Julian Millie

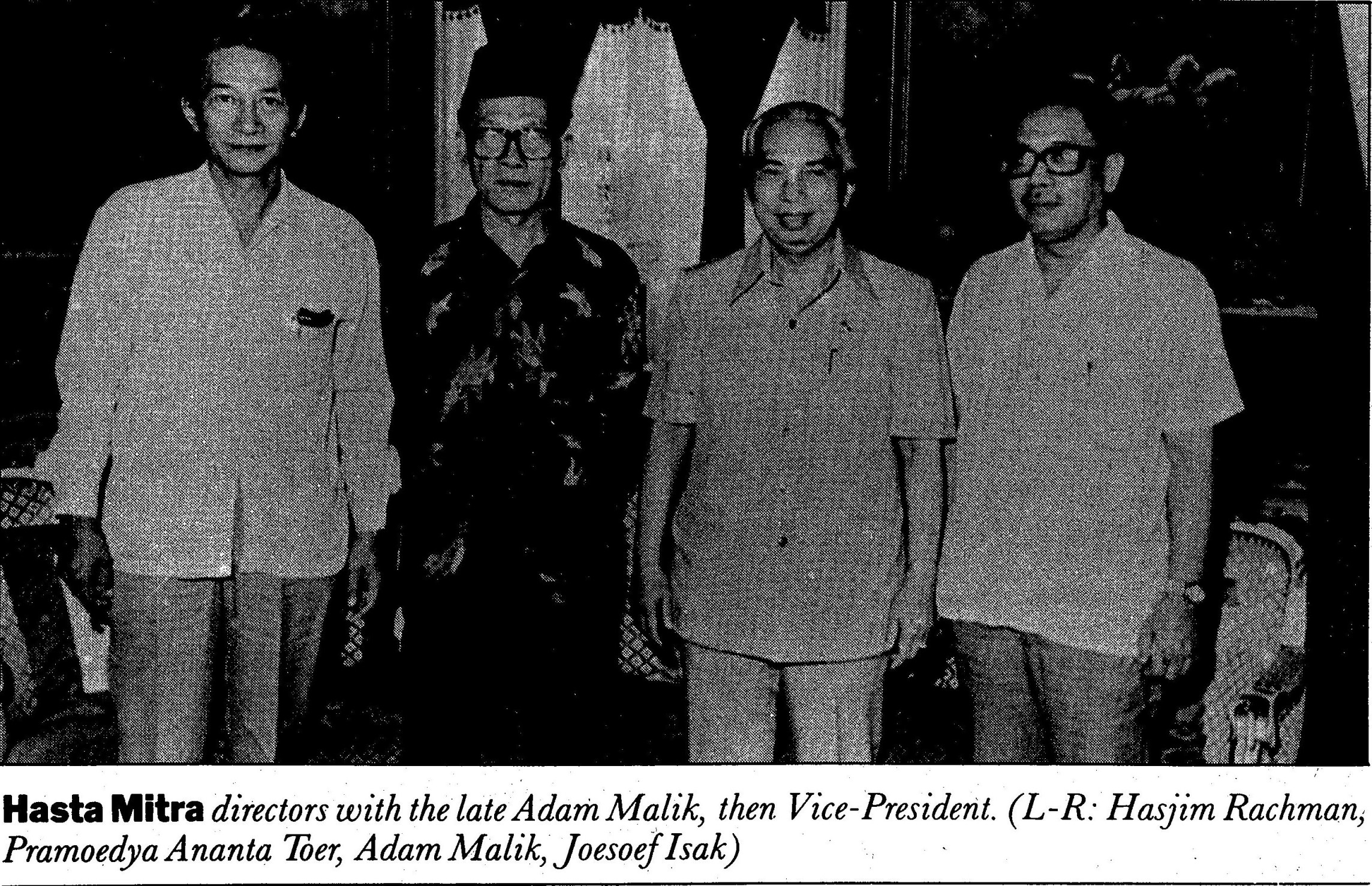

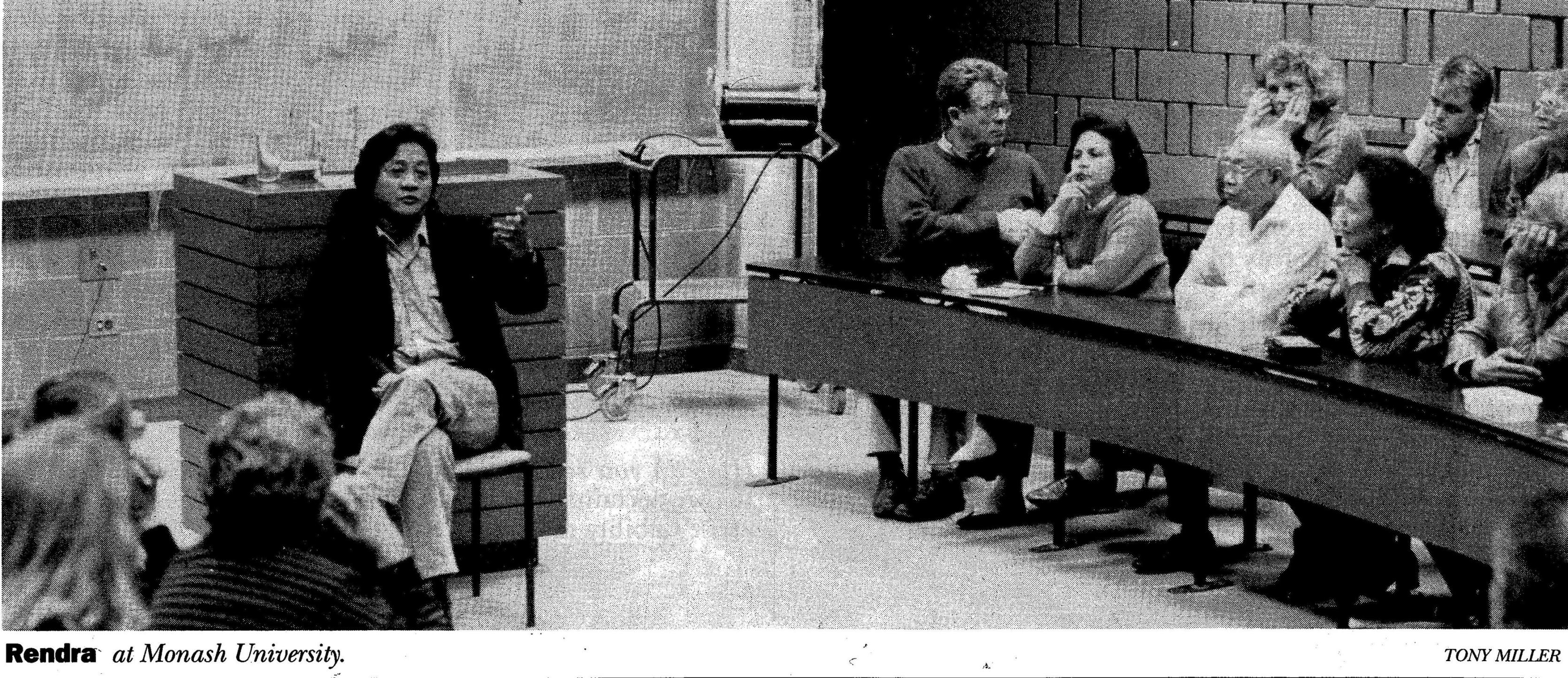

There was a time when Inside Indonesia represented Indonesian writing through a clear and focussed lens. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, writing was a means for critiquing Indonesia’s authoritarian regime, and some writers became victims of that authoritarianism. The magazine paid ongoing attention to two such writers, A.S. Rendra and Pramoedya Ananta Toer, and as a result of this attention, Inside Indonesia contains a valuable legacy of translations, interviews, reports and reviews. Australian academics including Keith Foulcher, Barbara Hatley, Max Lane and David Hill published translations of works by Rendra and others, which appeared in the rubric called ‘The People’s Culture’.

This coverage did not focus solely on the writings of Rendra and Pramoedya. It also gave attention to the censorship imposed upon them. The travails of Pramoedya’s publishers were described as they unfolded. Rendra’s incarceration and brushes with the authorities were reported in detail.

Indonesia’s contemporary literary scene has little resemblance to the picture conveyed by Inside Indonesia in the 1980s and 1990s. Contemporary writers’ lives do not provide the serious drama of the lives of Rendra and Pamoedya. Rather, as Pam Allen describes in her contribution to this edition, Indonesia’s successful writers, like successful writers elsewhere, enjoy an international circuit of festival appearances. Furthermore, how seriously are we to treat writers when they enjoy such brief shelf-lives? As Meg Downes explains, the commercial interests that underpin publishing and its spinoffs require a rapid turnover of authors and stylistic categories.

The comparison throws up some difficult questions: through what frame are we to approach Indonesian writing in the present? Now that Indonesia has moved beyond its authoritarian period, how do we know which literature should be written about in Inside Indonesia? How do we know what is important?

Inside Indonesia sought answers to these questions by asking six experienced researchers to write about a manifestation of contemporary Indonesian writing. Taken together, the writings collected and presented here suggest two answers. First, the days when big ideas about the national collective were found in something called ‘Indonesian literature’ are probably gone. Second, writing in forms outside of the conventional literary genres (in this edition we look at t-shirts, comics, and palm-leaf) is constructing collectives in surprising ways. These collectives, as Hendrik Maier notes in his contribution, are beneath the level of the nation. Against this background, there is much to be gained by taking a brief overview of contemporary Indonesian writing.

