Natali Pearson

Mindful that the adrenaline coursing through your veins must not disturb the rhythm of your breathing, anxious about the command you have over your body, hyper-aware that every movement is being watched by an audience sitting beyond the spotlight: for dancers, such is the experience of being on stage – a state of focus and anxiety in which everything counts. Some would call it flow.

Internationally acclaimed dancer and choreographer Eko Supriyanto, who hails from Central Java, is accustomed to such experiences on stage. But it was not until he embarked on an extended artist’s residency in Jailolo, Halmahera (part of the province of North Maluku in Eastern Indonesia) that Supriyanto discovered another place where he could experience these feelings of being present, mindful and consequential: underwater.

In 2011, the regent of West Halmahera invited Supriyanto to choreograph a dance involving 350 youths. The dance, to be performed at the annual Jailolo Bay Festival in 2013, was a chance for this remote community to translate its unique culture and traditions into what Supriyanto calls ‘the vocabulary of dance’, and to bring this universal language to a wider audience. This challenge was even more remarkable because none of those performing had professional dance training.

Central to these dance vocabularies was the community’s deep connection to the ocean, something Supriyanto discovered after he went diving with some of the would-be dancers.

The experience was deeply transformative.

Here, under the waves, fish became his silent audience. An oxygen tank, rather than his dancer’s feet, became his most important tool. Regulating breath and heartbeat had never been more important, and he had no choice but to embrace the new challenges posed by the marine environment. As Supriyanto, who is now pursuing not only scuba but also free diving, explained it to me, being deep under water creates:

… a state of concentration, awareness and intention. Every detail of movement affects what you do. You cede control underwater and enter the state of dance – a state of anxiety, adrenalin and focus. A state in which you have no control.

Cry Jailolo, which developed out of Supriyanto’s earlier work in Jailolo, premiered in October 2014 at the Indonesia Dance Festival. Since then, it has toured internationally including, from 7 to 10 January 2017, at Carriageworks as part of the Sydney Festival. As Supriyanto explained in an interview with Julia Winterflood, through Cry Jailolo and its companion piece Balabala, he hopes to stimulate ‘a deep discussion on Indonesian contemporary dance and its relation to tradition’.

