Julie Chernov Hwang

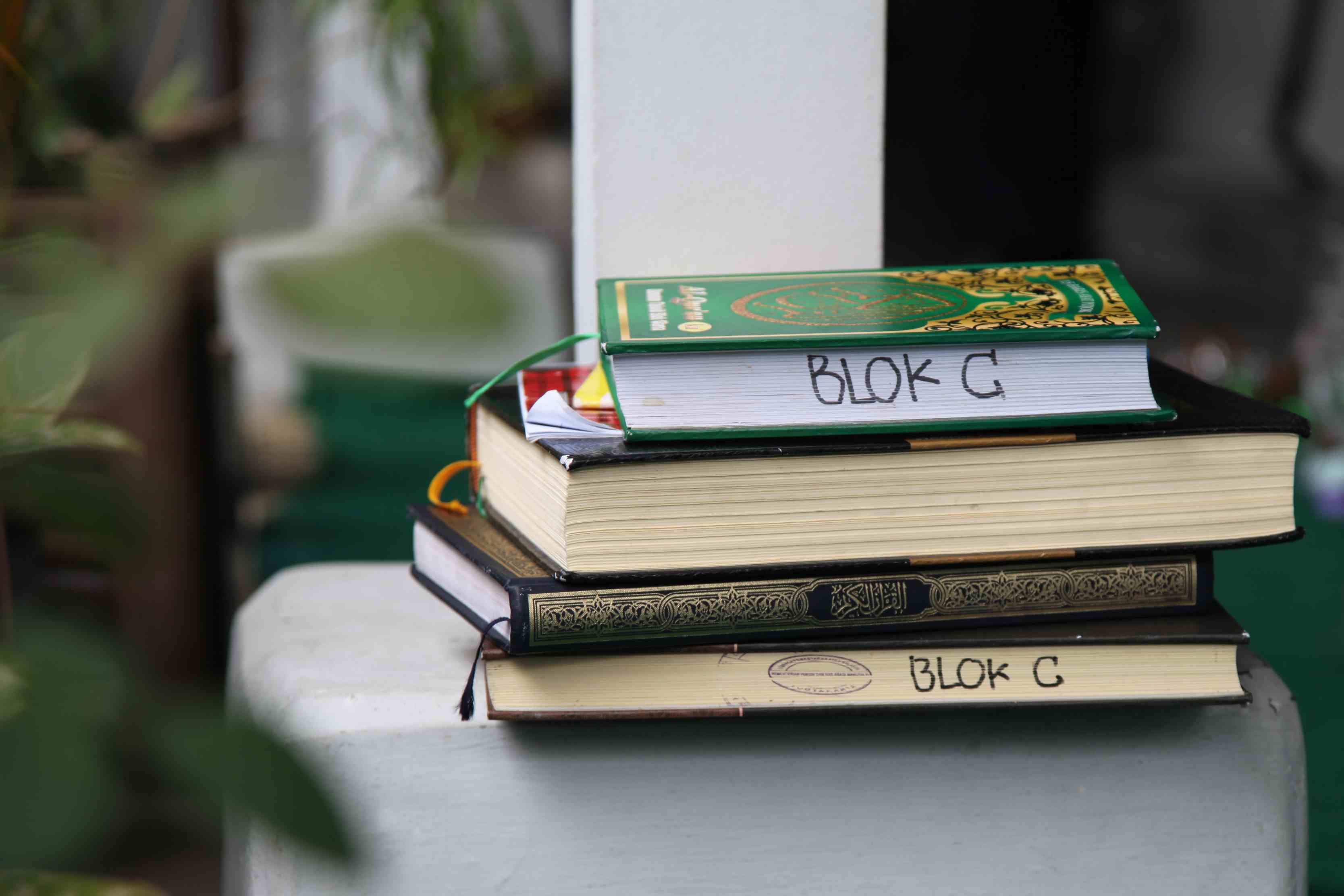

Teaching the Koran in prison provides Ahmed with a sense of purpose - Nikki Edwards

Several years after his participation in the Tentena market bombing, the Posonese jihadi ‘Ahmed’ surrendered himself to the police counter-terrorism team, known as Densus 88. He was sentenced to 15 years in prison, a term he began at the prison at regional police headquarters in Jakarta before being transferred to Petobo prison in Palu where he is serving out his time.

