Contemporary Indonesian painter Mahdi Abdullah exhibits Acehnese culture in Melbourne

Transmemorabilia, an exhibition by Acehnese-born artist Mahdi Abdullah, was presented in 2016 at Monash University's MADA Gallery as part of the International Conference and Cultural Event (ICCE) of Aceh organised by ethnomusicologists Professor Margaret Kartomi and Dr Ari Palawi. ICCE also included a festival of films by young Acehnese filmmakers, an exhibition of Acehnese material culture presented by the Music Archive of Monash University (MAMU), and performances by visiting Acehnese dancers and musicians. These events attracted large numbers of viewers to the two-week exhibition.

For more than a century, generations of Acehnese people have suffered through conflict. The battles against Dutch occupation were particularly harsh in Aceh. This was followed by the Japanese invasion and internal conflicts that arose after World War II. Conflict raged again when Aceh's struggle for independence from Indonesia started in 1976. For decades, Gerakan Aceh Merdeka (GAM, or the Free Aceh Movement) fought against the Indonesian military, and most outsiders were prohibited from visiting the province – that is, until the more recent tragedy.

The Boxing Day tsunami that occurred on 26 December 2004 killed an estimated 180,000 people in Aceh province alone. The Acehnese suffered further losses not only of human life but also many aspects of their culture. The negotiation of a peace accord in Helsinki between GAM and the Indonesian government enabled the post-tsunami reconstruction to begin.

Mahdi Abdullah has endured some of the Acehnese people’s pain, fear and loss throughout his lifetime. Born on 26 June 1960 in Banda Aceh, the multi-award winning artist now lives in Yogyakarta, and is involved with the Arts Institute of Indonesia. He returns to his home province whenever he can, however, and paints his response to the expressions of suffering in the faces of the poor, in particular of women and the elderly. His artworks force the viewer to reflect on the sustained terror inflicted on the Acehnese during the protracted wars and tragic 2004 tsunami. They send a powerful message: that terror has gradually led to a diminished humanity and the loss of a clear sense of Acehnese identity. In place of this terror, Mahdi’s paintings offer a welcome vision of peace, one that seeks to contribute to the restoration of hope and dignity.

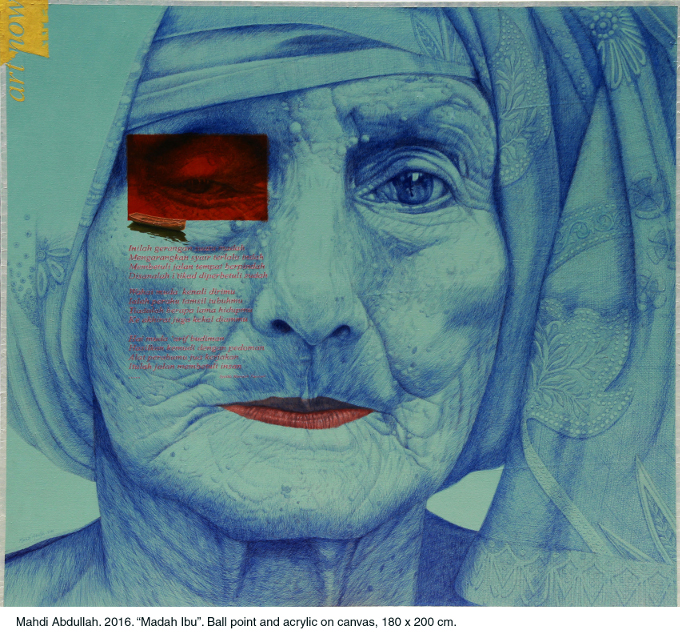

In his painting titled Madah Ibu (Mother’s Words), Mahdi’s original technique combines the materials of acrylic paint and ballpoint pen. A larger than life image of an Acehnese grandmother’s face with a headscarf covering her hair fills the 1.8 by 2-metre canvas. Painted in various shades of blue, the fine lines of her face drawn in blue ballpoint pen took months to complete.

