Kathleen Azali

In recent years creative economy, creative industries and creative cities have become buzzwords in Indonesia’s big cities, noticeably targeting youth. Filling talk shows, competitions, workshops and magazine articles, these concepts have become familiar to the point of being overused. Today, they are even being adopted in political campaigns and inspire new study programmes in academic faculties.

Targeting a specific segment of Indonesia’s urban youth population that is educated, increasingly cosmopolitan and media-savvy, the creative economy campaign promotes alluring images of young, modern, educated, mobile ‘no-collar’ workers who view their jobs not just as livelihood, but as a fulfilment or expression of personal aspirations—not only for themselves but also for their community. They come to the office—or work from home or café—wearing casual apparel they like, view their co-workers as close friends, and happily work hard through extended hours to achieve high-quality output.

These trendy images clearly resonate with some youth, who are attracted by the sense of freedom and global connectedness that they associate with a career in creative industries. Yet, behind these images, the realities for young people in creative industries often consist of freelancing individuals and small enterprises with low and unpredictable profits. This raises questions about the quality of education and information that will help young people develop their skills and knowledge, as well as the exact avenues of youth entrepreneurship that this campaign promotes.

A silver bullet?

The government campaign for creative industries is supported by two key demographic and socio-economic trends in Indonesia. One is the rise of the much-touted middle class with its promise of stronger purchasing power and domestic consumption. The other is Indonesia’s relatively youthful population. Currently, roughly half of the total population is below thirty years of age (123 million). If this young population is equipped with suitable work skills and aptitude, a ‘demographic bonus’ of a productive population is often predicted, bringing significant opportunity for economic development. Seen this way, young people are valued as both consumers of global youth culture and as producers who could deliver tangible products to be marketed under the creative economy framework.

Discussions at policy level on creative economy and creative industries started gaining momentum in Indonesia during Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s presidency. During this time the Ministry of Culture and Tourism doubled as Ministry of Tourism and Creative Industries, headed by Mari Elka Pangestu, previously the minister of trade. Roughly a decade later, under Joko Widodo’s (Jokowi) presidency, the sector has been removed from the remit of the Tourism Ministry. Instead, a new Creative Economy Body, headed by Triawan Munaf, has been established. In developing its policy framework for creative industries, the Indonesian government has worked closely together with the UK government’s Ministry of Culture, Communications and Creative Industries, signing an agreement of cooperation in 2012.

The government defines the creative economy as one that ‘intensifies information and creativity by relying on ideas and stock of knowledge of its human resources as the main production factor in its economic practices’, whereas creative industries are ‘those industries which have their origin in individual creativity, skill and talent, and which have a potential for wealth and job creation through the generation and exploitation of intellectual property and content.’ Thus, income is generated not only from the sales of goods and provision of services, but also the licensing of intellectual properties - for example, licensing of music, movies, product design, and so on.

