Eliza Vitri Handayani

October 2015 was a busy and controversial month for Indonesian literature dealing with the history of the 1965–66 mass killings in Indonesia. First, there was the Frankfurt Book Fair where Indonesia was the focus country then, two weeks after that, the Ubud Writers and Readers Festival (UWRF) was held in Bali. In Frankfurt, the Indonesian delegation, sponsored by the Ministry of Education and Culture, held discussions with writers who have written about the mass killings; in Ubud, UWRF planned to feature events on the same topic but cancelled them after receiving warnings from the local police.

Police interference with UWRF’s program was the latest sign of paranoia about 1965-related events. In February, civilian groups working with the police disbanded a discussion with the victims of 1965 violence in Bukittinggi. In March, before a screening of Joshua Oppenheimer’s film, The Look of Silence, a crowd attacked the Sunan Kalijaga State Islamic University in Yogyakarta. Students and the police protected the campus, and the film was screened as planned. Two weeks before UWRF, under pressure from Salatiga police, the Satya Wacana Christian University banned and burned its student publication, Lentera, after its latest issue highlighted human rights violations in 1965. How to address, recognise and reconcile the trauma of 1965 remains extremely polarising in Indonesia.

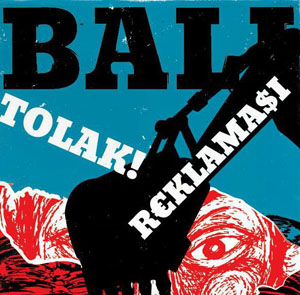

Two sessions unrelated to 1965 were also cancelled at UWRF: a panel called ‘For Bali’ about large-scale water and mangrove reclamation plans, big businesses, and the environmental movement, Bali Tolak Reklamasi (Bali Says No to Reclamation); and the launch of my novel From Now On Everything Will Be Different. The novel tells the story of two young people coming of age in the beginning of reformasi in 1998 and searching for the freedom to be who they are.

When the organisers informed me of the cancellation, I thought there had been a mistake or the police warnings had been extended to issues related to the 1998 student protests, anti-Chinese riots and rapes, which I talked about in my novel. I asked for an explanation from the festival organisers, who told me they had unsuccessfully argued that my novel was a work of fiction and should remain in the program.

The chief of Gianyar police revealed to CNN Indonesia that it wasn’t only issues related to 1965 that they had ‘advised’ be dropped from the festival’s program but also ‘sensitive issues … such as those related to race, religion, ethnicity, and other identity groups’. Since the New Order, Indonesians are constantly cautioned against bringing up issues that might foment sentiments about ethnicity, religion, and race, making people afraid to mention those things. Diversity has been celebrated superficially, through traditional dances and costumes, whereas discussions about the reality of relationships between various ethnicities, religions, races, and other identity groups have been discouraged.

Throughout the festival, speakers whose events had been cancelled responded in various ways – Bali Tolak Reklamasi held their event in Sanur instead of Ubud while Saskia Wieringa launched her novel, Crocodile Hole, independently at an Ubud cafe. While police officers and intelligence agents stalked the café, Wieringa’s publisher, YJP (Women’s Journal Foundation), supported by prominent lawyers, Nursyahbani Katjasungkana and Todung Mulya Lubis, encouraged the officers to have discussions with the author and an intelligence agent ended up buying Wieringa’s book. Still, the police continued to monitor the cafe and asked the cafe’s owner for her identity card.

YJP is experienced in dealing with the police and was in a position to offer high-profile connections as a means of protection for the cafe owner. I knew that if I arranged a similar ‘off program’ event, I would not be able to offer the same protection to my guests so I protested in my own way. Before coming to Ubud I had commissioned five t-shirts, each printed with a different politically critical excerpt from my novel, and I wore one every day to the festival. My t-shirt protest was within my means and spread information about my novel and the issues it raises whilst being a creative way to get around the censorship. On a few occasions police officers outside festival venues stared at me but mostly they ignored me. I sold all the copies of my book that I had brought with me to Ubud and I was interviewed by and mentioned in the media. Perhaps the most meaningful comments came from friends in Vietnam who told me that my protest had sparked new conversations in their circle about ways to deal with censorship.

Many activists and writers have criticised UWRF’s decision to comply with police pressures. John Roosa, author of Pretext for Mass Murder, and Human Rights Watch researcher, Andreas Harsono, made a valid point that in the reformasi era one could ask for documentation from the police listing their reasons and then challenge those reasons through legal channels. While UWRF complied, thus securing their permit and promoting the festival into the future, as I see it, they also protested and resisted. They wrote letters to the media and spread word about the police pressures to writers and journalists who, in turn, drew international attention to the issues of censorship, 1965, and freedom of expression in Indonesia. The festival also convened a panel called ‘Uncensored’ which discussed ways to respond to censorship.

