Keith Foulcher and Barbara Hatley

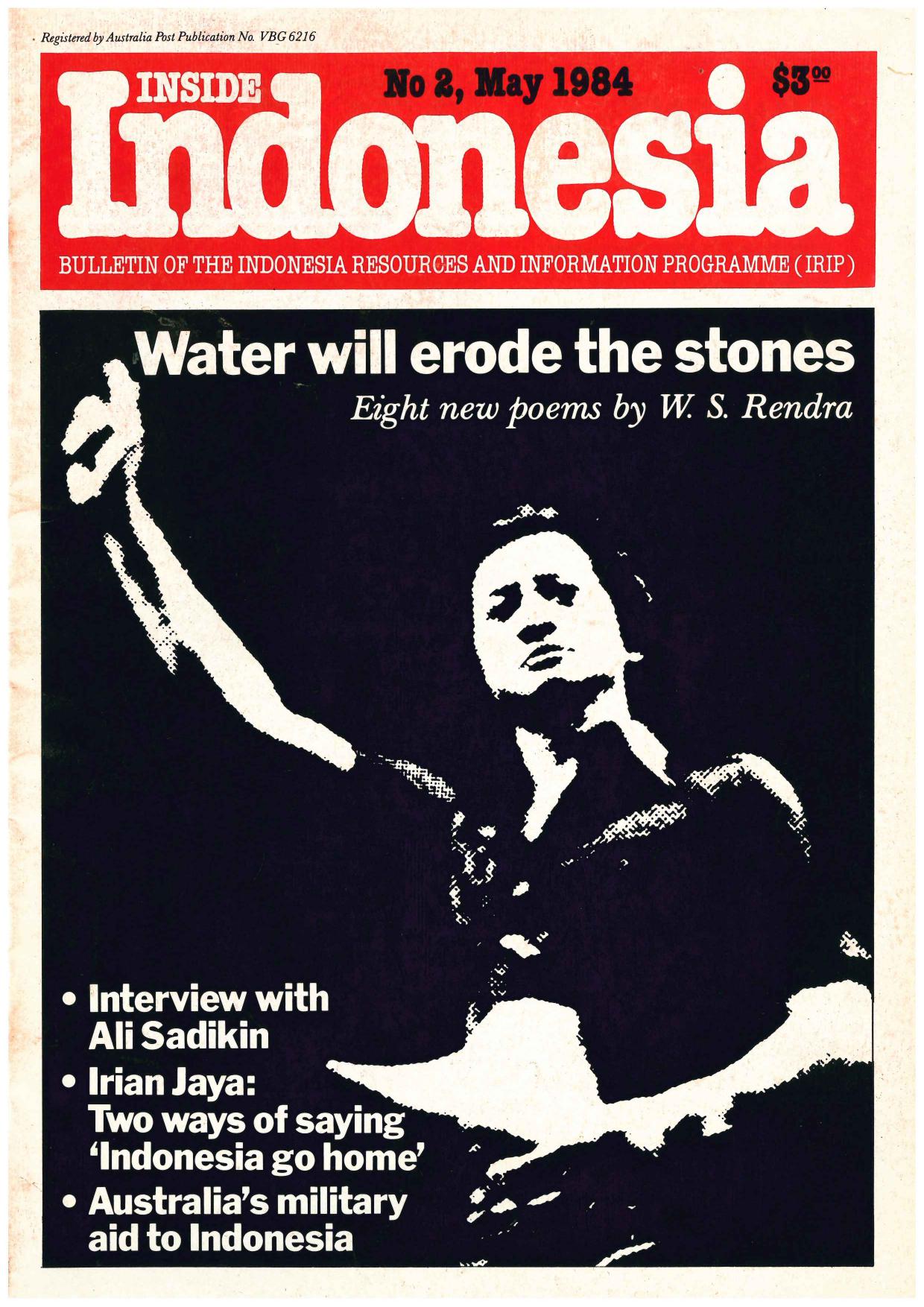

Cover of Inside Indonesia No. 2, May 1984

Recent articles by some of the founders of Inside Indonesia have reminded us that when the magazine was founded in 1983 it was part of a broadly-based movement working for political and social change. Its brief was to expose the negative impacts of developmentalism on the lives of the poor, and the denial of civil and political rights to the opponents of the New Order regime. The tone of the magazine was activist and alternative, and most of its articles were authored by non-Indonesians from NGO or academic circles in Australia with links to oppositionist groups ‘inside’ Indonesia itself.

From the start, reports on the Indonesian arts reflecting this orientation figured prominently in the magazine’s content. The second issue of Inside Indonesia, in May 1984, featured a cover design based on an image of the poet Rendra, with the caption, ‘Water will erode the stones Eight new poems by W.S. Rendra’. During the next thirty years, however, this orientation was to undergo a significant shift. Both reporting on the arts and culture in Inside Indonesia and the character of the magazine itself changed, in line with the dramatic transformations taking place in Indonesian social and political life at this time.

‘The People’s Culture’

A key emphasis in the early issues of Inside Indonesia was on the role of literature, performance and the visual arts as a forum for critiquing and attempting to undermine the power of the New Order regime. Articles like Krishna Sen’s ‘Sjuman Djaja, a film maker as social critic’ in December 1985 and Rosslyn von der Borch’s ‘Poets against silence: Two young Solo poets’ in October 1987 showed just how significant and widespread oppositionist and subversive expression was in the Indonesian arts at the height of New Order rule. Another theme in the articles of this period is the ability of artistic expression to represent, communicate with and empower ordinary people. Barbara Hatley’s ‘Women in popular Javanese theatre’ in April 1987, for example, reported on contemporary theatre groups in kampung neighbourhoods, describing their rehearsals and performances as participatory activities ‘through which people can express their views and help perpetuate their own culture’.

