Meg Downes

In the early days of the reformasi period, Indonesia saw a boom in literature by young female authors, tackling topics that had been deemed taboo under the New Order regime. Labelled by supporters and critics alike as sastra wangi (literally ‘fragrant literature’), these narratives often contained highly explicit sex scenes and candid representations of female sexuality and desire. The ‘fragrant literature’ was widely hailed as a step towards women’s emancipation from stereotypical gender roles on the one hand, and accused of flooding the market with vulgar, sensationalist content on the other.

Over a decade on, some of these novels are achieving huge success on the big screen. The work of Dewi Lestari, for example, has resulted in five popular film adaptations released between 2012 and 2014. With more in production, it seems that ‘fragrant film’ is the flavour of the moment in Indonesia. Yet in contrast to the critical furore surrounding ‘fragrant literature’ in the early 2000s, there has been barely a ripple of debate about the film versions, or the continued activities of other young female authors in the literary scene.

This is partly due to dramatic changes in the way female authors are discussed in Indonesia over the past decade. The term sastra wangi has disappeared. It has been replaced by more varied ideas of female authorship. Previously prevailing notions of an elite male-dominated literary scene have lost much of their credence in a media landscape where not just female voices, but also Islamic voices (through popular Islamic fiction) and younger voices (through ‘teen’ literature) are increasingly narrating stories that matter to them.

Distinctions between popular writing and literary works are also becoming more fluid, as are the boundaries between writing, film, and everyday life. The most popular Indonesian films of recent years were adapted from novels, and young Indonesians frequently reference the stories as something larger than the bounded form of a book or movie. As popular media starts to infiltrate all aspects of daily life, the borders between media forms become blurred.

Fragrant films?

Widely adopted by the media (both in Indonesia and abroad) during the early 2000s, sastra wangi was quite a disparaging label. It implied a focus on the authors’ femininity rather than their literary work. The authors themselves, including Ayu Utami, Fira Basuki, Dewi Lestari, Djenar Maesa Ayu and Leila Chudori, objected to the categorisation as derogatory and disempowering.

Ayu Utami dismissed the phrase as ‘meaningless’ and ‘sexist’. Djenar Maesa Ayu argued ‘I’m not fragrant. Neither are my works.’ Dewi Lestari also refused to be lumped under the label, claiming the only similarity shared by the authors was that ‘we’re all young female writers producing work at the same time. But we choose different themes.’ Nevertheless, the label stuck. It became the central focus of much early reform era literary discussion. Today however, most young Indonesian readers have never even heard the term sastra wangi. They also do not appear particularly concerned with whether the authors they read are male or female.

Another telling development is the recent film adaptations of Dewi Lestari’s writings: Perahu Kertas (Paper Boat, 2012), Perahu Kertas 2 (2013), Rectroverso (2013), Madre (2013) and Supernova: Ksatria, Putri & Bintang Jatuh (Supernova: A Knight, a Princess and a Falling Star, 2014). In these stories, Dewi Lestari does not shy away from serious issues, or from desire and sexuality. Moreover, the Perahu Kertas films were directed by Hanung Bramantyo, who is well-known for courting controversy. However, in contrast to the reception of the early ‘sastra wangi’ novels, these films have provoked no public outcry. This is particularly interesting because – given its highly public and visual nature – film is usually the focus of more public debate and censorship impulses than written works.

The production and successful release of a major feature film in many ways legitimises the text it was drawn from, and in turn, the author who created the story. In this case, the widespread acceptance and popularity of these film adaptations shows that authors such as Dewi Lestari have shaken off the sastra wangi label and attendant controversy of the previous decade.

‘Teenlit’ and Islamic women’s writing

It is clear that a decade on from the initial hype over sastra wangi, there is nowhere near the same level of moral panic about young female authors narrating their own stories in a literary context. This is linked to multiple changes over the past decade. The most important of these are the emergence of ‘teenlit’ and Islamic women’s writing.

Teenage authors have burst onto Indonesia’s literary scene, with girls as young as fourteen publishing bestsellers. Some of the forerunners of this genre were Rachmania Arunita, Maria Ardelia, Dyan Nuranindya and Esti Kinasih, whose novels explore the highs and lows of everyday life for female adolescents in contemporary Indonesia. Rachmania Arunita’s Eifel I’m in Love (2003) was soon adapted into a film version, as was Maria Ardelia’s Me vs. High Heels (2004). The film adaptations have further reinforced the popular legitimacy of these young female authors.

