Editor’s note: For Indonesia-watchers the activities of the military and its leaders remain largely opaque and perhaps even menacing. In recent years the steady stream of memoirs and biographies by and about military leaders has, in some cases, assuaged some of this mystery and in others, added to the intrigue. As the public and judicial gaze has increasingly turned to the actions of military leaders with connections to the New Order, the memoir has been engaged by some as a form of testimony in an effort to ‘clear their name’. Whatever the motivation, with each new addition to this genre, we are offered new insights into the fractious and often treacherous ‘interior’ world of the Indonesian Armed Forces.

Suparman holds the line but reveals some new insights into the transition of power after the fall of the New Order

Bob Lowry

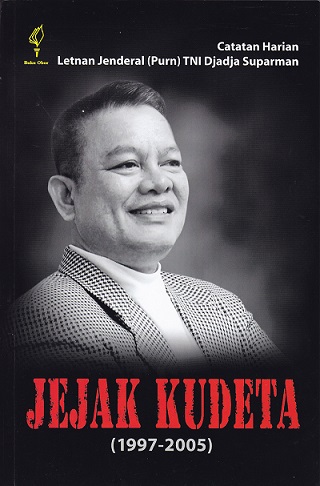

Djaja Suparman was one of the key military leaders who shepherded the transition to democracy in Indonesia. He was military commander (Pangdam) in East Java straddling the fall of Suharto and Pangdam Jakarta at the time of the first democratic parliamentary elections in June 1999. Like the majority of his military contemporaries he had an ideological commitment to the structures of Suharto’s New Order, if not to Suharto himself, but accepted that the military no longer had the legitimacy to impose its will.

However, it succeeded in containing the aspirations of the revolutionary alternative elites and protecting the interests of the military and the New Order elites in the democratic transition. The title of this book, Jejak Kudeta (1997-2005) (Uncovering the Coup D’etat (1997-2005) labelling Suharto’s ‘fall’ a coup d’etat, is indicative of a hangover from the New Order mindset.

Whatever your view of the outcome of the democratic transition, it is fair to say that Djaja was a very competent field commander. He succeeded in maintaining the cohesion and effectiveness of the troops under his command in highly stressful circumstances; maintaining cooperation with the other agencies with whom he had to collaborate, particularly the police; and influencing and containing the aspirations of those trying to topple the regime and take charge of the transition. It is also true that the transition to democracy in the area under Djaja’s command was relatively bloodless despite the mass mobilisations surrounding the Special Session of the Peoples Representative Assembly (SI MPR) in November 1998 and the elections for parliament and the president the following year.

Not naming names

This book is worth reading because of Djaja’s role in this pivotal chapter of Indonesia’s contemporary life, but a good editor would have improved the work immeasurably. It is didactic, repetitious, jumps confusingly between the first and third person and most frustratingly of all, does not name names. For a work of ‘history’ supposedly based on a diary covering the period, the absence of names greatly discounts the value of the book. His rationale for this approach is that he does not want to denigrate others or to defend himself, but to focus on the lessons for leaders and for leadership in all its dynamics. Readers can hardly do that if they are not provided with enough of the story to draw their own conclusions.

If some of the peripheral characters had not been named this deficiency could have been overlooked but he fails to name many of the central characters, the most prominent of who was named ‘The Source’, or ‘Sumber’ in Indonesian, who could aptly be named an ‘Oracle’. Between August 1997 and April 1998 this Oracle supposedly laid out the course of events that led to the fall of Suharto and the transition to democracy. He also suggested how Djaja should respond to the unfolding events and Djaja affirms that all his predictions and the consequences for Djaja unfolded just as the Oracle had forecast.

Being Superman

When Djaja was in senior high school he saw the need for a second name and adopted it from his comic book hero Superman. He certainly portrays himself in this light as the defender of life and liberty and the Constitution, but who was the Oracle? Was he merely an invention of Djaja’s imagination, an alter ego or post-facto invention? The only clue we are given is that the Oracle was broadly knowledgeable about domestic and international political developments. The presence of an Oracle also suggests the presence of an evil genius mastermind behind all the machinations. But despite his best efforts Djaja was not able to identify him and there was no suggestion that they were one and the same.

Djaja tells us that the Oracle claimed that there was a small shadowy group (Kelompok Perubahan Abu-abu) working for change within the military, allied to Abdurrahman Wahid (Gus Dur) the leader of Nahdlatul Ulama. They had a masterplan to topple the New Order, establish a presidium, impose a new constitution and sack the senior military leadership to clear the way for radical military reform. The evidence he gives for this was the alleged involvement of some junior military officers in the demonstrations leading to the resignation of Suharto and Gus Dur’s foiled attempt to promote Agus Wirahadikusuma, the leader of the radical reform group, to lead the army. There is some truth in this but it is only a small part of the story of the toppling of Suharto and the transition to democracy.

