Yogyakarta’s little internet community, Taman Sari

Michael Romanos

In December 2011, the head of Yogyakarta’s Office of Information Technology and Telematics received an award from Indonesia’s Minister of Communications and Information Technology in recognition of Yogyakarta’s 'Kampoeng Cyber' village. The award made the residents of Kampoeng Cyber (previously known as Kampoeng Taman) and officials happy, but the city government had done nothing to deserve this award. Kampoeng Taman’s technology and internet use were not a city project. They were, and still are, a grassroots initiative of a few dedicated young artists, implemented with the active participation of the village residents. Their story is one worth recounting.

The story of Kampoeng Taman

Kampoeng Taman was settled in 1867 on the grounds of the ruined Taman Sari Water Castle by families made homeless by an earthquake, who over time established a thriving economy based on the production of batik cloth. The community showed its resilience when demand for handmade batik began to wane after the 1960s, as inexpensive commercial substitutes cut into its market. Capitalising on the emerging tourism market in Indonesia, the Kampoeng Taman artisans experimented with batik art, and soon they had developed a new cultural tradition, with art pieces in demand from both domestic and international buyers. This success brought new job opportunities and new customers. By 1978 there were more than 50 home studios and over 150 batik art galleries in Kampoeng Taman, and upwards of 100 men and women were occupied full time in production. In the 1990s, batik art was the mainstay of the local economy, and the village had gained an international reputation for its art and artists.

Child playing in the village - Credit: Michael Romanos

The Asian financial crisis of 1997, regime change in 1998, and the Bali bombings in 2002 had a major impact on Indonesian tourism, and within a short time Kampoeng Taman had lost most of its batik art market. Related businesses closed down, and unemployment increased so much that many residents had to leave the community in search of work. The community’s deterioration was rapid. The close links of a community industry in which most households were interconnected collapsed, and with it much of the social capital that had been built over many years of cooperation and partnerships. The social fabric of the community was torn, and so was its physical superstructure. Within a couple of years, Kampoeng Taman had become a slum.

A plan to revitalise the neighbourhood

In 2003, a group of young artists led by Samuel Indratma, Eddy Sulistyo, Koko Mariko, Asni Setyawah and Nasirun decided to address the economic and social decline of their community by mobilising its residents, capitalising on the community’s art batik tradition, and introducing computer technology and the internet for marketing and social connectivity. With the support of village rukun tetangga (neighbourhood groups)and village elders, these artists launched a community campaign to explain to the residents their ideas for the revitalisation of the community, and succeeded in gaining their support and active participation to carry out the development program.

Batik making at Taman Sari - Credit: Michael Romanos

Together, artists and residents launched a city-wide campaign to solicit contributions from individuals and business, and used the collected funds to purchase 25 computers, which they installed in strategically located households throughout the village.

They also approached Gadjah Mada University, the most prestigious academic institution in Yogya, and solicited its support. Gadjah Mada students were allowed to do their community service in Kampoeng Taman as part of their university education. Soon students were at work in Kampoeng Taman setting up a local area network, a central server, and an assistance office inside the village. They also started a training program in the use of computers for members of each household, designed a blog to showcase the village and to market its batik and other arts and crafts products. Meanwhile, the young artists mobilised the community to beautify the neighbourhood, improve the appearance of its streets, plant flowers, and paint wall murals.

Community cyber-revitalisation

Five years later, the community was thriving again. Unemployment had declined, its batik workshops filled orders coming from around Indonesia and many other countries, and village artists who had given up batik work returned to it. On a visit to one of the households, we talked to an 80-year old woman who was using the computer in her home. She told us that all nine members of the family used it for batik orders and sales, to read the news, to find cooking recipes, to communicate with friends and relatives, to do home work …. and declared that each member used the computer for at least three hours a day! When we told her that three times nine makes 27 hours, she gave us a big toothless smile and said: 'So, maybe we need another computer!'.

