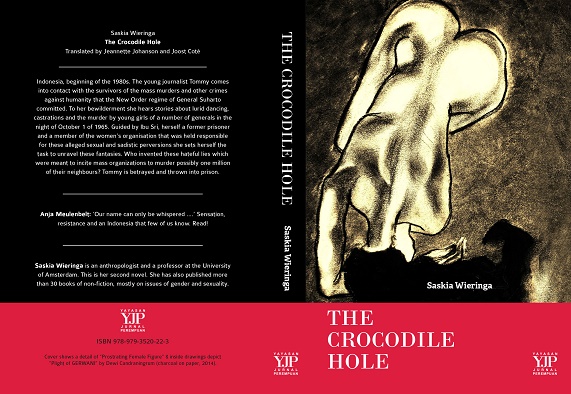

Joost Coté

It is often said that fact can be stronger than fiction. But the reported 'facts' concerning the events that took place around the Crocodile Hole on the air force training ground in Jakarta on the night of 30 September 1965 were in fact fiction; they were fantasies that inspired the terrible physical and existential experiences of millions of Indonesians in the months and years following that night. Like any good piece of fiction, the fantastic images created by words gained a corporeal reality through the illustrations, sculptures and cinematic representations that haunted schools, towns and printed media throughout the New Order era. As much as these events and the era they gave rise to can be and have been analysed and discussed in academic writing, the full horror of the resulting violence can only be imagined, and perhaps to a degree vicariously experienced, by approaching its reality through fiction.

This novel, in providing a fictionalised account of the lives of a group of real Indonesian women who experienced and survived unimaginable violence at the hands of a political regime, comes closer than many an academic account to putting the reader in touch with their experience. And not just that of the women victims themselves. The author’s deep understanding of the zeitgeist that was Java of the mid 1960s – and 1980s – based as it is on her own extensive research into these events and contact with these women, ensures that the reader also comes to gain an understanding of the society which at the time allowed this to happen.

The events described in this novel - murder, exile, torture, imprisonment, ostracisation, humiliation - take place in the Indonesian capital, Jakarta, almost 20 years after the moment which gave rise to them. Unlike many accounts of 30 September 1965 and its immediate aftermath, this novel deals with the continued suffering of the tapol, the political prisoners (those condemned but not murdered) who survived their many years of banishment. Too often forgotten – or indeed not known in the outside world – they and their immediate families remained under the surveillance of the regime after their release, remained isolated from everyday life. In this sympathetic portrayal of a group of elderly women, and of the stories of their past suffering, the reader can also feel the power of their redoubtable spirit. Only this enabled them to survive the years of incarceration, and then, afterwards, the humiliation of being rejected by their own grandchildren, the upright, well-schooled but unknowing citizens of the New Order.

Providing the crucial structural framework for the novel is the role of Tommy, the young Dutch would-be historian of the New Order. She is our guide through whom the events, the past and the 1980s present, are gradually revealed to the reader. She brings us into another world, into the secretive environment where these survivors are at least able to share their memories of pain, heroism and idealism that enable them to survive the ‘new order’. How, one may ask, does a foreigner gain access to this most intimate Indonesian experience? What right has a foreigner to do so? And, perhaps even: why should it be this representative of the former colonising nation, itself perpetrator of countless atrocities and often described as providing the model for the New Order regime, who represents the foreign interlocutor, who acts as the conduit for our understanding of these events?

For the reader from another time and another world Tommy is our avatar in this unreal world. The invention of Tommy as the narrator-investigator-protagonist character is presented not as a superior, analytical foreigner, but as one having to deal with her (and our) own oppressive ideologies and sexual fantasies. Not allowed to overwhelm the novel’s central concern, Tommy’s own struggle with her father’s Calvinist ideology, her own sexual fantasies and desires, her own uncertainties about her future which she reviews during her long nights in a Jakarta prison, and her own suffering at the hands of her gaolers, replicate in minor key the experiences of the women whose lives she is learning about. By engaging with this character, who operates, as it were, in the foreground, the reader is assisted to understand the myriad figures speaking in the background, whose real suffering, real experience, we – the readers from a different time, different generation and perhaps different country – can only hope to appreciate in abstract terms. Tommy’s own sexual fantasies similarly act, at one level, to palely echo those that lie at the heart of the Indonesian tragedy, and, at another level, provide her with an entry point into the modern world of 1980s Jakarta and her Indonesian experience. There, as another counterpoint to the events in Indonesia explored in the novel, we can also monitor the self-serving responses of the West – represented here, fittingly, by the officials of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands careful not to allow the events in Indonesia to tarnish their diplomatic image.

Were this fiction, one might expect the novel to provide the reader with a happy ending. But the story told in this novel is, of course, not fiction: the novel is a powerful representation of the reality that was Indonesia of the 1980s. In offering the reader a longitudinal view of the experience of life under the New Order regime, this novel will take an honorable place alongside more prosaic and academic accounts of the ideologically motivated persecution of millions of Indonesians between 1965 and 1998.

Joost Coté (joost.cote@monash.edu) is Senior Research Fellow (History) in the School of Philosophical, Historical & International Studies, Monash University. This article first appeared as 'Preface' to the novel The Crocodile Hole. It is reproduced here with the permission of the author.

The Crocodile Hole is available for free download via Academia.edu.

And you can watch Jurnal Perempuan's film on The Crocodile Hole here.