the time is also demonstrated in the film through laku dhodhok (squatting walk) and sembah (raising hands in front of face in a prayer-like gesture), both of which demonstrate respect for a superior. By interspersing Javanese with Indonesian in the film, the film was also able to demonstrate the hierarchical relationships, even between siblings, with High Javanese being spoken to older people or those of higher status. The film also shows how Kartini rebelled against this in her relationships with her own younger siblings.

Some aspects of the film, however, seemed more appropriate to a modern sinetron (soapie) than a late nineteenth to /early twentieth century court. There seemed to be an excessive amount of loud sobbing. It was also hard to imagine even progressive noblewomen climbing up and sitting on a wall, or frolicking in the ocean. Ending the film with Kartini accepting her future husband’s marriage proposal, rather than with her death in childbirth in a polygamous marriage, seemed an attempt to create an unreal ‘happy ending’. In balance, however, the film was successful in recreating the spirit of the times.

|

|

Film still. (Legacy Pictures) |

Notes from Kartini

Dina Afrianty

Kartini’s messages are still of relevance for contemporary women’s activism in Indonesia today. Indonesian women are still struggling for equal opportunity in education, fighting against the practice of child marriage and defining their role and status both in private and public spaces. They are still challenging patriarchal and feudalistic traditions mostly derived from conservative and orthodox interpretations of religion –, in this case, Islam, the religion of the majority of Indonesians.

Hanung Bramantyo’s film depicts Kartini’s inspiration for fighting for equality as largely originating from her interaction with her brother who studied in the Netherlands, and her connection with her father’s Dutch friends, who opened up for her an opportunity to connect and communicate with Dutch friends of her own. Like Kartini, Indonesia’s women’s activism has always been inspired by the global women’s movements.

The film shows us that apart from her exposure to western culture, Kartini learned that Islamic teachings do not discriminate against women, as men and women are equally required to acquire knowledge. Born into a Muslim family, as a child she rebelled and refused to take part in Qur’an classes. It was only later that she understood that men and women have the same rights to education. The film shows her learning from a visiting kyai that both boys and girls are required to read the Qur’an and importantly, about the need for all Muslims to understand its real message.

Kartini was concerned that the teachings in the Qur’an could not be truly understood by all Muslims, because it was available only in Arabic. The necessity of a translation in order to spread greater understanding of the Qur’an has continued to be an important theme in Indonesia’s women’s activism. Following the path of Islamic feminism in many Muslim societies, Indonesian feminists both secular and religious believe that one way of challenging patriarchal tradition is by promoting the need for rereading and reinterpreting the Qur’an.

Polygamy is a topic of particular importance in Indonesian women’s struggle for justice and equality. For feminist and women’s rights activists the story of Kartini’s obligation to follow her parents’ request that she marry a man who already had three wives, is used in this film and elsewhere to inspire women to fight against polygamy; to understand that polygamy is bad for women and that it is nothing more than an old tradition. Moderate Muslim scholars and women’s activists have challenged the way the verses of the Qur’an are used to justify polygamy.

In recent years, however, with the rise of religious conservatism we see this story being used for a different purpose. The story of Kartini as a fourth wife and the daughter of a polygamous father is used by conservatives to justify and promote polygamy. Even Kartini, who was smart and independent and fought for emancipation, they argue, ended up living in a polygamous marriage. Conservatives have used the story of Kartini to criticise the feminist struggle and women’s activism. They claim that Kartini was the exemplary pious Muslim woman because she followed the path of Prophet’s Muhammad’s wives who accepted living in a polygamous marriage.

|

|

Film still. (Legacy Pictures) |

The construction of masculinity and femininity in Kartini

Hani Yulindrasari

Hanung Bramantyo’s film depicts the traditional version of masculinity and femininity of the priyayi (Javanese aristocratic) class, with rituals and rules about how to speak, behave and interact with others according to class and gender. However, director Hanung has also successfully portrayed the complexities of masculinity and femininity within this class, between the ideal and what is practiced.

