Dave McRae

Indonesia's National Narcotics Board advocates the death penalty for narcotics crimes, Dave McRae

Surveying the death penalty in 2008for Inside Indonesia, I concluded that there was little prospect that Indonesia would abolish capital punishment. Executions had peaked in 2008, with ten in a single year – almost half the total number conducted since the fall of Suharto. Imminent elections also seemed to suggest more of Indonesia's 100-odd death row prisoners could soon be brought before firing squads. Meanwhile, the Constitutional Court had eschewed two chances to repeal death penalty statutes, finding neither the death penalty for narcotics crimes nor firing squads as a method of execution to violate the constitution's bill of rights.

Since then, however, Indonesia's stance on capital punishment has shifted. After the 2008 peak, Indonesia has conducted no executions at all. Courts have also started to hand down fewer death sentences, with the decrease clearest for narcotics-related crimes. Most significantly, Indonesian president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono decided to grant clemency to four people on death row for narcotic offences in 2011 and 2012, reducing their sentences to life imprisonment. These decisions constitute a clear departure from previous government policy and rhetoric. Beforehand, there had been only one known case of clemency for a capital offence in the past 30 years.

What is driving these changes, and are they the first steps along the path to abolition? Unexpectedly, it has been the execution of an Indonesian overseas that has newly energised Indonesia's abolitionists.

Momentum for abolition

Indonesia has always had a small but committed abolitionist movement. But they have struggled to make headway in the face of majority public support for the death penalty, reinforced by vocal conservatives. Over the past 18 months, though, the Indonesian government has advocated strenuously for Indonesians facing execution overseas, whatever their crime may be. The contrast between blanket representations for clemency abroad and continued application of the death penalty at home has become increasingly hard to ignore. The imperative to protect Indonesian citizens abroad has also allowed abolitionists to make a pragmatic case to end capital punishment.

But although this issue has done the most to shift Indonesia's position, it is not the only factor. The death penalty also impedes Indonesia's cooperation with other countries around extradition and the recovery of assets, to the frustration of some law enforcement officials, including Indonesia's deputy attorney general for special crimes. Civil servants responsible for carrying out executions have also expressed their distaste for the task. Prosecutors from the Attorney General's department administer executions, from informing the condemned prisoner three days prior to their execution, to receiving any last requests or statements, giving the order to the police firing squad to commence the execution, and observing the prisoner's body to confirm death. A prosecutor, speaking in a personal capacity, indicated that several officials within the department would prefer that no executions happen during their term. Notably, Attorney General Basrief Arief also reportedly recommended that the president grant clemency to Meirika Franola, who was on death row for a narcotics offence.

More speculatively, President Yudhoyono may see steering Indonesia towards abolition as a chance to boost Indonesia's international human rights reputation deep into his second and final presidential term. Some Indonesian activists perceive that Yudhoyono's support for the death penalty was one reason he was overlooked for the 2008 Nobel Peace Prize for the Aceh peace process. There is speculation that Yudhoyono aspires to the post of UN Secretary General in 2016: a reputation for frequent executions would count against him there, too.

None of these factors though lend impetus to abolition to the same degree as the government's obligation to protect Indonesians facing the death penalty abroad. This has been a searing foreign policy hot potato for the Indonesian government, ever since the execution of Indonesian domestic worker Ruyati binti Satubi in Saudi Arabia in mid-2011. Executed for stabbing her employer to death, Ruyati's case generated an uproar in Indonesia, where it is recognised that such murders are often the consequence of maltreatment of Indonesian maids by foreign employers. Many Indonesians felt that the government had done little to assist Ruyati. The resultant outcry has put intense pressure on the government to prevent any further executions.

Reconciling foreign and domestic policy

Soon after Ruyati's case, the government established a taskforce of officials and private citizens to establish protections for Indonesian citizens facing the death penalty abroad. The taskforce pursued diplomatic measures, such as President Yudhoyono writing personally in support of clemency, as well as legal approaches, including the establishment of a network of lawyers on retainer in priority countries. The government also took the extraordinary step of paying blood money to free several Indonesians facing execution for murder in Saudi Arabia. The taskforce was disbanded after a year, but this intensive diplomacy has continued. The government is presently negotiating a blood money payment for another domestic worker in Saudi Arabia, for example. In all, the government claims to have helped 110 Indonesians avoid the death penalty abroad, including securing the release of 33 individuals to return to Indonesia.