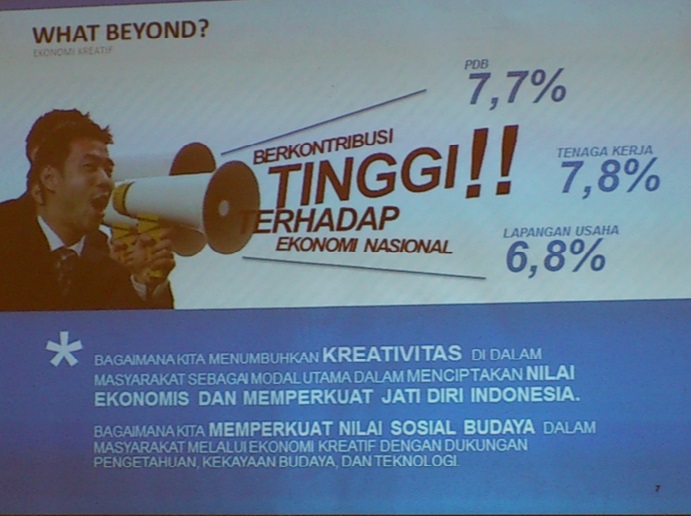

In 2005, the category of creative industries encompassed 14 subsectors: architecture, design, fashion, film, video, and photography, crafts, computer and software, music, art, publishing and printing, advertising, interactive games, research and development, performing arts, television and radio. In 2011, culinary industry was introduced as the 15th subsector, thereafter significantly boosting the share of creative industries to the national GDP. The 16th subsector, digital application and game developing, was added in early 2015. While the number has slightly decreased following the slowing growth of GDP in Indonesia, the growth of the creative economy sector in Indonesia is still claimed to be higher than the national growth.

Promoting youth entrepreneurship

From a government perspective, the creative industries sector is attractive not only for the potential revenues it could generate, but also for providing an avenue for young people’s entrepreneurship. Reflecting a common sentiment, former Minister of Tourism and Creative Industries, Mari Elka Pangestu, was quoted saying: ‘Youths are highly influenced by the latest trends and global styles and are connected to social media’. In her view, this makes young people the driving force behind the creative industries: ‘They have the energy and creativity to develop local knowledge and traditions.’

But despite the fashionable, stylish portrayal, youths who are interested in the creative industry still face problems similar to any other industry in Indonesia such as unevenly distributed transportation and communication infrastructure, bureaucratic inefficiency, and widespread problems of corruption.

As an industry that relies on the ‘ideas and stock of knowledge of its human resources’, creative industries are highly dependent on the skills and knowledge of educated and creative youth. In recent years, new departments in creative industries and design have been rapidly established in universities and vocational secondary schools of various reputes and credibility across the nation. These schools help to promote the idea of creative industry as a viable career option for youth and their parents. However, the realities in these schools often contrast with the glossy advertisements that promote these new study programmes. Except for a limited few, most schools and colleges are barely equipped and experience a lack of skilled teaching staff and facilities. Not many schools and colleges have up-to-date references or access to journals, while accessible public libraries, archives, or museums that introduce local arts, tradition and knowledge barely exist.

A design fair held in Surabaya Town Square mall, where young people can rent a booth to display and sell their designs - Erlin Goentoro

A design fair held in Surabaya Town Square mall, where young people can rent a booth to display and sell their designs - Erlin Goentoro

A graphic designer who graduated with a degree in visual communication and design from Surabaya recollects some of these problems: ‘The same lecturer would be teaching different classes after classes. There were plenty of classes without any lecturers or tutors showing up.’ Reflecting on the curriculum and teaching materials he adds: ‘Forget the library, you'll have more luck browsing bookstores or lifestyle magazines to get some ideas. Luckily these days you can get plenty of references through the Internet. The curriculum did not prepare me for the job, but I did get introduced to people with related interests, and this brought some opportunities for the future.’

Likewise, another young designer who has studied in Surabaya before he pursued a higher degree in Bandung notes: ‘I didn't really learn much from the formal classes, but my campus in Bandung has a very strong network with established connections to government and companies. So that created more opportunities for me to gain the skills and practical experiences outside campus.’ These examples suggest that the value of these new design majors lies perhaps not so much in the knowledge they provide, but more so in the opportunities for students to build a personal network that will help them with a future career in creative industries. These personal networks of friends, family and acquaintances are equally important for young people’s efforts to set up a business in creative industries.

Freelance work and business start-ups

For many youths, their interest in creative industries usually begins as a casual experiment or hobby. They often start their business without any clear business plan or legal foundation. When lacking capital, they usually turn to family or friends for support. Often they depend on facilities provided by their parents, family, friends, campus, or their workplace, for the provision of a workspace, computer or internet access enabling them to promote their products or services. Creative workers may also use their private space at home or in a boarding house, borrow a smartphone or vehicle from a friend, or allocate part of their college tuition fees to fund production costs.

