Rachel Rinaldo

One of the peculiar characteristics of Indonesia for Western scholars is the persistence of misconceptions about the country’s gender relations. Certainly, Southeast Asia has aromanticised reputation for gender fluidity. But more important may be the legacy of mid-twentieth century social scientists who saw Indonesian women’s work outside the house as a sign of equality and high status. At least in the United States, this has become an oddly common presumption about Indonesia, despite much scholarship that suggests that women’s mobility in public spaces and ability to earn income cannot necessarily be equated with power.

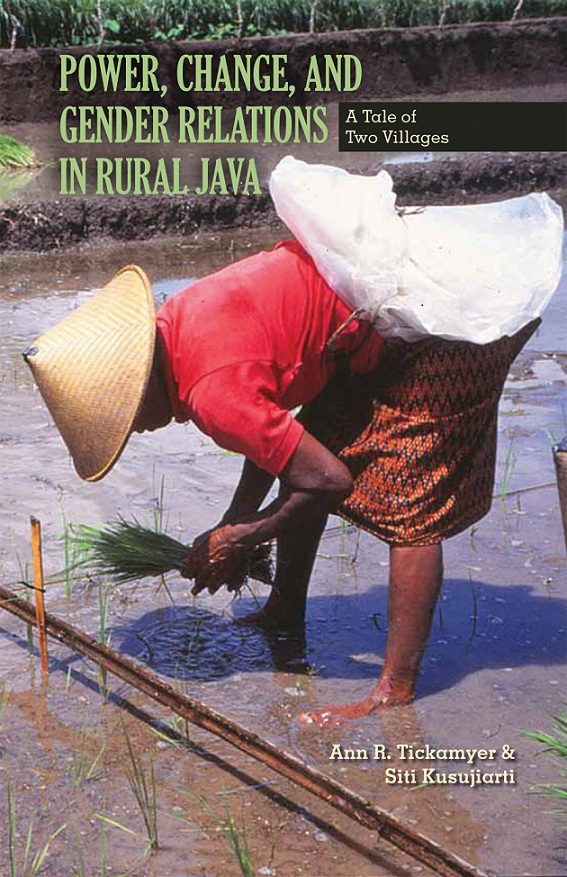

Ann Tickamyer and Siti Kusujiarti’s Power, Change, and Gender Relations in Rural Java hews to this latter tradition, challenging romanticised stereotypes, while also digging deep into the fundamental paradoxes of gender in Java. Tickamyer is an American sociologist, while Kusujiarti, also a sociologist, is Indonesian but teaches in the US. Together they provide a captivating insider/outsider perspective on everyday life and social change in two Central Javanese villages. Based on quantitative and qualitative fieldwork from the mid-1990s up till 2010, their book should become the essential source for understanding gender in rural Java.

Tickamyer and Kusujiari maintain that there is no simple answer to the question of women’s status in rural Java – it is contradictory through and through. Women indeed have access to economic resources, and are often important income earners for their households, something which is thought by many social scientists to be correlated with power. On the other hand, women face significant ‘structural and cultural obstacles to becoming effective leaders and to gaining access to significant roles in the society’. In this, they build on the work of earlier Indonesia scholars, such as Norma Sullivan, who observed that middle class women in Java act as household managers but never as masters. Tickamyer and Kusujiarti argue that scholars need to examine multiple facets of women’s lives in order to really see the disjunction between economic autonomy and actual status. They systematically investigate several major aspects of gender and power in village life. They look at the level of individual gender ideology, as well as the division of labor in and outside the household, and also scrutinize involvement in village social activities, particularly state-controlled welfare organisations. Moreover, because they studied one village in the Sleman district that was poorer and more rural, and one village in Bantul district that was more affluent and becoming urbanised, they also have some surprising conclusions about the role of class in gender relations.

The findings are striking. Like many Javanese, most of the villagers in the study adhere to a binary concept of gender difference that emphasises spiritual differences between men and women. But while the villagers emphasise complementarity, saying that men and women have different but equally valuable roles, Tickamyer and Kusujiari find that complementarity does not mean parity. Women can participate in most activities, but men are considered to be more spiritually powerful. Women are defined primarily as mothers and wives, and men’s and women’s roles are valued differently. Men are not expected to take part in domestic tasks, as this is not seen as their natural domain. They have time to be involved in the civic and public activities that are closely associated with status and power, while women must grapple with household responsibilities before they can take on other tasks. Villagers rarely question this arrangement. Even more so than men, women embrace traditionalist gender ideology, even when it is at odds with the reality of their lives. Indeed, Tickamyer and Kusujiarti observe that women profess their equality and subordination simultaneously.