The Indonesian government has also turned to this foreign advocacy each time it has come under fire for granting clemency to narcotics prisoners within Indonesia. This has proven to be a potent argument. In one example, government death penalty taskforce spokesperson Humphrey R. Djemat suggested on a television talk show that if people wanted to criticise the government as soft on drugs for granting clemency to Australian narcotics convict Schapelle Corby, they should also have criticised the government when it gained clemency for Indonesian drug convicts overseas. The camera then panned straight to prominent government critic Yusril Ihza Mahendra, showing him sullen-faced with his eyes fixed firmly on the table in front of him.

When critics subsequently attacked the government over the death penalty clemency decisions, Indonesian Foreign Minister Marty Natalegawa waded into the debate, again drawing explicit links between foreign advocacy and domestic policy. Natalegawa reminded Indonesians that 42 of the 100 Indonesians to escape the death penalty abroad at that point had faced narcotics charges. 'So, if we discuss narcotics crimes and the granting of clemency domestically,' Republika Online reported Natalegawa saying, 'we also must remember that overseas 45 per cent of Indonesians are facing the death penalty [for narcotics crimes].' In the same press conference, Natalegawa also reportedly cited an international trend toward abolition, saying 'Indonesia itself is already headed in that direction.'

Significant opposition remains

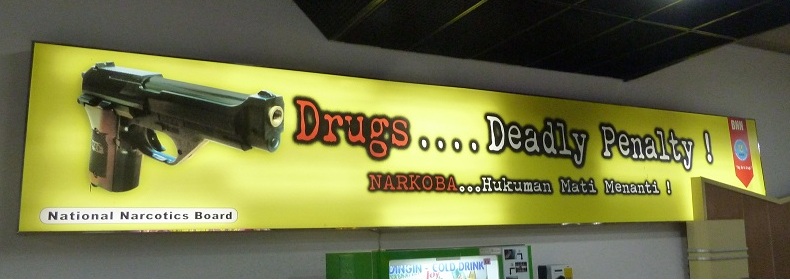

President Yudhoyono's decision to grant clemency to four narcotics prisoners has been the strongest public indication to date of a shift in the Indonesian government's position on the death penalty. Predictably, given that polling suggests strong public support for its continuation, the decision has been controversial. Public figures lined up to criticise the clemency decisions, from politicians, to the Constitutional Court chief justice, as well as religious leaders. The strongest reaction though came from the National Narcotics Board, universally known by its acronym BNN. The agency has long advocated stern penalties for narcotics crimes. General Gories Mere, BNN head from 2009 until his retirement in December 2012, repeatedly drew attention to the availability of the death penalty for possession of as little as five grams of drugs, and criticised the courts for not handing down the death penalty more often. His statements seemed to gain little traction, though, until the clemency decisions gave BNN its chance to act.

One of the narcotics prisoners to receive clemency was Meirika Franola, originally sentenced to death in 2000. Shortly after her clemency decision became public, (more than a year after Yudhoyono had handed down the decision), BNN arrested Franola at the Tangerang women's prison. BNN depicted Franola as a high-level player in a drug syndicate spanning several prisons, led by Nigerian Hillary Chimezie. The arrests were a major embarrassment to the government, spurring accusations of carelessness and naivety, and even that drug syndicates had infiltrated the president's ring of advisors.

Franola's arrest led to calls to revoke her clemency and reimpose the death penalty, an extraordinary extrajudicial step that the government nevertheless initially appeared to consider. BNN claimed that the arrest was not politically motivated; that her name had merely cropped up by chance during the investigation of an Indonesian drug courier arrested in Bandung. However the case came to their attention, BNN clearly utilised this case as a way to drive forward their broader political agenda.

Whither the death penalty

Four years without an execution, the clemency decisions, Natalegawa's statement and the ongoing pressure to protect citizens abroad are all cause for more optimism now than in recent times that Indonesia will end capital punishment. Belying these positive signs of a move towards abolition, the courts handed down at least 11 death sentences in 2012, bringing the total number of prisoners on death row to 133 people by Attorney-General's Department figures, with at least one further death sentence since. Of particular concern, the Indonesian Attorney-General also announced that eight prisoners were to be executed, with the Deputy Attorney-General for General Crimes saying executions must take place in 2013.

Such announcements have come and gone before without leading to executions, and may do so again this time. But for the moment at least, Indonesia remains a country that opposes the death penalty for its own citizens abroad but continues to apply capital punishment within its own borders.

Dave McRae (dmcrae@lowyinstitute.org) is a research fellow in the East Asia Program at the Lowy Institute for International Policy and a member of the Inside Indonesia editorial committee. His report A Key Domino: Indonesia's Death Penalty Politics is available for download.