Pam Allen

It has been observed that while most Indonesians don’t care much for reading, a disproportionate number of Indonesians love to write. At a practical level, this creates problems in the publishing industry, with supply outstripping demand. While it is increasingly difficult to make a living out of being a writer, more and more Indonesians, and young Indonesians in particular, are attracted to creative writing.

This is nowhere more evident than in the number of submissions received by the Ubud Writers and Readers and Festival (UWRF). In 2014, there were 529 Indonesian submissions from writers in 125 cities in 27 provinces, of which only 15 could be selected. As in previous years, with financial support from the Hivos Culture Fund, those 15 selections were translated into English and published in a bilingual anthology launched at the festival.

Literary competitions – mainly for poetry and short story writing – are another sign of Indonesians’ interest in writing. These competitions attract thousands of entries annually, despite the less than glittering prizes. Particularly popular with secondary school students, one only has to look at sites such as www.anekalomba.com or www.ajangkompetisi.com, which are devoted to providing information on a vast array of competitions, from Koranic readings to t-shirt design.

Stories from the regions

Since the inauguration of the UWRF/Hivos collaboration in 2008, a feature of many of the UWRF stories has been their incorporation of local adat (custom), cultural practices, history and mythology. The 2014 anthology, for example, includes a story by an East Javanese writer about the tenth century King Airlangga; a story based on a Malay lullaby by a writer from Riau; a story about the arrival of a Chinese sailor in Sunda Kelapa, Jakarta in the fifteenth century and his subsequent conversion to Islam; and a story by a writer from Kalimantan about a Dayak shaman.

It might be argued that this phenomenon of ‘regionality’ is a cultural by-product of local autonomy, a kind of celebration of regionalism against the unitary state of Indonesia and the national culture. However, I’m not so sure if that is the case. The current crop of young writers drawing on these themes would have been barely in their teens when regional autonomy was introduced in 2001. Suharto’s authoritarian unity state was not part of their adolescent consciousness.

The post-Suharto political atmosphere has also led to another recent phenomenon: the imagining of the events of 1965. Such writing was formerly the domain of authors who had personally lived through these events: observers such as Umar Kayam and Ahmad Tohari in the Suharto era, and victims and survivors in the post–1998 period. In the last three or four years, however, fictional creations of these events have appeared, recollections of an imagined past. Examples of recently published novels include Cerita Cinta Enrico (Enrico’s Love Story) by Ayu Utami (2012), Amba (translated into English as A Question of Red) by Laksmi Pamuntjak (2012), Candik Ala 1965 (Trauma of 1965) by Tinuk Yampolsky (2011), Ayu Manda by I Made Darmawan (2010) and Pulang (translated into English under the title Home) by Leila Chudori (2012).

Muslim popular culture

While many elements of the Indonesian book industry struggle to survive, publishers of books on Islam continue to thrive. According to Afrizal Sinaro, chairman of IKAPI, the Indonesian Publishers’ Association, the success of Islamic books started during the economic crisis that led to the fall of the Suharto government in 1998. Sinaro argues that people ostensibly ‘found solace in religion’ at that time, and since then, Islamic book sales have been booming. Today, 40 per cent of the members of IKAPI publish exclusively Muslim books, which outsell schoolbooks.

The popularity of Muslim popular culture is evidenced by the annual Islamic Book Fair, organised by IKAPI in major Indonesian cities. With close to 400 booths at the 2015 Jakarta event, the fair attracts many more visitors than its secular counterpart. On sale at the fair is a vast array of Islamic-themed literature. There are romance books, cook books, joke books, children's books, books on sex, books on fasting, alms-giving, prayer and clothing, political books, and of course, the Koran, in Arabic or Indonesian. The bestselling books are practical ones on how to live life as a devout Muslim – apparently bought by recent converts or those ‘returning’ to the tenets of the Islamic faith.

It is worth noting that Muslim popular culture is not confined to the written word. You can hear Muslim ringtones on mobile phones everywhere. Television dramas often depict a worthy Islamic protagonist pitted against a depraved enemy, and Muslim preachers are regarded with cult status, while Islamic fashion shows are regular events.