When asked why he often painted women’s faces, he said, ‘I’m always keen to understand the history that lies behind the wrinkles on women’s faces, particularly those of older women, and then to draw them’. In the woman’s expression in this painting, Mahdi sought to portray her wisdom and the memories of hardship and pain that she and her fellow Acehnese have endured over many years. Mahdi says he draws his inspiration from the culture and the community generally; on the one hand from the people’s struggle to survive, and from their frequent experience of gunfire and explosions on the other.

|

|

Supplied by author. (Mahdi Abdullah) |

A tiny rifle-shaped gun is visible just beneath the pupil of her right eye. For Mahdi, the traumas of war and the violence committed by both sides in the conflicts are represented by the weapons that are common in his paintings. These weapons allude to the thousands of pieces of ammunition found scattered throughout the province. The paintings also comment on the spirit and the struggle of the people. He asks the viewer to consider the consequences of the longstanding armed conflict in Aceh. His paintings suggest that such political conflicts have been, and could continue to be, the main cause of the demise of the province’s social and cultural fabric.

If we scan the rest of the work, we realise that the woman’s face forms a blue background to the main focal points that are painted in red: her right eye, her lips, and the words of well known poet Hamza Fansuri in Mahdi’s hand writing.

The red transparent square placed over the woman’s right eye, according to Mahdi, suggests haziness, for the people’s vision is often blurry, he says, and those who do good deeds and say good things are rarely seen or acknowledged.

A small boat is drawn just beneath the woman’s eye. It refers to the title of the poem, Syair Perahu (Boat Poem), the final two stanzas of which call us to take charge of our relatively short lives.

Mixed media, realism, surrealism

Mahdi’s mixed-media approach incorporates a combination of acrylic and oil paints, charcoal, pastels, colour pencils and ballpoint pens. The type of tusir (rendering) used in Madah Ibu, described above, is achieved by mixing ballpoint pen with acrylic paint. In this painting Mahdi’s style is representational and realistic. Untitled (2011), however, borders on the surreal. Its design was based on an earlier lithography, Apollo and Soyuz (2009), which depicts an aerial view of a peaceful beach scene with the faces of a man and a woman kissing.

Indeed stylistically he juxtaposes elements in unexpected ways; in this case, the bodies of the kissing man and woman each lie in flight inside gold-coloured, enlarged bullets, one of which contains a pile of tiny human skulls. The bullets are on a collision course, bound for each other. What we witness in the image is a beach scene in the tranquil moment just before the violent impact of the two bullets hitting their targets.

|

|

Supplied by author. (Mahdi Abdullah) |

Character studies as social commentary

Many of the human figures in Mahdi’s paintings are character studies, based on photographs he has taken of Acehnese people going about their daily lives. Through direct observation he often paints life-like figures and objects, such as women carrying baskets of fruit on their heads, old bullets and other arms that continue to be found buried or in waterways, and farmers and fishermen working in the fields or on the beach.

In addition, he incorporates images of weapons left unused that are portrayed with the textures and colours of rust. For him, the ‘concept of corrosion is a metaphor for the present condition of the Acehnese,’ who he considers to be suffering from a state of ‘cultural decay’. Mahdi’s visualisations aim to expose the hidden pain in the hearts and minds of the people; a pain that is built on trauma.