Writing against globalisation

The increasing reach of non-Indonesian cultural genres into Indonesia has inspired counter-moves in the form of revitalisations of indigenous ones. Seno Gumira Ajidarma describes contemporary efforts to reintroduce the work of Indonesian comic masters of the past. Indonesian comics of today reflect global styles. Their representations of characters’ bodies, for example, have been colonised by the muscularity of American super-heroes. As Seno puts it, ‘the warrior nobles of the wayang look like gym-instructors’. Japanese manga styles have been a second irresistible influence. But lovers of Indonesian comic styles have rallied, carefully republishing works by Indonesian comic artists. As a response to manga, this struggle is new, but as a dispute over the representation of Indonesia’s Indic influence, it is an ancient one.

Australian academics including Keith Foulcher, Barbara Hatley, Max Lane and David Hill published translations of works by Rendra and others, which appeared in the rubric called ‘The People’s Culture’. (Photo: Inside Indonesia)

Australian academics including Keith Foulcher, Barbara Hatley, Max Lane and David Hill published translations of works by Rendra and others, which appeared in the rubric called ‘The People’s Culture’. (Photo: Inside Indonesia)

Bali has been the site of considerable anxiety over identity and community values in recent decades. Our edition suggests two distinct responses, differing in the way they approach the past as cultural legacies. Andrea Acri’s account of contemporary lontar (palm-leaf manuscript) practices points to something that is indisputably true for all Indonesian ethnicities: classical writing genres are invested with high civilisational values, and are valuable resources for expressing ethnic distinction. Balinese respond to the wealth of learning stored in lontar manuscripts. This is not so surprising. But what is surprising is the emerging relationship between lontar and technology. Lontar is a writing technology that predates by centuries the most fundamental innovation in the field of symbolic expression: print publishing. Yet lontar and its production techniques have not only survived waves of technological innovation; those waves have in fact enhanced the value of the medium for Balinese. On Bali, new technology has been adapted not to replace the legacy, but to assist in its storage, preservation and dissemination. As a result, the range of lontar titles is expanding.

Emma Baulch’s reflection on Nanoe Biroe’s project of ‘populist cosmopolitanism’ is a perfect partner to Acri’s update on lontar. The lontar is a concentrated symbol of learning and civilisation, to the point where it might obscure other, less refined symbolic forms. T-shirts for example. What is surprising about Biroe’s t-shirt message project is his use of low Balinese. The lower registers of Indonesia’s regional languages have traditionally been considered good for only one thing: everyday communication. But contemporary unease over identity within Bali demands more than reinvigorations of the religious canon. Nanoe Biroe’s low Balinese expressions form an inclusive and cosmopolitan national project, Emma suggests, something that cannot be easily achieved through the high culture genres.

Telling one’s own stories

Maier’s article provides a vista on the amazing inheritance Indonesian writers have left contemporary Indonesians. But his view into the past does not yield a clear picture. Maier’s central observation is that the Indonesian nation can no longer serve as a unifying basis for an overview of writing. Rather, dispersed interests are served by the high velocity multiplication and fragmentation of genres.

Meg Downes gives some detailed texture to this multiplication. At the end of the Suharto period, the Indonesian publishing world was changed by the emergence of a cohort of female writers whose work drew attention to ‘women’s emancipation from stereotypical gender roles’. Not even 25 years on, the wheel of novelty has turned again, and the latest cohort is self-consciously Islamic and/or a teenager. Meg highlights the ambiguity in this rapid turnover of trends. When teenage women writers open up spaces for telling their own stories, our first reaction might be to applaud this as a beneficial expansion of public expression. But at the same time, the cycle by which a novel is transformed into a feature film points to the large capital that underpins the production and exploitation of Indonesia’s younger female authors. Opening up new spaces for expression is also big business.

But writing does not require capital, and it does not even need readers. As Pam Allen explains, social media has enabled anyone with access to the internet to become a writer. One can tell one’s own story free of the obstacles arising in the conventional publication process, whether one’s story is shaped by regional identity, ethnic membership, or religious affiliation. With the help of an expanding range of online platforms, all writers can be part of…part of what exactly? As Henrik Maier tells us, contemporary Indonesian writers are not continuing the lineage of Indonesian writing. Rather, this collection makes it clear that the writers recalling the past with a strong sense of purpose and linear continuity are doing so from within sub-national identities.

Julian Millie (Julian.Millie@monash.edu) is senior lecturer in anthropology at Monash University.