Metropop

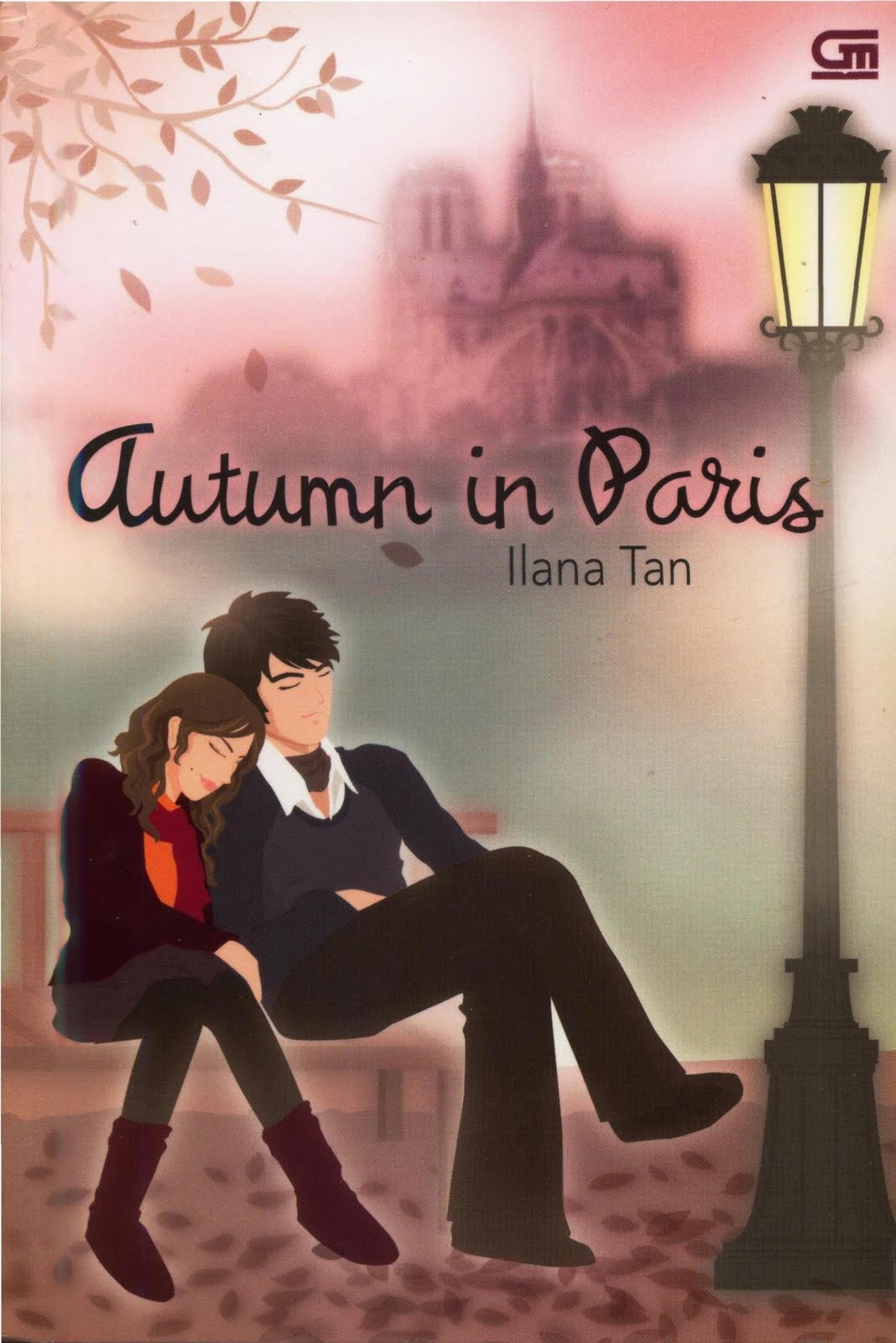

A hugely popular genre of writing in contemporary Indonesia is Metropop. An abbreviation of Metro Populer, Metropop is, as its name suggests, popular fiction with a metropolitan setting. These books usually have English titles. The plots are inevitably romantic, and are often set in cities outside Indonesia. This has been a successful formula for writers such as Ilana Tan (who may or may not be a real person, given the lack of images available of her). Her ‘Seasons’ series, comprised of Summer in Seoul, Autumn in Paris, Winter in Tokyo and Spring in London, is a good example.

Metropop books usually have titles in English and plots that are inevitably romantic, and are often set in cities outside Indonesia. Ilana Tan’s ‘Seasons’ series has set the pace in this genre.

Metropop books usually have titles in English and plots that are inevitably romantic, and are often set in cities outside Indonesia. Ilana Tan’s ‘Seasons’ series has set the pace in this genre.