Now behind bars, like many other Posonese jihadis, Ahmed is turning away from terror. But while it might be tempting to champion Ahmed’s disengagement as proof of the rehabilitative properties of prison, the factors leading to Ahmed’s shift in behaviour and mindset are in fact far more complex.

Caught up in the conflict

Ahmed’s story is inextricably linked with the Poso conflict, which began as a series of tit-for-tat clashes between youth gangs that escalated into riots. Things quickly became even more serious in May 2000 when Christian militiamen attacked an Islamic boarding school and mosque on the road between Poso and Tentana. Christian fighters killed some 200 Muslims including women and children in what has become known as the Walisongo massacre.

In the weeks after the massacre, trainers and fighters from Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) began arriving in Poso at the request of a local hardline Muslim cleric, Adnan Arsal. They set up study groups (ta’lim) in the local mosques and affiliated with the local Tanah Runtuh community, which Arsal led. After several months of religious indoctrination, some ta’lim attendees were selected to participate in paramilitary training ‘courses’ at a camp outside Ampana. They were taught how to use firearms and other military tactics by JI trainers as well as a few select graduates from the first paramilitary training.

Although the Malino Peace Accords in 2001 marked the formal end of the communal violence in Poso, sporadic attacks on Christian civilians continued until January 2007 when Densus 88 raided a school and home in Poso’s Tanah Runtuh neighbourhood, which had served as a hub for militant activity in the area. According to the International Crisis Group, the raids resulted in the arrests of 20 militants and the deaths of 15 others, including 11 militants, a police officer, and three seemingly innocent bystanders. While the cost was high, the raids successfully disrupted the operation of the Tanah Runtuh cell.

Bombing Tentena

Before the 2000 Walisongo massacre, Ahmed spent most of his days hanging out in a gang, helping his brother in his computer shop, and drinking – behaviour that was not uncommon among Poso youths. After the Walisongo massacre many of Ahmed’s friends joined the ta’lim. A year later he too followed, motivated by his desire to learn more about Islam. Initially, his family welcomed his attendance at the ta’lim, seeing positive changes in their son. He stopped drinking and began reading the Koran. But then, after several months of indoctrination, Ahmed was selected to participate in paramilitary training. He soon decided to join with others in Tanah Runtuh who rejected the Accords and participate in revenge attacks targeting Christian civilians. This laid the groundwork for his participation in the bombing of the Tentena market in May 2005.

The Tentena market bombing was one of many terror attacks undertaken by a sub-grouping of the Tanah Runtuh members, often referred to as the ‘hit squad’. Led by Hassanuddin, a JI member who fought in Mindanao, these men sought to exact ‘street justice’ in revenge for the Walisongo massacre and other Christian militia attacks. The bombing of the Tentena market was part of this approach, designed to show they could penetrate a Christian ‘stronghold’. According to the International Crisis Group, 22 people were killed and another 70 injured.

Ahmed was one of the four hit squad members chosen to participate in the attack. He was not told why the marketplace was chosen. One of his teachers just approached him and asked him if he was ready to put what he had learned into practice. When he responded ‘God willing’, this was taken as consent and his teacher told him details would follow. Ahmed told me he was proud that he was one of four selected to participate.

After a year of attempting to negotiate the surrender of the militants responsible for this and other terror attacks, Densus 88 conducted two raids on the Tanah Runtuh complex on 11 and 22 January 2007, resulting in the deaths of 14 militants. Ahmed escaped during the 22 January raids and made his way home to his parents’ house. His parents begged him to surrender, but at first he refused. When he saw his parents crying, he decided to give himself up. He was soon tried and sentenced to 15 years for his role in the bombing.