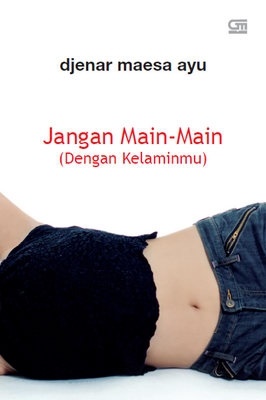

In the early days of the reformasi period, Indonesia saw a boom in literature by young female authors, tackling topics that had been deemed taboo under the New Order regime. The cover of Djenar Maesa Ayu’s Don’t Play (With Your Genitals).

In the early days of the reformasi period, Indonesia saw a boom in literature by young female authors, tackling topics that had been deemed taboo under the New Order regime. The cover of Djenar Maesa Ayu’s Don’t Play (With Your Genitals).

The rise of popular Islamic fiction, known variously as ‘novel dakwah’ (proselytising novels) or ‘sastra Islam’ (Islamic literature), has begun to generate another kind of literary identity. Long sidelined under the New Order regime, Islam is today a distinctive part of much Indonesian popular culture, including popular literature. Though not as wildly successful as some of their male counterparts (such as Habiburrahman El Shirazy), female Muslim writers like Helvy Tiana Rosa, Asma Nadia, and Abidah El Khalieqy have achieved notable distinction among readers.

This new space for female voices, Islamic voices and younger voices has disrupted conventional ideas about ‘literature’ and women’s place in it. The classic image of literature as an elite, secular, male-dominated scene has lost much of its power. It has been replaced by more varied ideas about authorship.

This diversity is a major factor in the decline of the sastra wangi label. It is no longer an exception for women to be narrating their own stories in Indonesia, or to be writing about topics other than being a good housewife. Rather, it is increasingly the norm. The shortlist for the prestigious Khatulistiwa prize for literature has been consistently dominated by female authors throughout the past decade. Female authors outnumber their male counterparts in many sections of bookstores.

Dangerous overlaps

Diminished anxiety and debate in contemporary Indonesia about female narration does not mean that books and films about gender and sexuality no longer cause controversy. Dewi Lestari’s name is widely greeted with smiles among young Indonesian readers, but some of her contemporaries remain more contentious. How is it that certain narratives are defined as fit for popular consumption, while others are seen as potentially dangerous?

Certain thematic combinations create particular anxiety; for instance, when explicitly Islamic narratives explore female sexuality and present Islamic feminist critiques of Islamic institutions. An example is Abidah El Khalieqy’s novel Perempuan Berkalung Sorban (Woman with a Turban), which was adapted and released as a film in 2009. The film’s director, Hanung Bramantyo, also directed the Dewi Lestari adaptation Paper Boat 1 & 2, but public reactions to the two films were very different. Unlike the widely acclaimed and long-running Paper Boat, Woman with a Turban faced public protests by radical group FPI (the Islamic Defenders’ Front) and was withdrawn from cinemas within a fortnight of its release. It was accused of presenting a negative picture of life in an Islamic boarding school.

The polarised reactions to these films demonstrates the continued divisiveness of debates around women and Islam in Indonesia. The rise of popular Islamic expression has certainly opened a space for female Muslim authors and contributed to broadening ideas of authorship. However, the belligerent reactions to certain stories point to an increase in the power of hard-line Islamic groups such as FPI to define appropriate female behaviour and expression, both in the media and in everyday life.

Increased variety, blurred boundaries

Indonesia's contemporary literary landscape is very different from a decade ago. The once powerful 'sastra wangi' label has receded with the emergence of more varied ideas about who has the authority to create ‘literature’. The New Order’s idealised vision of the good wife and mother has arguably been replaced by a diversity of contested female voices, reflecting current power struggles between conservative and progressive forces in political and social spaces. In this context, public debates around novels and film adaptations continue to play an important role in negotiating different notions of Indonesian identity.

Meg Downes (Meg.Downes@anu.edu.au) is a PhD candidate in the College of Asia & the Pacific at the Australian National University.