Another is Winna Effendi’s Melbourne: Rewind (2013), which, with its metropolitan setting and a plot about the relationship between an Indonesian and a non-Indonesian protagonist, ticks the Metropop criteria of themes about love, loss and the past. While it is easy to be dismissive of such formulaic writing, these books achieve very high sales, and their popularity rates very highly on reading sites such as Goodreads. Ilana Tan’s Autumn in Paris (2007) is rated 4.05 stars (out of 5), based on 6452 ratings. Compare this to Ayu Utami’s 1998 novel Saman, widely heralded as the best literary work of the early reformasi years, is rated 3.54 stars based on 4468 ratings.

Virtual writing

Online publications continue to be a popular way for budding Indonesian writers to get their work published. These sites also provide forums for literary discussion and debate.

Cybersastra (http://cybersastra.org/) invites writers to submit manuscripts for online publication, and also maintains a directory of previously published work. However, there is noticeably less traffic on the literary discussions and forums on this site than there was two or three years ago. Social media plays a much wider role in disseminating views and information to a much wider audience than a site like Cybersastra. For young Indonesians interested in literature and writing, Facebook and Twitter are key platforms. It is well documented, for example, that Jakarta is the ‘Twitter capital’ of the world.

Warung Fiksi (http://warungfiksi.net/warung-fiksi/) promotes itself as a ‘professional organisation for creative writing’, publishing works and stories set in Indonesia: ‘a place where everybody can share the experience about Indonesian cultures, natures, and creatures’. Closer analysis of the site reveals that its focus seems to be on ghostwriting that aims to do the hard work for anyone short of time or skills.

Translation

The thing that the vast majority of Indonesian writers want above all is international reach. Fuelled in part by international writers’ festivals such as the UWRF and spin-off events such as the Makassar International Writers Festival, authors are increasingly keen to have their work available to English-speaking audiences.

Given the dearth of Indonesian-English literary translators, and the general reluctance of western publishers to publish literary translations, the role played by the Jakarta-based non-profit organisation Lontar Foundation is paramount. Established in 1987, Lontar’s primary aim is to promote Indonesian literature and culture through the translation and publication of Indonesian literary works. A recent player in the field of literary translation is InterSastra, an initiative founded in 2012 to improve and promote literary translation in Indonesia through workshops for those translating to and from Indonesian.

There is currently a very practical reason for the need for more translations of Indonesian literary works. In October this year, Indonesia will be the country Guest-of-Honour at the Frankfurt Book Fair, the world's largest. There, Indonesia will showcase its literary heritage, both traditional and contemporary, to Germany, Europe and the world. This has resulted in a flurry of literary translation activity. While there is an urgent need for translations into German, there are very few Indonesian-German translators, so for the most part this is being achieved by translation first into English, with secondary translation into German. The Indonesian government is supporting this through its Indonesian Translation Grant Program.

Writing in English

A very small number of Indonesian writers choose the English language as their medium. Richard Oh, co-founder of the Khatulistiwa Literary Award, wrote three novels in English inspired by the complex role of the Chinese in Indonesia, particularly after the anti-Chinese events of 1998. Poet, novelist and food-writer, Laksmi Pamuntjak, has published poems and short stories in English, and also publishes in Indonesian.

The most important writer in this regard is Maggie Tiojakin whose debut 2010 novel, Winter Dreams, was written in Indonesian. While the English translation has yet to be published, Maggie has made such an impression with her first novel and her success as a teacher of creative writing that she has landed a contract with Penguin Books for the publication of her next novel, which she is writing in English.

In September–October 2014, Maggie was part of ‘Island to Island’, a roving writing residency supported by Asialink Arts and the Melbourne Emerging Writers Festival. She was joined by fellow Indonesian writer, Ninda Daianti (who also writes in English), and Australian writers, Gillian Terzis and Andre Dao. The project took place in multiple locations across Indonesia, following an itinerary driven by their creative and professional interests, meeting other authors and artists and exploring Indonesian culture.

There are so many stories to be told in and about Indonesia, and the task of doing so currently lies largely in the hands of young Indonesians, fresh out of school, winners of local literary competitions who crave the glittering prize of a gig at an international writers’ festival. They face many challenges: how to weave local content into a story told in the national language, how to achieve the international exposure that is now a hallmark of literary success, and, crucially, how to get other Indonesians to read their work.

Pam Allen (Pam.Allen@utas.edu.au) is Associate Professor of Indonesian and Associate Dean (International) at the University of Tasmania.