Both these understandings of the role of the arts – political opposition and representation of the lives of ordinary people – are encapsulated in the rubric for the cultural segment of Inside Indonesia during this period, ‘The People’s Culture’. This phrase has strong associations with the cultural politics of the late Sukarno era, and its use in Inside Indonesia up until the mid-1990s reflects the magazine’s links at this time with the legacy of the pre-1965 left. Victims of the post-1965 purge of left wing artists feature prominently among the writers whose poetry and short stories were translated in the pages of the magazine, and numerous articles highlighted the role of Pramoedya Ananta Toer, who had been released from prison in 1979 but was still being held under virtual house arrest in Jakarta when the magazine was in its early stages of development. Interviews with Pramoedya and his publishers on the banning of his books, the reasons why his historical novels challenged and disturbed the authorities, and his views on contemporary human rights, all featured prominently.

Taken as a whole, the first two decades of Inside Indonesia’s publication documented an important chapter in the cultural history of late twentieth century Indonesia. The articles on culture appearing in the magazine at this time remind us that from the early 1980s right up until the end of the New Order period, there was a vigorous current of anti-establishment and anti-regime expression in the Indonesian arts. This is an important corrective to some retrospective characterisations of the New Order as a totalitarian and all-embracing state system that exercised tight control over every aspect of Indonesian life. ‘The People’s Culture’ shows that in the arts, as in many other areas, this was never the case.

Diversity and inclusiveness

In the late 1990s, as opposition to the New Order broadened and intensified, Inside Indonesia began to diversify its reporting on Indonesian cultural expression. Positive-themed articles on topics like the presence of women in the traditional and popular arts, the burgeoning of a rebellious youth culture and an expanding pop music scene, began to supplant the more critical and political content of the articles of previous years. The alternative and oppositionist nature of much of this reporting remained, but the tone lightened, and the range of topics covered in the articles began to broaden. David Hill and Krishna Sen epitomised the change in their 1997 article on rock and pop music, with its view of popular music as ‘a gesture of generational opposition to [an] ageing regime, led by an old man’.

When the Reform Era exploded with such force in May 1998, Inside Indonesia was soon documenting the new opportunities for creativity and the expression of identity that had been opened up by political reform and a freer social climate. Freed from fear of retribution, Indonesian authors writing under their own names became more prominent among the magazine’s contributors. For example, Indonesians with connections to the film industry began writing about new, independent films, and brought the existence of films dealing with real-life and often controversial social issues like same-sex relationships and religious divisions to the attention of the magazine’s growing number of subscribers. The flourishing of women’s artistic activities, particularly the new wave of fiction writing dealing frankly with sexual issues, also made its presence felt. Reports on new work by women visual artists and theatre productions by women directors and female actors voicing women’s concerns, foregrounded the role of women in Indonesian cultural activity at a time of political reform.

A special issue on culture in 2000 highlighted the participatory, socially-involving character of the Indonesian arts in the early Reform Era. It contained articles on, among other things, the building of community identity through an arts forum in Makassar, the role of underground music in providing a sense of belonging for young people, and the way the Central Java arts collective, Taring Padi, was using the new social freedoms to create lively community networks. The tone of these articles is celebratory and optimistic, reflecting the hopes for a better future that were ushered in by the fall of Suharto and the New Order regime. The Indonesian arts of this period were testing their new freedoms and Inside Indonesia opened its pages to their experiments. In many cases cultural activity shifted to the grassroots and became more playful, and Inside Indonesia followed suit. The cheeky title to an article by Marshall Clark and Giora Eliraz in 2002, ‘Reformasi killed the poetry superstars’ captures the mood of the times.

Amid the euphoria, however, Inside Indonesia never lost its critical edge. In the 2000 special issue on culture that celebrated the new freedom of artistic expression, Lauren Bain expressed some disquiet about the ‘loss of direction’ which the more outspoken currents in Indonesian theatre seemed to have undergone with the demise of their New Order targets. And by the end of the first decade of the Reform Era, the magazine was reporting on new political pressures being experienced by the arts and arts practitioners in many regional areas of Indonesia. A 2008 article by Jennifer Lindsay questioned the reality of the climate of freedom in the arts, citing the ongoing need for performance permits in some regions and vigilante attacks on artists, especially in areas where militant Islamists were exercising unofficial censorship of artistic expression. Yet at the same time, reports continued to appear on the positive contribution of particular arts activities to their local social environment. More than ever before, Inside Indonesia was representing the world of the Indonesian arts in all its diversity and complexity.

Looking back

In the three decades since Inside Indonesia’s inception in 1983, Indonesia has moved from a politics of authoritarianism and repression of dissent to one of democratisation, with its own complexities and tensions. As part of this process, political opposition through expression in the arts has given way to a more broadly-based conception of the role of the arts in mediating the imaginative lives of communities and individuals and their social, cultural and political identities. At the same time, Inside Indonesia has itself moved from being an activist magazine dedicated to the struggle for political change to a channel for information on issues related to human rights, the environment, and the many political and social challenges to the wellbeing of Indonesia and its people. Times change and so does culture. Inside Indonesia has been both a reflection of that change and an active participant in it.

Barbara Hatley (Barbara.Hately@utas.edu.au) is Professor Emerita of Asian Studies at the University of Tasmania. Keith Foulcher (Keith.Foulcher@sydney.edu.au) is an Honorary Associate of the Department of Indonesian Studies at the University of Sydney. Both have been contributors to Inside Indonesia and members of its editorial collective since its inception.