The film begins with Kartini performing a key element of priyayi femininity, marking her submission and obedience to the power of her Romo (father). She squat walks (laku ndhodhok) towards him and sits on the floor whilst her Romo sits on a chair. She keeps her head down and does not dare to look into her Romo’s eyes while talking. The traditional priyayi construction of gender places the supremacy of power in the hands of a dominant male. Daughters, sons, and wives must submit to the father’s will. A daughter also has to obey the mother and her brothers.

In the course of the film, however, Hanung Bramantyo shows us how Kartini challenges this imposed form of femininity to enact a freer and ‘masculine’ form. Hanung shows how Kartini sits cross-legged (duduk bersila) – a traditional Javanese men’s way of sitting – climbs a ladder, and laughs out loud. This is male-type behaviour, free of the constraints traditionally imposed on priyayi women. Kartini also subtly negotiates and challenges the tradition of pingitan (seclusion), including through her writings, eventually convincing her father to allow her and her sisters to emerge out of their seclusion and into the outside world.

Kartini is also shown to be aware that the restrictions imposed on her relate not only to her gender but also to her class. When she says, ‘I want to be common people’, she not only implies an egalitarian value but also her awareness of the entanglement of class and gender in the oppression of women.

Hanung portrays hegemonic masculinity as a cultural product that limits men, as well as women. A respectful man has to follow a normative ideal and is pressured to conform to this hegemonic construction. It becomes clear when the Romo asks Kartini’s sister Kardinah to accept a marriage proposal and admits, ‘I have promised him (the husband-to-be), and a respectful man has to keep his promises.’. Throughout the film he is shown having to enforce – reluctantly – polygamy by marrying his noble wife to preserve power in his family line. The film also shows how her brothers, firstly Kartono but in the end also her oldest brother, Busono, come to respect Kartini’s views and give up their male power. Even her husband-to-be, while remaining polygamous, at least comes to accept Kartini’s list of conditions.

Whilst access to education and economic and political resources is relatively better today than in Kartini’s time, her experience is not dramatically different from women’s contemporary experience in Indonesia. There are still dominant ideals of femininity and masculinity held by different social groups, which women and men are pressured to submit to. At the same time, new constructions of femininity projecting women as strong, educated, powerful and successful, both in family and career, bring new pressures to contemporary Indonesian women. Like Kartini, women in Indonesia are continualously struggleing to achieve their aspirations and dreams, in negotiation with the demands of ideal femininity. Like Kartini’s father and older brothers, Indonesian men also need to challenge and negotiate the idea of hegemonic masculinity in pursuit of gender equality.

|

|

Film still. (Legacy Pictures) |

Seeing Hanung Bramantyo’s ‘Kartini’ in the light of the historical sources

Joost Coté

Hanung Bramantyo’s film, Kartini provides a fresh look at this important historical figure in Indonesian history. It provides contemporary audiences with a believable insight into how each member of this Javanese priyayi family responded to the challenges that Kartini introduced. Central to Hanung’s sensitive interpretation is the issue also central in Kartini’s correspondence: polygamy, and the tradition-defined future then available to women of her class, which Kartini challenged. This dramatically refocuses the conventional emphasis on her association with education, which is only briefly and in terms of historical chronology, incorrectly, referred to in the film.

Director Hanung has to be congratulated for the way he has bravely cut a path through the long tradition of ‘Kartini interpretations’ as well as the many historical issues embedded in the original Kartini correspondence, in order to present a coherent and engaging story. It is therefore worth briefly indicating what the director decided to highlight, what he chose to ignore and what, I would venture to say, is historically misleading in the film.

Among the historical ‘facts’ highlighted in the film was the emphasis given to Kartini’s work with the Jepara woodcraftsman, which may well have been influenced by the director’s visit to Rumah Kartini. This is a small band of enthusiasts in Jepara currently revitalising local Kartini-era wood carving and batik crafts. As the film shows, it was Kartini’s role as intermediary between craftsman and European craft enthusiasts that contributed to bringing Kartini to European attention. Equally interesting, is the attention given to the publication of Kartini’s major ethnographic article – and hints concerning her other publications.