As a point of comparison, in 2012 the hard-line FPI (Islamic Defenders Front) and the MUI (Indonesian Ulema Council) together demanded that a large publisher burn all copies of a book containing inflammatory comments about the Prophet Muhammad. The FPI threatened to wreck the publisher’s bookshops and take them to court for violating the Defamation of Religions Law, often invoked to limit unorthodox interpretations and expressions of faith. The publisher gave in to the FPI’s demands and invited MUI members to witness the book burning. If the publisher had resisted the demands to burn the book and instead pulled the book out of circulation and pulped it, they could have demonstrated their regret for publishing the book while showing they were not intimidated by the FPI. In contrast, UWRF’s response suggests that it is possible for businesses to resist a little, highlight the threats they receive and put pressures back on the government to protect citizens’ constitutional rights to freedom of speech.

.@elizavitri’s “From Now On Everything will be Diffferent” cancelled at #UWRF15 - she’s wearing it on her t-shirt ❤️ pic.twitter.com/iAq8lyejHQ

— Sunili (@sunili) October 31, 2015

Defamation, censorship and press freedoms

Threats against writers, journalists, and literary events come not only from the authorities or extremist groups, but also from powerful individuals and corporations. Defamation is covered by more than forty provisions in the Indonesian criminal code and charges are often used to silence criticism and accusations. Under the 2008 Electronic Information and Transaction Law, one can be arrested and jailed for suggesting online, even in private chats, that someone was corrupt or involved in a crime. Given the high level of corruption in the court system, corporate or individual business interests have great influence on the outcome of defamation cases.

Cases of violence against journalists are also alarming. The AJI (Alliance of Independent Journalists) Indonesia reported forty incidents against the press in 2014, the same number as 2013. In one case, Chelluz Pahun, an activist and journalist from East Nusa Tenggara, wrote about a district head using state facilities for party purposes. The district head subsequently sued him for defamation. Pahun’s house was vandalised and he was hit by a car. The police swiftly investigated him for defamation, but neglected to investigate the violence against him.

Furthermore, the ownership structure of the media, especially in the districts, may also work against critical journalism, as the owners of newspapers often have political or business interests. To push his editors to print his controversial stories, Pahun said he wrote about the same topic from various angles, so that his editors had no choice but to publish them. Journalists who are unable to write about a certain topic because they work for a bureau with vested interests in that topic have been known to share their notes and tapes with other journalists who work for bureaus that do not have the same conflict of interest. Journalists regularly use their networks and writing tactics to circumvent censorship.

In addition to political, religious and business interests, another excuse often used to curb creative freedom in Indonesia is ‘morality’ (read sexuality). In 2008 the Anti-pornography Law was passed, criminalising erotic content in the visual, literary, and performing arts. This law, along with fear of upsetting fundamentalist Islamic groups, made some writers and publishers practice self-censorship. Still, others defy this law and work in spite of existing legal limitations. Certain vocal organisations, such as the FPI, deem the topic of sexuality, in particular homosexuality, to be corrupting the morality of the nation and stage protests at literary events against writers and publishers that bring up sexuality. It is common for police to refuse to guarantee security and safety at these events and, instead, to blame the writers or organisers for inciting the crowd’s anger.

In 2012, when Canadian writer, Irshad Manji, launched the Indonesian translation of her book about being a Muslim homosexual, the FPI brought a large crowd to protest in front of the venue and threatened to cause mayhem unless the event was shut down. The Pasar Minggu district police chief disbanded the event citing lack of a permit, even though the discussion hardly qualified as a ‘large crowd gathering’ which requires a permit from the police.

In September 2015, politicians called on the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology to block a web series exploring the daily challenges of a gay couple in Jakarta. The call resulted in the producers taking down the series due to personal safety concerns, especially in light of MUI’s fatwa against homosexuals, which includes the death penalty. The state continues to fail to prosecute such hate-speech, whereas healthy self-expression keeps meeting with intimidation.

Standing up for change

Unless the state consistently prosecutes those engaging in illegal acts of intimidation – and successive reformasi governments have shown a reluctance to do so – similar setbacks will continue to appear. Setbacks not only to freedom of expression, but also to our efforts to be a dignified nation that is able to tell truthful stories about who we are, face up to human rights violations and calamities in its past and build a stronger future.

Writers, publishers and literary festivals play a significant role in stimulating political change. In the examples mentioned here, there were compromises but in various ways there is also resistance. In order to protect our space for artistic and journalistic freedom writers have started and signed petitions, activists are training journalists to be less biased in covering LGBT news, readers are disseminating banned journals online and private screenings and discussions on 1965 are being held in many places. These individuals and organisations are keeping the spirit and purpose of reformasi alive according to the risks each is able to take. By doing so they inspire courage in others and show the authorities that censorship, in fact, brings more attention to the censored issues.

Eliza Vitri Handayani (@elizavitri, elizavitri.net/sapa-contact) has published works in Griffith Review 49: New Asia Now, Asia Literary Review, Exchanges, Magdalene, and other publications. Her novel, From Now On Everything Will Be Different, came out in September 2015 from Vagabond Press.

Inside Indonesia 123: Jan-Mar 2016

{jcomments on}