A Hazara fleeing persecution has dedicated her life in Indonesia to helping her fellow refugees in Bogor

‘Here we are in transit. We can’t go back to our home country, we can’t go forward, we are totally stuck and we don’t know for how long. We are in limbo.’

These are the words of Kalsoom Jaffari, a Hazara from Pakistan, currently living as a refugee in West Java’s rainy city of Bogor. She landed on Indonesian soil in August 2013 and has been waiting to be resettled in a third country ever since.

‘I’m originally from Behsood, where there are a lot of problems with the Taliban,’ Kalsoom tells me when I visit her in her very simple rented apartment in Bogor where she lives with her brother, Sikander. ‘In Afghanistan we are severely persecuted.’

Before her estranged life in Indonesia, Kalsoom was working for the UNHCR in Pakistan as a health and education coordinator and with Mercy Corps Pakistan’s Integrated Health Program as a community health educator. Being a Hazara woman working for an NGO, and also a Shia Muslim, she found herself on an extremist target list, which meant her life was in grave danger.

Kalsoom opens up to me as we sip tea in her living room. ‘In March 2013, while working in the field providing an education at schools in refugee camps, a group of terrorists tried to kidnap me with my driver. We escaped but we received a phone call saying that this time we got lucky. I was supervising 16 of these camps at the time. I never thought that one day I would become a refugee.’

She continues, ‘The terrorists have no mercy for the young, the old, for women, for nobody. They will stop a bus and open fire on the Hazara because of this face.’ She points to her fair skin, which is what differentiates her from others in her home country.

Kalsoom’s father passed away when she was very young, and her mother and three younger sisters are still in Pakistan. Both of her sisters have stopped their studies because of threatening letters from terrorist groups. Kalsoom and her brother were forced to flee and seek asylum in another country.

|

|

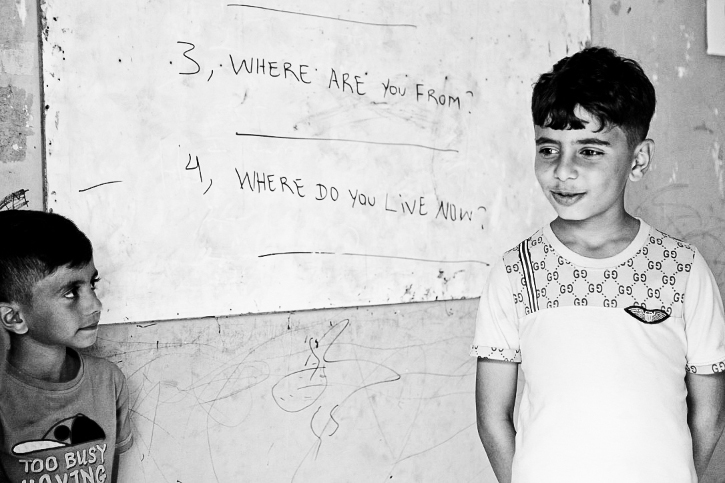

Refugee children in class at the Cipayung Refugee Educational Center. (Angela Richardson) |

Before arriving in Indonesia, Kalsoom and Sikander paid US$7000 (A$9260) each to an agent who organised their safe passage to Indonesia as asylum seekers. They travelled from Pakistan to Malaysia, continuing by boat with 13 other asylum seekers, eventually landing in Medan.

‘When we arrived on the shores of Sumatra, we had to walk through the jungle at night. It was so dark and the guide had to cut trees to make a path,’ Kalsoom remembers. ‘The next day we were in a car driving around Medan for the entire day to avoid the immigration police. The air-conditioning was on and we were shivering because our clothes were soaking wet.’

Before alighting at Medan Kualanamu International Airport, the driver told them to stay in the car as he went to get their tickets. Three men came and knocked on the car window. They claimed to be from Immigration and said they were going to arrest everyone unless they paid US$1000 each.

‘We were so scared. They showed us their IDs but since we didn’t know anything about Indonesia, we didn’t know if they were real or not. In the end they took US$500 per head.’ US$500 is exactly the amount Kalsoom’s agent told them each to carry on the journey.

‘We are separated from our family,’ she shares, with concern in her voice. Her youngest brother is currently in Melbourne, Australia on a bridging visa. He is also not allowed to work but he does what he can to help Kalsoom and her brother. ‘Hopefully one day we will be resettled in a third country, but we don’t know whether that would be Australia, Canada, New Zealand or America. If Australia, then at least we would be reunited with our brother.’

Kalsoom received her refugee status from the UNHCR in March 2014 but has heard no news since. She sends the UNHCR emails, letters, and has visited many times, but to no avail. ‘To visit, I have to leave at 4am and sit in front of the UNHCR gate in the morning until they open at 7am. Most of the time we don’t get an appointment. When I call them, the lines are always busy and I end up spending all my phone credit.’

