Michele Ford and Vivian Honan

Indonesian consumers have embraced app-based transport services with wild abandon. They’re quite likely now to hail motorcycle taxis, or even bajaj (three-wheel motorcycle taxis), with a few taps on an app. Chances are the app they are using belongs to Go-Jek, a popular local motorcycle taxi company.

These app-based transport services are not only more reliable – but also cheaper – than their conventional equivalents. But what has been the impact of app-based services on motorcycle taxi drivers? Have they improved their working lives, or simply increased levels of exploitation?

The rise of Go-Jek

Go-Jek’s name is a play on the Indonesian word for motorcycle taxi, which is ojek. The company was established in 2010 by Nadiem Makarim, who had studied at Harvard and was then working for McKinsey in Jakarta. Like many others, Nadiem found himself resorting to motorcycle taxis to cut through the traffic on the way to and from work, and began wondering if there wasn’t a better way to do it.

Having spoken to many motorcycle taxi drivers, Nadiem pieced together a picture of their working lives. It struck him that the majority spent most of their time waiting for fares. His solution: if drivers and clients could be connected, customers would have a better experience and the time of drivers would be better utilised, leading to an increase in their income.

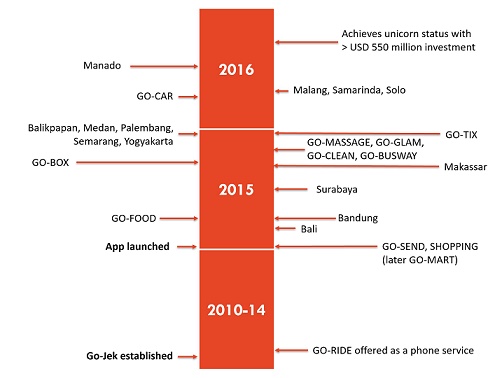

Go-Jek’s rapid rise began with the introduction of its app

Go-Jek started as a phone-based service in 2011. But it wasn’t until the company launched its app four years later that Go-Jek truly took off. Since then, Go-Jek’s footprint has expanded rapidly. Its heartland remains Greater Jakarta, but its signature green helmets and jackets can now be seen on the streets of Bali, Balikpapan, Bandung, Makassar, Malang, Manado, Medan, Palembang, Semarang, Samarinda, Solo, Surabaya and Yogyakarta.

Go-Jek has become more than a means of transport – it is a phenomenon. School students, office workers, bureaucrats – everyone is talking about Go-Jek. President Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo is certainly a fan, having regularly sung Go-Jek’s praises, even inviting Nadiem to the United States to help sell Indonesia’s digital potential. This confidence appears to have been justified: in 2016, Go-Jek became Indonesia’s first ‘unicorn’, raising US$550 million in new capital.

Go-Jek’s new empire

Having successfully made the transition to the online environment, it occurred to the company’s founders that drivers could also run errands, for example picking up phone chargers or buying cigarettes.

By 2016, the company had developed 12 separate services, all offered through the app. Go-Ride is the new name for Go-Jek’s motorcycle taxi service, which is now complemented by two other transport services in Go-Busway’s live-time schedules for Jakarta’s busway system and a service called Go-Car. Go-Send and Go-Box offer courier and removal services, while the popular Go-Food and Go-Mart apps have been joined by Go-Clean, Go-Massage and Go-Glam. Go-Jek has even ventured into entertainment services with the introduction of Go-Tix. Not all of these services are offered in all cities where Go-Jek has a presence, but it’s is definitely no longer just a Jakarta thing.

The final element in the system is Go-Pay, a virtual wallet that allows users to pay for the services Go-Jek provides by topping up their balance using an ATM, or through mobile or internet banking. This is a vital element of the Go-Jek ecosystem, which gets around the payment system problems faced by online businesses in Indonesia, most of which still rely on cash payments or transfers made physically at a bank.

Go-Jek’s services now include everything from massages to home removals

Pushing back

Consumers may love Go-Jek and other app-based transport companies, but many others don’t. They have been targeted by vested interests in the transport industry, whose calls for greater regulation have been supported by the transport authorities. Conventional taxi and motorcycle taxi drivers are also frustrated. The online transport companies are undercutting them and over-saturating the market, and so threatening their already vulnerable livelihoods.

Tensions were clear on 1 September 2015, when thousands of workers rallied outside the Palace in Jakarta protesting against job losses and demanding better health insurance – prompting Jokowi to attempt to mediate between Go-Jek drivers and conventional motorcycle taxi drivers. In another example a few months later, a brawl broke out between Go-Jek drivers and conventional motorcycle taxi drivers on the campus of the University of Indonesia. These were certainly not isolated cases. Such was the severity and frequency of conflict at FX Sudirman that Go-Jek set up a shelter at the shopping centre for their drivers to protect them from intimidation.