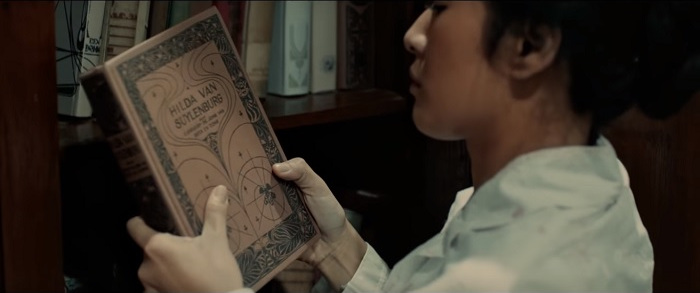

Another less-often discussed, but here highlighted, historical aspect is the responses of her brothers, Sosrokartono and Busono, and her older sister Sulastri. The latter two are ‘traditionalists’ who eventually come to accept Kartini’s progressive views. Kartono, however, while an important influence and possibly also mentor, was not the one who introduced Kartini to Dutch feminist literature. That came from the wife of the local Dutch colonial official, accurately defined in the film as a feminist and author, and later also via other European feminist correspondents.

In this context it is worth noting the film’s portrayal of Europeans. Generally the film presents them in a positive light but in the case of the two political figures, the socialist parliamentarian Henry van Kol and the colonial director of education, Jacques Abendanon, their important role in supporting her study plans are understated. The portrayal of ‘Oom Piet’, the elderly colonial resident of Semarang, more clearly reflects Kartini opinion: while he was impressed by her abilities, he was also ‘a bit creepy’. He is on record as officially refusing to support her plans to study in the Netherlands.

There is also no historical evidence that Kartini specifically spoke to a Kyai in the terms portrayed in the film: what is clear from her correspondence, however is that Kartini did come to reconcile herself with a modernising Islam after rebelling against her traditional Islamic education as a child.

Given how the director shapes the film to work toward a climax – Kartini’s betrothal to a polygamous widower – the emphasis the film gives to the set of conditions Kartini sets down before agreeing to the marriage, with the approval of her father, is an important one. This is (almost) as reported in the correspondence, except that the film version does not include the condition that she would be allowed to continue studying. What the director consciously omits (because it would muddy the perfect narrative perhaps?) is the last year of Kartini’s life and her tragic death.

This historical nitpicking, however, should not detract from enjoyment of this excellent piece of cinema, which hopefully will encourage viewers to refresh their appreciation of this brave and inspiring woman.

|

Hanung Bramantyo, Kartini. Legacy Pictures, 2017.

|

Helen Pausacker (h.pausacker@unimelb.edu.au) is Deputy Director of the Centre for Indonesian Law, Islam and Society at the University of Melbourne. She is co-editor (with Tim Lindsey) of Religion, Law and Intolerance in Indonesia (Routledge, 2016).

Dina Afrianty (Dina.Afrianty@acu.edu.au) is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Institute for Religion, Politics, and Society (IRPS) at the Australian Catholic University. She is the author of Women and Sharia Law in Indonesia: Local Women’s NGOs and the reform of Islamic Law in Aceh (Routledge, 2015).

Hani Yulindrasari (hani.yulindrasari@unimelb.edu.au) is a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne. She is researching masculinities in Indonesian early childhood education.

Joost Coté (joost.cote@monash.edu) is a senior research fellow at SOPHIS, Monash University. He has published several edited and annotated volumes of his English translations of the letters of Kartini and her sisters, including Kartini, The Complete Writings 1898-1904 (Monash University Publishing, 2014) and Realising the Dream of RA Kartini: Her Sisters’ Letters from Colonial Java (Ohio University Press, 2008).

Related articles from the archive

|

Jun 19, 2017 |

|

|

Dec 08, 2015 |

|

|

Oct 12, 2015 |