Tim Flicker

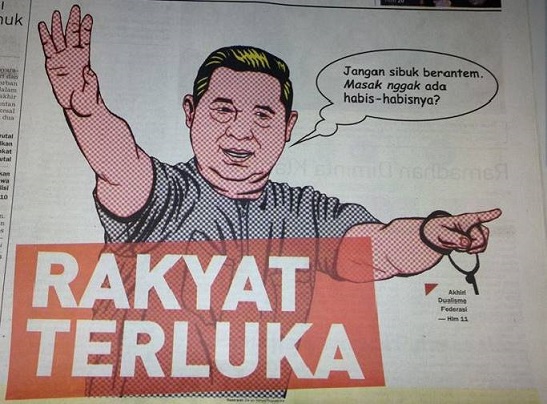

Republika, March 6, 2012. ['The Nation's Pain: Stop your constant fighting. Is there really no end?']

On 29 February 2012, the Indonesian men’s national football team faced Bahrain in a World Cup qualifier leading up to the 2014 World Cup. To every one’s surprise, Bahrain won the match 10-0, in the process inflicting on Indonesia the country’s worst ever international defeat.

Indonesia’s humiliation didn’t stop there. Immediately after the match, the international football body FIFA, concerned about the validity of the result, launched an investigation into the team. Curiously, though, the international scandal received little attention in Indonesia. Initial responses were swift, and indicated that the media were serious about exposing the match as a case of possible corruption. Both Kompas and Republika ran front-page stories to that effect.

But that momentum was quickly lost. Subsequent coverage of the match focused on the humiliation experienced by the Indonesian nation as a consequence of the team’s biggest ever defeat. Where allegations of corruption were made, they predominantly referred not to the Indonesian team or the governance of Indonesian football, but scapegoated the Lebanese referee, Andre El Haddad. And just a week after the match reporting had all but stopped.

The inquiry should have drawn attention to the problems facing Indonesian football. But instead the media – and the nation – chose to look the other way. Indonesians live and breathe the world’s most popular sport and this apathy frustrates their ambition to achieve international glory.

A national disgrace

Unlike in badminton, where Indonesia more than holds its own, Indonesian football has never achieved sustained success at international level. In fact, leading into the Bahrain match, Indonesia had no chance of progression to the next stage of qualification as the team had conceded 16 goals in the first five matches, and scored only three. Most significantly, coming into the 2012 match, Bahrain needed at least nine goals to have any chance of reaching the next round of World Cup qualifiers.

It would be naïve not to suspect something more sinister was at play here than sheer brilliance by Bahrain, which explains FIFA’s decision to launch an inquiry. The deeper question, however, is why Indonesia – a huge country with a massive football following – performs so poorly at the international level?

An important part of the puzzle is the impact of a long-standing political power struggle between the Indonesian Football Association and the Committee to Save Indonesian Football. As a consequence of this struggle, national-level competition was divided between the Indonesian Premier League and Indonesian Super League. Only players from the premier league were able to play for the national team at a time when many of Indonesia’s best and most experienced players were involved in the Indonesian Super League. Consequently, for years the national team was essentially an under-23 side.

The conflict between the two bodies has now been resolved, resulting in the Indonesian Super League becoming Indonesia’s top competition. But allegations of match-fixing and other forms of corruption continue to be major obstacles to establishing international credibility. The documentary Duit, Dukun dan Dingklik documents what is widely referred to as a ‘referees’ mafia’, tracking the rise of the local East Javanese team Persik Kediri. Interviews with the club manager, a supporter, a journalist and the local mayor, who is also owner of the club, leave viewers with little doubt about the extent to which corruption permeates the domestic leagues. Meanwhile, the former chairman of the Indonesian Football Association, Nurdin Halid, has continued to run the association from his prison cell.

More than two years on, the outcome of the match-fixing inquiry for the Indonesia-Bahrain game is yet to be released. In fact, it appears unlikely that any investigation will ever be properly conducted. The Indonesian and Bahrain teams, the media, and even FIFA, seem content to move on – leaving Indonesia’s football community no better placed to deal with its deep-running sore of corruption.

Media failure

The media’s failure to pursue the World Cup case is symptomatic of a broader problem. Media freedom has expanded, but investigative journalism and in-depth analysis are still sadly lacking. Moreover, while corruption is reported on a daily basis in Indonesia, the reporting of sports corruption is comparatively weak. Without a more diligent and investigative media, the problems within Indonesian soccer are sure to continue and future international success will remain elusive.

It is time that the Indonesian sports media simply stopped accepting ‘unsual results’, and actively investigated claims of corruption and mismanagement within Indonesian football. Otherwise the national team will struggle ever to achieve its potential, which would be a terrible pity for Indonesia’s hundreds of thousands of football fans.

Tim Flicker (tim.flicker@hotmail.com) completed Honours in Indonesian Studies at Monash University in 2013.