There has also been conflict in other cities. Several Go-Jek drivers in Makassar admitted they choose not to wear their uniforms out of fear of being targeted by conventional motorcycle taxi drivers. In Yogyakarta, Go-Jek drivers avoid areas where conventional motorcycle taxi drivers wait for passengers for fear that a fight could break out. Drivers interviewed in Bali also recounted their experiences of intimidation and threats from drivers in the conventional transport sector. Similar instances have been reported in Bandung, Medan and Surabaya.

Conflict reached new heights in Jakarta during the Blue Bird strike of March 2016. As they passed by Sudirman station, a convoy of drivers employed by the taxi company was attacked by Go-Jek motorcycle taxi drivers who threw rocks and sticks. In another location, a brawl broke out between the protesters and passing Go-Jek drivers, who had to be rescued by police. Shortly after, several waves of Go-Jek drivers approached taxi drivers demonstrating in front of the national parliament building, only to be stopped by police before physical contact could occur.

Flocking to Go-Jek

Despite the evident downsides of wearing the green helmet, hundreds of thousands of conventional motorcycle taxi drivers have made the switch to Go-Jek, hoping to improve their economic prospects.

Go-Jek hires motorcycle taxi drivers up to 50 years of age. They must have their own motorcycle, but are issued with two helmets and a jacket, and given basic training and an android phone to be paid off in installments. They are also covered by the company’s medical and accident insurance.

Since the company’s model is based on price competitiveness, Go-Jek drivers earn far less per trip than regular motorcycle taxi drivers. But they have the potential to earn more overall, because they are likely to accept more fares per day than regular drivers and receive bonuses for completing a certain number of trips.

In the early days, Go-Jek drivers were raking it in. One Jakarta-based driver told us he had made seven million rupiah in a month upon first signing up with Go-Jek in October 2015. Over time, however, the ability to accrue a large number of trips has declined as more drivers are recruited. The company has also dropped drivers’ share of the tariff by 25 per cent and increased the number of points required to access bonuses.

The honeymoon ends

Even with these changes, Go-Jek drivers continued to earn more than their peers. In January this year, regular motorcycle taxi drivers reported earning between Rp.50,000 and Rp.100,000 per day, while Go-Jek drivers reported making a minimum of Rp.150,000. Although Go-Jek drivers are still relatively well-off, there is widespread dissatisfaction with the company’s high-handed approach.

In November 2015, hundreds of Go-Jek drivers staged a demonstration outside the Go-Jek office, protesting the reduction in driver income. Some described the event as a strike. Further protests broke out in the following month in Jakarta, Bandung, Denpasar and Makassar, when Go-Jek suspended drivers accused of creating ‘fictive orders’ – a practice where drivers maximise their access to subsidies and bonuses by sending themselves orders on a second phone.

The largest of these demonstrations took place in Denpasar, where 1400 drivers were suspended without notice. In some cases, their motorcycles were confiscated for not paying company fines. Seventy of the suspended drivers approached the Bali Legal Aid Institute (LBH Bali), which organised a meeting for them with Go-Jek management and representatives from the ministries of transport and manpower, but no agreement was reached.

In Sulawesi, members of Makassar Go-Jek Drivers’ Union (Serikat Driver Go-Jek Makassar) threatened to shut down the Go-Jek office and resign en masse when management offered suspended drivers a choice between resigning or paying a fine. The demonstration continued for a second day in front of the Makassar City Government office, where the drivers demanded officials meet with Go-Jek management and fix the problem.

A shared target

So what does the Go-Jek experiment tell us about the impact of app-based technologies on this group of workers? Do Go-Jek’s moves to clamp down on drivers mean that it’s all bad news?

Internationally, the debate on app-based transport services has focused on the erosion of ‘traditional’ labour markets, as workers formerly employed in the formal sector are forced into informal sector jobs. But the vast majority of the Go-Jek drivers we interviewed earlier this year had previously worked as conventional motorcycle taxi drivers or in other informal sector jobs. And, unlike conventional taxi-cab drivers, conventional motorcycle taxi drivers are fully self-employed.

As Go-Jek ‘partners’, drivers continue to lack the job security or employment standards of workers in most formal sector occupations. But while drivers are contractors rather than employees, Go-Jek is an employer-like organisation in the sense that it not only set fees and regulates driver behaviour, but has the power to discipline drivers by depriving them of access to customers and therefore to income.

As a consequence, Go-Jek drivers have an identifiable target for collective action. Although their protests and mass actions have thus far been unsuccessful, their ability to collectively withhold their labour in a way that could damage the operations of the Go-Jek behemoth means that there is ultimately a potential for collective bargaining on wages and working conditions simply not available to conventional motorcycle taxi drivers.

Michele Ford (michele.ford@sydney.edu.au) directs the Sydney Southeast Asia Centre at the University of Sydney. Her research focuses on Southeast Asian labour movements. Vivian Honan (vhon6830@uni.sydney.edu.au) is a research assistant at the Sydney Southeast Asia Centre. She is currently also completing her honours year.