A history of inequality

Why aren’t villagers more critical of the contradictions in gender? Tickamyer and Kusujiarti say that this gender ideology has a long history in Java, and that there is also a uniquely Javanese approach to power that embraces and seeks to harmonise contradiction. More importantly, perhaps, the Indonesian state has had a role in promulgating such ideas. As scholars like Julia Suryakusuma have shown, the Suharto regime co-opted Javanese cultural concepts, including gender ideology and indoctrinated them through its social programs.

Tickamyer and Kusujiarti suggest that women are committed to traditionalist gender ideology because they have been more exposed to it through the state-sponsored welfare organisations, such as the PKK (Pemberdayaan Kesejahteraan Keluarga – Family Welfare Movement) that are directed at women. A potentially positive development is that in the post-New Order era, PKK has had to reinvent itself and it has recently incorporated a more women’s rights friendly agenda.

Certainly, there is often a gap between what people say and what they do. Most women in the villages are indeed doing some kind of work to earn income, usually in agriculture or trade. In some cases, they out-earn their husbands. Nonetheless, women are uncomfortable with having a dominant role in the household. Bu Margini’s poignant observations reflect common sentiments among village women: ‘I don’t know how I feel about my husband. I earn much more money than he does, and he always agrees to whatever I say. He does whatever I want….But I don’t feel that I win over him; I still perceive that he is the head of our family.’ As Tickamyer and Kusujiarti note, income and employment are not sufficient to change women’s status in the household or in public life.

The gendered division of labour in the household has changed very little since the mid-1990s, and the increased urbanisation of one village does not turn out to make much of a difference. While men claimed to be willing to help with household tasks, Tickamyer and Kusujiarti found that husbands performed just 4 per cent of household chores in the more rural Sleman, and 6.5 per cent in the more urbanised Bantul. ‘No husband or son is involved in food preparation, buying groceries, or going to the market, while the wives’ participation in these tasks is very high’, they maintain. When women are employed, paid helpers, daughters, and extended family contribute to household chores. As the sociologist Arlie Hochschild famously commented in The Second Shift, her examination of American family life in the 1980s, women’s lives have changed, but men’s have not.

The era of democratisation ushered in since 1998 should have provided new opportunities for village women in public life. Women’s rights activists were at last unleashed, freedom of expression became a reality, gender and sexuality seemed to be more contested, and NGOs have popped up throughout the country. Nevertheless, the traditionalist gender ideology maintains a strong hold, and it is still uncommon for Indonesian women to hold office. Tickamyer and Kusujiarti find that women occasionally become sub-village heads, but such leaders continue to assert the importance of conventional gender arrangements. Meanwhile, Bu Midiwati becomes a rare example of a female bupati (district head), yet she is apparently a stand-in for her husband. Democratic reform indeed opened up exciting new possibilities for women in Indonesia, but as Tickamyer and Kusujiarti rightly observe, women’s public activities are always constrained by the expectation that the domestic sphere is their primary responsibility. As feminists have long known, private and public life are intimately linked.

Contradictions amid change

Power, Change, and Gender Relations in Rural Java captures the texture of gender relations in these two villages with a critical feminist eye. Yet it also raises vital questions for those who are concerned about women’s rights and egalitarian social change. The strong similarities between the Sleman and the Bantul village suggest that economic development and urbanisation has not brought significant empowerment for village women. A gender ideology that marginalises women from power persists despite social changes that might seem to challenge it. The assumption that economic development automatically empowers women is widespread, despite years of more nuanced research by scholars like Tickamyer and Kusujiarti. They show why we must delve deep to understand how development and urbanisation bring change or reproduce various aspects of life.

Democratisation has also often been seen as a panacea for gender inequality. Certainly, in the years since 1998, Indonesia has developed a lively women’s movement, with especially vibrant activism on the part of Muslim women’s organisations, migrant worker advocates and groups working to build religious and ethnic tolerance among women. Such activism is essential and consequential, but often it is small-scale, does not reach rural areas, or does not really contest the gendered status quo. Based on my own research among urban women’s rights activists, I think gender norms in Indonesia are indeed shifting, but the changes are mostly among the urban middle classes. Power, Change, and Gender Relations is a powerful reminder that women’s access to economic resources does not necessarily bring status or power and that changes in gender norms come slowly, and sometimes not at all.

Ann R. Tickamyer and Siti Kusujiarti, Power, Change, and Gender Relations in Rural Java: A Tale of Two Villages, Ohio University Press, 2012.

Rachel Rinaldo (rar8y@virginia.edu) is assistant professor of sociology at the University of Virginia.