Disengaging

While many jihadis are further radicalised by the relationships they form in prison, incarceration had the opposite impact on Ahmed. By the time I interviewed him in Palu, Ahmed no longer considered himself a member of Tanah Runtuh. He had adopted a position common to mainstream JI members, namely that Indonesia is not a legitimate field of jihad at this point in time.

His initial incarceration in Jakarta gave Ahmed the time and space to reflect on his actions. He read a great deal. Ironically, his experience in the JI ta’lim in Poso meant he had the Arabic language skills to teach the Koran to fellow prisoners, giving him a sense of purpose. His time in prison also allowed him to observe others. He realised that the police prayed too. After reflecting and discussing these issues with other prisoners including Ali Imron, the repentant Bali bomber, Ahmed began to change his thinking. Ultimately his attitude about the police, the state, the permissibility of his own actions and even the general applicability of syariah to Indonesia changed.

But it would be remiss to assume that prison made the difference for Ahmed. In fact, he had begun to disengage before he surrendered. One important factor was the reaction of his parents. Reflecting on their distress when he arrived home, Ahmed explained, ‘It was the first time I saw my father cry. Then, I followed the wishes of my parents. [Islamic doctrine says that] we have to show respect to our parents. Previously, I was unable to hear their words.’ For Ahmed, seeing his father cry for the first time made him question the ideological frame in which he had been operating. It reoriented him toward a different set of Islamic values that prioritise obeying parents’ wishes. This was common among many of the Poso jihadis I interviewed, including most of the hit squad members.

Surprisingly, Ahmed’s experiences with the police also influenced his move away from radicalism. During the interrogation period, he was treated humanely and provided with good food and a bed. This treatment was completely at odds with his expectations and assumptions. The approach was part of what Brigadier General Suryadharma Salim, then the head of Densus 88, termed ‘maintaining friendships’ with the suspects. This ‘soft approach’ included providing assistance to the families of the imprisoned and, for a brief period, facilitating marriages. In October 2007, Ahmed was able to marry his girlfriend, the cousin of a fellow militant. Densus arranged the transportation of his wife from Poso to Jakarta and they were married in the mosque at POLDA Metro.

Ahmed used to believe that the police were wrong in enforcing man-made laws over the laws of God. But his experience after his surrender made him realise that Densus members pray and are not ‘unIslamic’ or ‘inhuman’. He also came to believe that it was wrong for him to set off bombs because of the indiscriminate nature of such an attack. But Ahmed’s disengagement has not been absolute. Like all the Posonese jihadis I interviewed, he said that if the Christian militias attacked again, he would take up arms. But he drew a distinction between his current perspective and his past attitude. ‘If [the Christians] disturb me and other Muslims, conflict may break out again. However, in the past, I attacked them whether they initiated it or not.’ Interestingly, while other Posonese jihadis assumed that the Christians would attack again at some point, Ahmed mentioned no such belief. Instead, he contended that unless the Christians attack, it was likely Poso would stay peaceful, since his ‘brothers’ are too busy running businesses to involve themselves in violence.

Ahmed still has nine years of this sentence left, which he will serve out in Petobo Prison in Palu. His wife currently works at the Population Office on a contract-by-contract basis in order to support herself and their son. Ahmed spends his days reading and teaching the Koran. In the past, he admitted to ‘very violent thoughts’. Now, he believes in calm, patient, unemotional, non-violent preaching. This he credits to his parents and to the humane treatment he received. But each jihadi is different; there is no one single trajectory of disengagement. Many factors can go into disengagement beyond what Ahmed experienced, including disillusionment, new friendships, and changing priorities. Prison can be a force for radicalisation, but it can also offer the opportunity to reflect and take stock, and thus serve as a place for the process of disengagement to unfold, as it did for Ahmed.

Julie Chernov Hwang (jchwang@goucher.edu) is Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Relations at Goucher College.