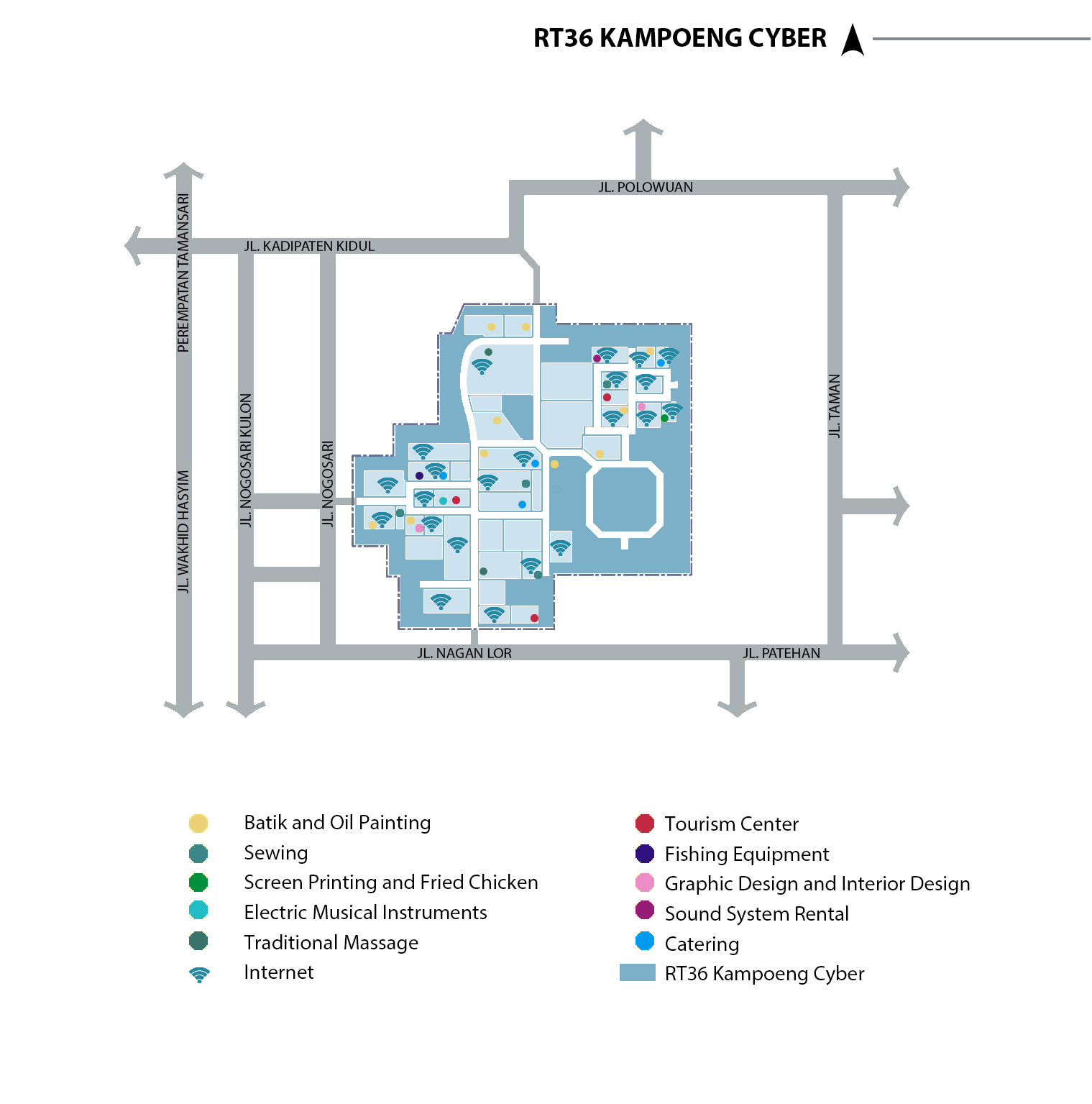

Map of Taman Sari - Credit: Michael Romanos

On the edge of the village that now proudly calls itself 'Kampoeng Cyber' stands the beautiful little Water Castle Cafe. Filled with old photos and batik art, it is a friendly setting now frequented by many of Yogya’s artists, intellectuals and students, as well as tourists. The cafe, which for years served as the village community centre, has now been transformed into a cultural gathering place for Yogya. From its veranda you can see the narrow flower path leading to the village, and the small homes beyond. It is a symbol of the transformation of this community, and a reminder that there is still a lot of work ahead. Hundreds of households in the surrounding area can be connected to the network, be given a computer, and be trained on how to use it.

Many more households in the villages of Yogya can adopt Kampoeng Taman’s successful model of community development. If the city administration wants to recognise the residents of this village, their grassroots initiative, and their technology innovations, it should duplicate their model and make such technology available to more of Yogya's poor neighbourhoods.

Michael Romanos (michalisromanos@gmail.com) is an Emeritus Professor in the School of Planning, University of Cincinnati, USA. He was trained as an architect, regional planner and economist, and has taught and conducted research in the Americas, Europe and Southeast Asia. In recent years, he has been involved in research on the role of the arts and cultural heritage in advancing community development, and has done fieldwork on this subject in Yogya and Bali.