Likewise there are numerous references to foreign influences without any attempt to define them or evaluate how significant they were to the outcome of events. According to Djaja’s account, these foreign forces were out to topple the New Order through the activities of international and domestic non-government organisations. They also planned to separate East Timor and Papua from Indonesia and constrain the defence budget to weaken the military’s capacity to respond. Again the aim was to impose a ‘Presidium’ to lead Indonesia to its first democratic elections. Such references serve to excuse the failures of the New Order and its beneficiaries and to diminish the legitimacy of domestic opponents of the regime.

The last mysterious group Djaja points to as responsible for the mayhem, were the ‘provocateurs’ who were ordered to conduct demonstrations by ‘someone’, working inwards from provincial centres to the capital. Accordingly, demonstrations were not spontaneous. This is proven, he tells us, by the fact that the press often knew where the action was to occur before the security forces. However, Djaja assures the reader that although the ‘provocateurs’ often had a military bearing, they were not and had not been members of the military. The inference is that they were chosen because of their appearance to incriminate the military and spread dissension within the military and between the military and police.

A report in Time magazine prior to the fall of Suharto alleged that Djaja was supporting the demonstrations, which resulted in him being called to Jakarta by a ‘very influential person’ to explain his actions. In his book, Djaja tells us that there were forces outside East Java controlling and financing political mobilisation in East Java but again, there is no direct reference to who they were.

The transition

Djaja’s success in minimising the casualties and damage wrought by the anti-Suharto forces in East Java in the wake of the student demonstrations and violence in mid-May 1998 saw TNI Commander General Wiranto give him the leadership of the Jakarta military district, the most important operational command in the country. Djaja took over from Major General Sjafrie Sjamsoeddin who was seen to have failed to respond adequately to the violence leading to the fall of Suharto. The climax of the battle between the forces of the New Order elites surrounding Habibie and those advocating the imposition of a ‘Presidium’ came with the Special Session of the People’s Consultative (SI MPR) assembly in November 1998.

In the lead up to the session, Djaja established strong links with the police who now had prime responsibility for internal security. He spoke to all groups likely to be involved and attempted to establish the ground rules that would allow peaceful demonstrations and avoid casualties and damage. Conversely, the anti-Habibie forces tried to co-opt Djaja to allow demonstrators into the parliamentary complex to force the parliament to establish the Presidium, presumably to be led by Amien Rais or Gus Dur or both. Despite enormous pressure, the security forces held their ground allowing Habibie and the MPR to set the reform agenda leading to elections in 1999.

In all these contests Djaja portrays himself as being above politics, the defender of the Constitution and the people, above the sectoral and personal interests of the anti-Suharto and anti-Habibie forces. There is no acknowledgement that by choosing that course, whether right or wrong, he was actually supporting a particular side. He acknowledges that the military and police were squeezed between the two contestants, but insists that such problems must be resolved politically in accordance with the authorised mechanisms. This, of course, assumes that the authorised mechanisms are considered legitimate by all parties.

Djaja was rewarded for his service and promoted to Commander of the Army Strategic Reserve (Kostrad) in November 1999. Under normal circumstances he could have expected to be a leading contender for the army leadership thereafter. However, after only three months in Kostrad he was shunted aside by Gus Dur in his bid to have Agus Wirahadikusuma fast tracked to the leadership of the army. Despite his disappointment, Djaja continued in other roles, as Commandant of the TNI Command and Staff College and Inspector General of the TNI, before retiring on 1 January 2006.

It is clear that in writing this book, part of Djaja’s intention is to clear his name of numerous accusations of alleged misconduct. Amongst other things, Djaja was accused of embezzling money from land deals in East Java and using $US14 million of Kostrad business funds to finance Laskar Jihad operations in Ambon. He has also been accused of involvement in the Trisakti and Semanggi killings and the Bali bombing. According to Djaja, such claims were part of a campaign of character assassination forecast by the Oracle. Some of these accusations are patently false and others he refuted.

Whether his refutations are accepted or not, his call for some form of genuinely impartial inquiry that would examine all aspects of the first years of the transition to democracy should be supported.

Bob Lowry (robertwlowry@bigpond.com) is an observer of Indonesian defence and security affairs and politics.