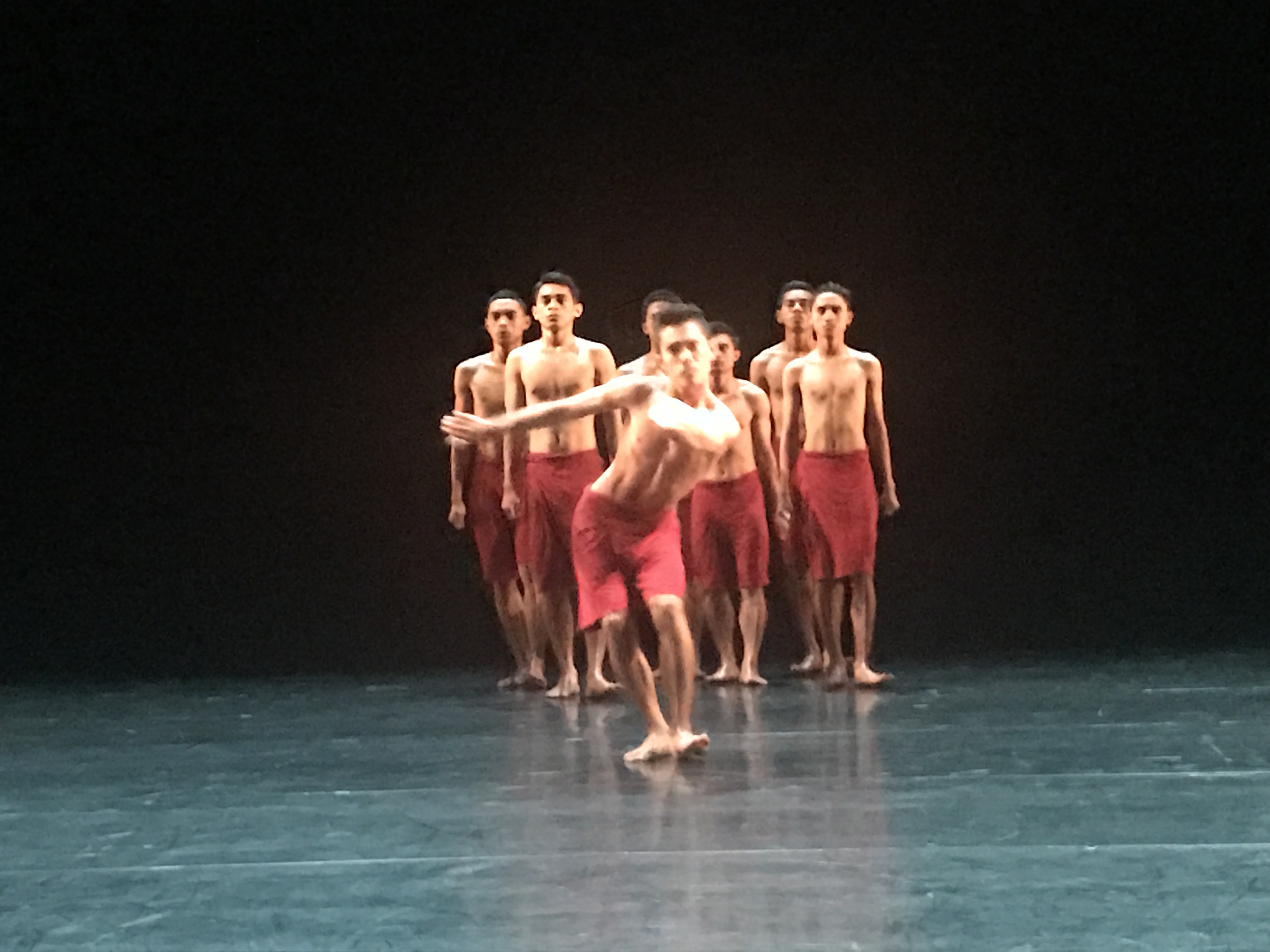

Cry Jailolo begins in darkness, with the sounds of a foot, then a heel, repeatedly hitting the floor. Gradually, dim light reveals a male dancer clad in red shorts. Painted on each thigh is a white stripe extending down to his middle toe. Later, the dancer’s whitened palms will flash in the darkness like bright fish in black water. As his foot and heel pound their unrelenting one-two beat, the dancer is joined by six other men – youths really, as the eldest is aged just 22 years. This powerful pulse barely ceases throughout the entire 60-minute performance, bringing to mind the rhythm of waves hitting the shoreline. It is an incredible feat of athleticism that invites respect for the dancers’ physicality and energy.

Cry Jailolo begins in darkness. (Credit: Natali Pearson)

The dancers explore the maritime world on stage – imagined paddles are deployed and schools of fish emerge. A whirlpool builds and then recedes like the tides. The overwhelming impression is of a community of people intensely connected with the water. Supriyanto has described Cry Jailolo as:

… my reflection on the destruction of the underwater world in West Halmahera, including dynamite fishing. It is also about the military history and social conflict between Muslims and Christians in the area. Perhaps it’s something of a social reconciliation that focuses on youth and the community.

Also showing at the Sydney Festival was the international premiere of Supriyanto’s Balabala. This work features five young women from Jailolo; again, the performers have only been dancing a short time.

At the show I attended on 8 January, a regular festival-goer sitting nearby suggested that performances the night before had been ‘fragile’. Perhaps this nervousness can be attributed to opening night nerves, or to the fact that these women had never danced (or travelled) outside of Indonesia. However, the performances I witnessed from these women, with their scraped-back hair and loose black clothing, were marked by confidence, determination and a fierceness that belied their age. I witnessed this same festival-goer later subconsciously shaking her fist in an embodied response that mirrored the dancers’ own fist-shaking.

This fist-shaking appeared as an expression of anguish, defiance or both, and reflected Supriyanto’s intention to explore, through dance, ‘what strength means for these young women’. He also draws on pencak silat (Indonesian martial arts) to make a powerful statement about the resilience required by these young women in the face of community expectations about their roles as wives, mothers and providers. The fist-shaking was the culmination of almost an hour of quietly powerful dancing, marked by solo interludes, joyous group dancing and noisy chitter-chatter in North Moluccan Malay. One of these young women, in particular, has mastered the art of dancing with her eyes, at one point turning her back to the audience and glancing knowingly over her shoulder towards us, her hidden audience.

A dancer throws an intense glance back at the viewer in this Balabala poster. (Credit: Natali Pearson)

Having finished their all-too-brief run in Sydney, these works will travel to Tokyo, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide, Europe and then to other international destinations including the Ramallah dance festival in Palestine and the National Theatre of Taiwan. Supriyanto is also working on the final piece of this maritime trilogy, Salt, inspired by his experiences swimming with baby barracuda near Jailolo. It will premiere later this year in Belgium.

Despite its spectacular diving sites, remote Jailolo remains best known as part of Indonesia’s famed North Maluku Spice Islands – the only place in the sixteenth and seventeenth century that produced cloves. European powers vied for access, influence and eventually control of these islands. The warring relations between nearby Ternate and Tidore further cemented their place in the historical record. Through Supriyanto’s work, these islands may now find themselves known for another reason.

Cry Jailolo and Balabala make connections between dance and the underwater world. By bringing attention to a part of Indonesia often overlooked in terms of modern infrastructure development, legal reform and business investment, these performances are also political statements about the sustainability of marine resources and the cultural inheritance passed down to Indonesia’s (non-Javanese) youth. In so doing, they speak to the problems of over-fishing and the health of our oceans, the legacy of culture and tradition, and, ultimately, how this vast archipelago – a sea sewn with islands – values its maritime domain.

Fragile indeed.

Natali Pearson (natali.pearson@sydney.edu.au) is completing a PhD at the University of Sydney on underwater cultural heritage in Indonesia. She is co-editor of ‘Perspectives on the Past’, a blog on history and heritage in Southeast Asia (www.SEAsiaPasts.com).