Starting up a business in creative industries comes with risks of irregular or 'flexible' working hours and irregular income. These conditions are certainly nothing new among youths trying to find work in Indonesia. The problem, however, lies in the innocuously apolitical message of the creative industries campaign used to mobilise youth career and lifestyle expectations. The basic tenet of creative industries as relying on seemingly immaterial ‘ideas and stock of knowledge’, often conceals the considerable investment of time, capital and material needed to develop the necessary skills, knowledge and reputation. Web developers, baristas, filmmakers and designers may hail from disparate industries, but they do not develop their skills and reputation overnight. They have to research and invest in their tools, buy their computers, cameras, software or coffee makers, and hone their skills through years of training and work experience.

Although work skills and aptitude of creative youth might be comparable across different regions, the most favourable infrastructure for digital start-ups is found in Jakarta, Bandung and surrounding areas. Jakarta dominates the potential access to capital, clients, multinational funding organisations, and even Internet and electricity. All international media bureaus that can give valuable exposure to global markets are also located in Jakarta.

Official campaigns do not pay sufficient, if any, attention to questions about digital divide, unequal opportunities and precarious working conditions. Within creative economy campaigns, precarious conditions tend to be overlooked, or even sugar-coated as barriers that must be overcome with creative tenacity. As a model for new modes of living and working to aspire to, ‘creative’ is thus a very exploitable concept. As a friend jokingly but succinctly said: ‘If you live in Indonesia, with its famously unreliable government support for infrastructure, you have to be creative or kere aktif (poor but active)’, meaning that people have to build or be their own infrastructure amidst such uncertainties.

Selling cool places

The government’s failure to provide adequate infrastructure forces young people to be more ‘independent’ and entrepreneurial. Indonesia’s creative sector is famous for its Do-It-Yourself (DIY) culture. Bandung, the first city anointed as Creative City in Indonesia, has long been known for its vibrant music and fashion subcultures, which form the basis of various creative events and sites, including festivals, distros (fashion distribution outlets) and cafes. These diverse expressions, later tied together and branded as ‘creative city’, attract not only large student and youth populations, but also domestic and international tourists.

But as the cool, ‘creative’ factor of a site increases, property price hikes and big players usually follow, particularly since the deregulated, liberalised real estate market has grown dramatically in the past decade. With land prices climbing up to 100 per cent per year, in Bandung many of the original fashion and music distros, founded in the late 1990s and early 2000s, along with other small and medium enterprises, now have closed or can barely sustain themselves, as they face aggressive competition with new factory outlets, boutiques, hotels or cafes owned by property developers, textile suppliers, or other business groups with larger, sometimes global capital.

This phenomenon is increasingly common in other cities as well. In less than a year, Pasar Santa in Jakarta, once a neglected traditional market, has seen its rental price increased to more than 100 per cent after young people started opening various creative businesses like cafes and vinyl stores, attracting public and media attention along with estate speculators. As developers and real estate rush to find the next cool space to invest in, many of the original tenants and youths that have produced the cool, creative image in the first place are squeezed out of the strategic, formerly affordable venue to experiment or develop their creative work.

The government may be actively promoting a creative economy and creative industry, and think of them as good promotional or branding tools for the country, or as ways to prepare its youth population for the regional and global market. But after almost a decade of planning, doubts have started to creep in about the promises of creative industries compared to their less stylish counterparts. The campaign for creative industries has indeed helped to boost the status and knowledge of local products and talents, and perhaps allows some young people to make a living from what they aspire to. However, to ensure sustainable and inclusive growth, efforts to promote creative industries need to move beyond novelties, flashy images and packaging, to address unresolved structural issues such as the digital divide, infrastructural problems, unequal access to education and information, access to capital, and unstable real estate markets.

Kathleen Azali (k.azali@c2o-library.net) founded C2O library & collabtive, a collaborative lab based in Surabaya, Indonesia. She works as a research associate at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS), Singapore. She is currently involved in a six-month research project on creative cities in Indonesia funded by the British Council. The contents of this article, nonetheless, reflect her personal views.