Young researchers discover that the victims of history hold a secret every Indonesian should know

Ayu Ratih

In all the years I spent as a student under Suharto, the humanitarian tragedy of 1965 never came across to me as a complete story. As a little girl I often heard adults around me talking in frightened fragments about ‘those times’. They spoke in whispers. Occasionaly I would hear the word ‘Gerwani’ or ‘PKI’ when someone swore at some irritating person. But I had no idea what those words meant. (PKI stands for Partai Komunis Indonesia, the Indonesian Comminist Party, while Gerwani is an abbrevitaion of Gerakan Wanita Indonesia, the Indonesian Women’s Movement that was affiliated with the PKI). Even the film Pengkhianatan G30S/PKI (Treachery of G30S/PKI), which I watched almost every 30 September with my school, didn’t make much sense as a story. I do recall Ade Irma Suryani, the daughter of General Nasution, getting shot. And the screams of General Panjaitan’s daughter as she wipes her father’s blood off her face after he was shot by soldiers in front of their house. I was always afraid of soldiers. Maybe because the woman who helped my parents at home always frightened us if we didn’t obey her by threatening, ‘Watch out, the men in green are coming! They will take you away’.

It was my junior high school history teacher who first awoke my interest in the past. Miss Tridoso was a fabulous storyteller. But I don’t recall anything she might have told us about Indonesian history, let alone the 1965 tragedy. I learnt about world history, the history of Europe. Beyond that, history meant nothing to me. It was rote learning, the flag ceremony, carnival on independence day, and war films about revolutionaries with sharpened bamboo spears fighting Dutch soldiers who always thundered ‘Kowe inlander … Godverdomme’(‘You darkie … God damn you’). I reckon most Indonesian kids who studied history under Suharto have the same memories. And then I read This Earth of Mankind, Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s great historical novel, in the mid-1980s. Only then did I begin to understand the colonial atmosphere out of which Indonesia was born. History suddenly became a rich harvest of stories and an unending quest for knowledge!

Even so, Suharto never made it easy for anyone to like history. If you were especially interested in those who lost everything as a consequence of the 1965 tragedy, it could be positively dangerous. Picking up a Pramoedya novel was, in the eyes of the state in those days, a big mistake. Three young men were arrested and jailed in Yogyakarta in 1989 just for quietly distributing copies of Pramoedya’s tetralogy and organising discussions of it. The mother of one of my friends would not lend me her copy of This Earth of Mankind until she had snipped off the top right corner of the opening page with her name on it. I couldn’t believe it. If she was so scared, why did she own a copy of this banned book? And where had she obtained it?

I began to study history at graduate school. My friends and I surreptitiously tried to ferret out the bits of history that school and the mass media never told. We leafed through old newspapers that we could still find in the National Library. We smuggled in banned books from overseas. We photocopied forbidden reading matter from friends with similar interests (no internet yet). We started to write about what we read and talked about. Even more important to us were our first meetings with former political prisoners like Pramoedya, if they were not too afraid to see us. We talked with these ageing people about history, politics, culture, and their own daily lives being treated as pariahs in a nation for whose freedom they had fought. Nobody called them ‘victims’ yet – Suharto’s government regarded them as criminals. We called these people, who had once been historic pioneers, orang lama, or orla (people from the past). Our conversations with these orla would prove highly influential when we later began to conduct research into the tragedy of 1965. They told us who were the really important people, which events we should pay attention to and which stories we needed to uncover further.

We realised from the very beginning how important the stories of the orla were. This wasn’t some sort of romanticism on our part about the glories of the past. By listening and exchanging views with these historical actors we began to understand not just how the Suharto government had tried to exterminate everyone they considered communist, but how it had destroyed most of the thinking and progressive ideals that had given birth to Indonesia and made it a great nation. Throughout all these furtive discussions we were rebuilding an inter-generational bridge of knowledge that had been shattered by repression.

We had to wait until Suharto was brought down in May 1998 before we could expand our work further. Then we began to reach out to more historical actors. We made new friends among a younger generation. And we set up an institute as a home for what we realised had become our real work.