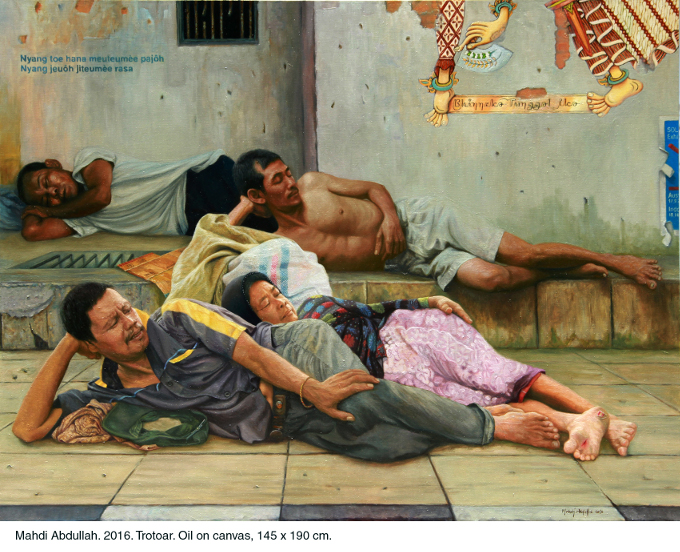

Other images painted by Mahdi are of homeless people sleeping on the streets and hawkers selling their wares. In Trotoar (Footpath), for example, he depicts a scene he witnessed one morning in the Old City of Jakarta. As he described, ‘I sketched a husband and wife sleeping on the footpath, then asked permission to photograph them. Their weariness came from the hardship of making a living. Their physically demanding lives had wounded their bodies, as symbolised by the sore I painted on the sole of the woman’s foot. The wayang character at the top right hand corner represents the Indonesian national motto in Sanskrit or Old Javanese language, Unity in Diversity.’ In Mahdi’s view, there are many Indonesian ethnic groups, especially outside of Java, that remain vulnerable to the devastation of conflict and the social issues associated with poverty.

|

|

Supplied by author. (Mahdi Abdullah) |

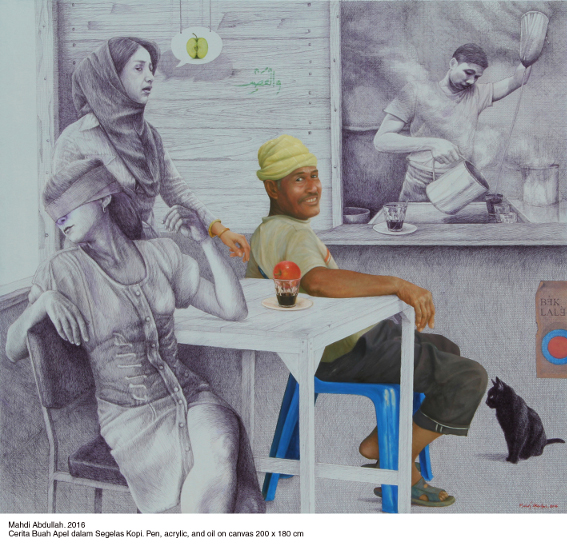

An especially interesting painting with a post-tsunami, feminist theme depicts social change resulting from the fact that after the tsunami women were allowed in Banda Aceh’s coffee shops. In Cerita Buah Apel dalam Segelas Kopi (Story of an Apple in a Cup of Coffee), Mahdi paints a scene showing an expatriate woman sitting in a Banda Aceh coffee shop and a jealous Acehnese woman with an anguished expression on her face looking at her seated husband, who is waiting for the proprietor to finish making him a cup of coffee in the traditional Acehnese way. Through selective colouring, Mahdi lures the viewer’s eye to what he calls the ‘centre of interest’, in this case the husband seated at the table, an apple (a symbol for Adam’s temptation and ‘original sin’) resting on his coffee cup, and the hand, wrist and bracelet of his wife standing behind.

In such works, Mahdi asks us to contemplate several issues. Firstly, jealousy, especially as a consequence of polygamy. Secondly, the painting suggests a criticism of those who are idle, drinking coffee and wasting time; ‘it’s not that the Acehnese people are lazy but that many of the unemployed just sit around.’ Finally, he invites the viewer to think about the changing norms of behaviour around coffee shops in Banda Aceh that are no longer exclusively for men. The sitting expatriate woman, who is blindfolded, ‘represents people who don’t want to know the culture and the changes it is undergoing.’

|

|

Supplied by author. (Mahdi Abdullah) |

Mahdi Abdullah is one of Indonesia’s most significant painters. His technically accomplished works are beautiful and meaningful, and may also be appreciated for their gentle and implicit depiction of individual human emotion seen in his subject’s faces and their body language. His artistic social commentary on the situation of women and men in Aceh, a province that was closed to the outside world for three decades due to war, is important for the world to see. Those who were lucky enough to view this remarkable exhibition have indeed been enriched by the experience.

Karen Kartomi Thomas (karen.thomas@monash.edu) is an ARC research fellow in the Indonesian Arts in the Sir Zelman School of Music at Monash University, Melbourne.

Related articles from the archive

|

Jun 07, 2009 |

|

|

Jul 31, 2010 |

|

|

May 27, 2012 |