According to Kalsoom, the UNHCR has just 49 staff for the entire asylum seeker and refugee population in Indonesia, of which there are over 14,000. Kalsoom says 6,000 live around Jakarta and Bogor, with the remainder in refugee centres across the country that she refers to as ‘prisons’. The UNHCR prioritises resettling families. As Kalsoom and her brother are both single, they have been waiting four years. ‘I’m even thinking to get married here!’ Kalsoom manages to joke.

According to Kalsoom, all of the refugees are struggling to survive. As they are not permitted to work during their stay in Indonesia, they rely on money sent from their families back home. Most of the asylum seekers and refugees eat once or twice a day to save money. They have developed unusual sleeping patterns in an attempt to conserve energy and funds, going to bed very late at night (around 2 to 3am), and waking up at around noon. When they awake, they eat breakfast, which will usually consist of a cup of tea and some bread.

‘Our rent here is expensive,’ Kalsoom shares. ‘We can’t boil the tap water to drink because it’s totally brown. This leads to a lot of health problems when the water is used for showering and even drinking, including stomach problems, scabies and also vaginitis.’ Kalsoom helps by conducting health workshops for refugees, providing them with a kit that includes basic health items and toiletries.

Kalsoom herself has recently been diagnosed with the autoimmune disease lupus due to environmental and lifestyle factors, namely stress and a poor diet. She suffers from painful and swollen joints and has not been able to start a course of medication due to lack of funding.

Although she is unwell, Kalsoom has been extremely proactive and has used her time in Indonesia to help other refugees and asylum seekers better their lives. When she first arrived in Bogor, she noticed some children playing outside. When asking the parents why they didn’t send their children to the only refugee school open at the time, they replied that they couldn’t afford the transportation costs.

|

|

Refugee children learning English at Kalsoom's school, the Cipayung Refugee Educational Center. (Angela Richardson) |

This inspired Kalsoom to do something. ‘I went to a stationary shop and bought some notebooks and pencils. I felt that if I didn’t do this, nobody would support them. It cost Rp.110,000 (A$11), which is a lot of money for me, but the peace I felt inside me was unique. I can’t explain it.’

With the books in hand, Kalsoom informed the parents in her neighbourhood that she would be teaching the children in the evenings. Starting by teaching English to three students in her home, the size of the class continued to grow to 40 students today, with classes taking place at a small rental-home-turned-school called the Cipayung Refugee Educational Center. Classes were even extended to the children’s mums, who today come twice a week to learn sewing and crocheting in Kalsoom’s living room.

The women, who now go by the name Refugee Women Support Group, are equipped with the skills to make pouches, pants, purses and even dresses. Handicrafts made are sold in different non-profit bazaars in Jakarta and via the online organisation Beyond the Fabric, run by a group of friends.

‘We do this to empower the women. In our culture back home, these women are not allowed to go outside alone or to earn an income; men have authority.’ The women, who are from Iraq, Ethiopia, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran, love coming to class and would never miss a session.

|

|

Kalsoom Jaffari showing some of the beautiful dresses made by the women from her Refugee Women Support Group (Angela Richardson) |

Most of the women who take Kalsoom’s classes had never touched a sewing machine prior to joining, and are now able to make beautiful creations. They are able to express themselves, keeping busy at the same time, while earning a little bit of pocket money.

Through personal donations from expat friends she’s made in Jakarta, Kalsoom has somehow managed to keep her school alive, as well as continue to pay rent and electricity in her humble home where the women meet.

Together with her friend Mohammad Baqir Bayani, Kalsoom has started the Health, Education and Learning Program (HELP) for Refugees project, with ambitious plans to open a refugee school in South Jakarta. The school plans to provide an education for children, teach computer literacy to young adults, as well as provide health workshops to adults. Activities like sewing and handicraft classes will also be offered to mothers.

Kalsoom has become a very respected figure in her community in Bogor. Although she comes across as extremely strong, it is clear her past and present hardships and future uncertainties are taking a toll on her. ‘I miss my home and my family, but I am not safe there. Here I’m safe but my loved ones are not with me,’ she tells me with sadness in her eyes. When asked what her fears are, she answers, ‘Even if I'm tired I cannot sleep. I fear too much about what's going to happen and I worry about the safety of my family back home.’

Angela Richardson (angelajelita@gmail.com) is a freelance journalist based in Singapore with a passion for human rights and environmental stories. Twitter: @angela_jelita

Related articles from the archive

|

What the future might hold |

|

|

Ugly sanctuary |

|

|

Staying stuck |