The birth of ISSI

In the middle of 1998 we became acquainted with the young men and women in the Tim Relawan untuk Kemanusiaan (TRK, Volunteer Team for Humanity). They had joined together to investigate the anti-Chinese riots that had taken place in Jakarta on 13–14 May, and to assist the victims. They taught us the word ‘victim’ and how important it was to be on the victim’s side. We started routine discussions at the TRK secretariat, and told them what we had learned about the 1965 tragedy. We decided to start an Oral History Project (OHP) to interview victims of the 1965 tragedy, especially those who were not famous. We called them ‘rank and file people’.

About fifteen people joined that first OHP team. They participated in intensive training and discussion sessions to help them do the interviews. At the end of 1999 the first teams went out to various cities in Java, Bali, Lampung and Central Sulawesi. Some of them experienced moments of discomfort. On both sides of the interview table the question arose: how far can we trust these people? Victims who had never talked about their experience were afraid of the consequences of bravely speaking out. Interviewers who only knew their history from school textbooks wondered if the victims’ stories were true and valid as historical sources. But most of them soon built a rapport with the victims and came home with incredibly rich stories full of human nuance. Their previous experience of talking with victims of May 1998 made it easier for them to win the sympathy and confidence of victims of the 1965 tragedy. They soon stopped demanding the ‘objectivity’ that had been drummed into them within the Indonesian university teaching system.

At least two male interviewers met with female victims of rape or other sexual violence. Women who would normally keep their mouths shut in meetings dominated by older men suddenly asked to speak personally with an interviewer. As these women poured out their grief and bitterness about what they had experienced, the interviewers felt confused. Shouldn’t they be doing something other than listen? Shouldn’t oral historians also be ready to help a victim overcome their problems? Such questions haunted us continually at the beginning of our journey. Those interviewers who had had experience supporting victims in other human rights violation cases felt strongly that they should act as well as research. However, we eventually agreed we had to separate our research role from our role of victim supporter, and we could do that without sacrificing the needs of the victim. We usually referred victims to friends in other organisations that had more capacity for advocacy and support.

Our experience of listening to women’s stories made us aware that female victims often needed a special space to open up. In male-dominated spaces they did not get the opportunities they needed. Even when they did speak up, the men present often could not restrain themselves from commenting on or correcting them. So we decided to focus intensively on women’s stories, in separate rooms. Together with friends from the human rights organisation Elsam we formed the Lingkar Tutur Perempuan (Women’s Story-telling Circle) especially to facilitate women’s meetings and interviews. This led us to push successfully for the official Komisi Nasional Anti Kekerasan terhadap Perempuan (Komnas Perempuan, National Commission on Violence Against Women) to hold hearings with female victims of the government operation to eliminate alleged PKI members and other communists in 1965–66. The commission issued its report in 2007 and submitted it to President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.

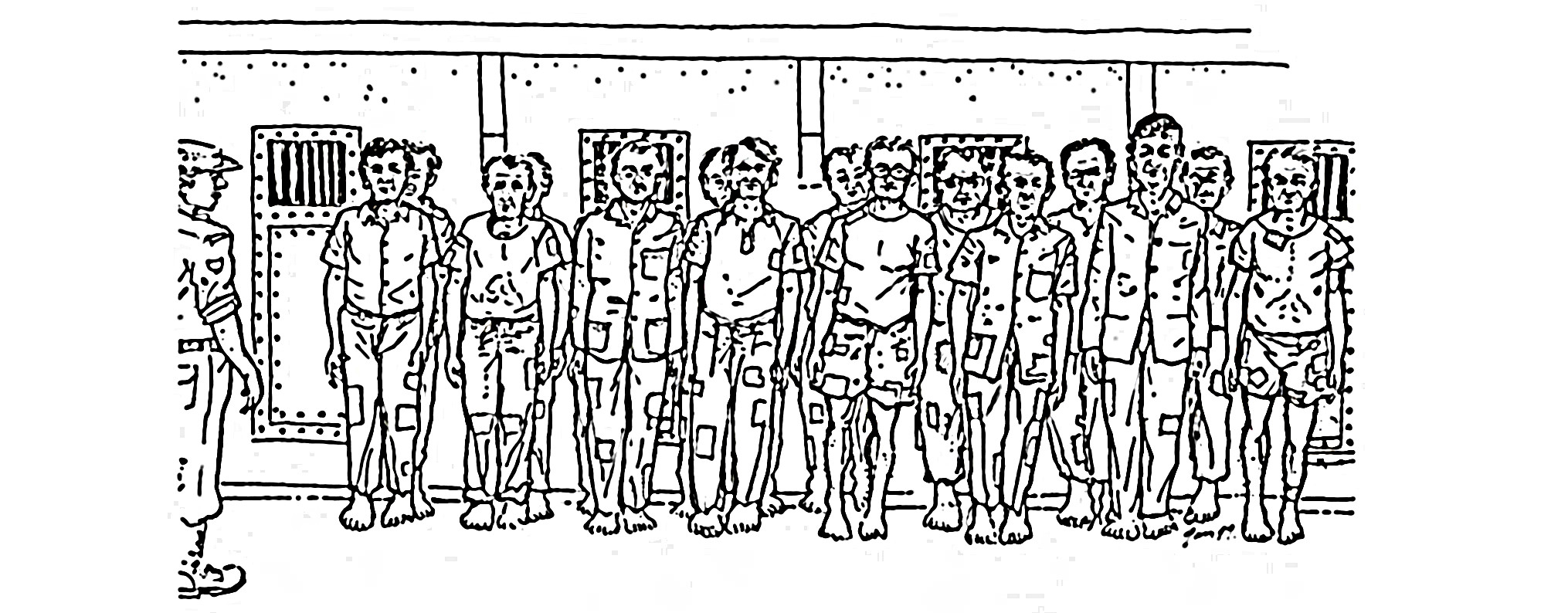

Our OHP also investigated violent incidents that occurred in specific locations. After at least 400 interviews we began to see that the methods that had been used to persecute alleged communists varied from area to area. Although on the whole the military, mainly the army, controlled the entire extermination operation, violent actions spearheaded by local military-supported forces claimed many victims. Paramilitary groups invaded homes, looted goods in houses, shops and offices, and killed those they regarded as enemies of the state and nation. Our local investigations revealed patterns in the persecution, and more broadly the special history, of an area. This helped strengthen the historical awareness of the researchers.

In 2003 we published a set of essays based on interviews we had conducted over the previous three years. At the same time we began to think of building an infrastructure to safely store all the interview recordings and documents we had collected. After consulting with friends who had supported us from the beginning, we decided to form the Institut Sejarah Sosial Indonesia (ISSI, Indonesian Institute of Social History), based in Jakarta. We agreed ISSI would not simply be a repository, but a research centre, a library, and an institutional archive that would look after our materials professionally and permanently.

This year ISSI enters its twelfth year, but our research into the 1965 tragedy has been going on for 16 years. We have interviewed about 500 people in towns in Sumatra, Java, Bali, Kalimantan and Sulawesi. All our interviews are recorded digitally. We have also made digital copies of many photos from personal collections, which we use to prepare high school teaching materials about the victims of the 1965 tragedy.

Listening and storytelling as political action

Through the OHP, our young researchers, who before this had never met a 1965 victim, have done far more than simply record their stories. They have resisted the demonisation the Suharto government carried out against those it persecuted. Several of them later said they discovered victims in their own wider families. Excluded people who had never said a word about their experiences sought out their young relatives who were asking questions about history. Gathering with other victims and telling their stories has helped many female victims to understand the extent of the oppression that has affected so many people. These older women also hope that by telling their stories it will help resolve the tension that arose when young people blamed their mothers for causing them so much shame and suffering.

Transmitting memories between groups and between generations like this is extremely important for Indonesian society as a whole. Society has been forced to forget the most profound parts of the nation’s history. For a very long time now, the nation’s memory of these things has been saturated with incomprehensible fears and vigilance, such as about ‘the latent danger of communism’ or ‘the emergence of a new PKI’. Every step to learn about history has been a hesitant one. Our views on history are frozen. What ISSI has done bit by bit the last 16 years is to melt the ice, especially about the tragedy of 1965. At the same time it has been building a new historical awareness that the people who were shoved aside to build the Indonesia we live in today have a secret we all need to know.

Ayu Ratih (gunggaratih@gmail.com) is director of the Indonesian Institute for Social History (Institut Sejarah Sosial Indonesia, ISSI). The institute’s website is at http://www.sejarahsosial.org/.