Social media campaigns highlight the need for criminal law reform in Indonesia

Arjuna Dibley

The day after Indonesia’s last presidential election campaign started on 3 June 2009, the then-presidential candidate Megawati Sukarnoputri and her running-mate Prabowo Subianto made a surprise stop-over in the town of Tangerang in West Java. They visited Prita Mulyasari, a young mother defending two charges of criminal defamation. Shortly afterwards the then-Vice President Jusuf Kalla, General Wiranto and President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono – who is ordinarily non-interventionist when it comes to discussions of legal affairs – all made public statements about the unjust use of criminal defamation in the Mulyasari case.

This unprecedented level of political condemnation, media scrutiny and public debate about criminal defamation laws came about, in part, because of an effective social media campaign surrounding the Mulyasari case. Activists used social media to successfully raise the profile of problems with Indonesia’s criminal law. But while social media was effectively used to draw attention to these issues, it has not been a panacea for achieving long lasting legal reform.

A problematic Criminal Code

Mulyasari’s case started from an email she sent to a group of around twenty friends and work colleagues in 2008, complaining about her treatment at a private hospital in Tangerang. In her email, Mulyasari claimed that she was misdiagnosed and that the hospital had given her unnecessary treatment to increase her medical bill. Mulyasari also wrote that when she complained about her treatment to the hospital management, she was treated poorly. Over the following months Mulyasari's private email went ‘viral’ over the Internet, circulating widely on blogs and news websites and was even published in full on the popular news web-site detik.com.

In early 2009, the email came to the attention of Mulyasari’s treating doctors. In addition to filing a civil defamation law suit against her, the doctors also reported her to the Tangerang police for criminal defamation. In April 2009 Mulyasari was indicted for two criminal defamation charges by prosecutors at the Banten Prosecutors Office. Mulyasari should have been brought before a judge within 24 hours of her arrest. Instead, the prosecutors incorrectly used their powers under Indonesia’s Code of Criminal Procedure to place her in pre-trial detention for 21 days.

Ten years after Indonesia’s process of political reformation, Mulyasari’s situation attracted public attention because it highlighted ongoing weaknesses within Indonesia’s democracy. After the fall of Suharto, the Indonesian Constitution of 1945 was amended to protect citizens’ right to freedom of expression. But the Mulyasari case demonstrated that there were many legal hurdles to overcome before this right could be realised in practice, including the outdated Criminal Code.

Indonesia’s Criminal Code (adopted from the Dutch code during the era of colonial rule) imposes a jail term and/or a fine upon any person who intentionally makes a statement which contains insults or untruths which injure the reputation of the person or institution at which they are aimed. Owing to a new and controversial 2009 law, criminal defamation offences in relation to statements made on the internet or through electronic transactions have been strengthened. These new electronic based defamation offences are punishable by a maximum fine of Rp.1 billion (A$123 000), as well as a maximum of six years imprisonment. Mulyasari was charged with both the old and new criminal defamation laws.

Coin for Prita

Mulyasari's case lasted a long time because it was appealed on numerous occasions by the prosecution. The first of the trials against Mulyasari occurred in June 2009 at the Tangerang State Court, where the presiding judge dismissed the criminal charges against her on the basis that the prosec{jcomments on}ution case had not been proved. Following an appeal of the June decision by the Banten prosecutors, the State Court reheard Mulyasari’s case in September 2009 and acquitted her of both defamation charges. The acquittal was hailed as a victory by pro-freedom of expression activists who had made creative use of social media tools to support Mulyasari.

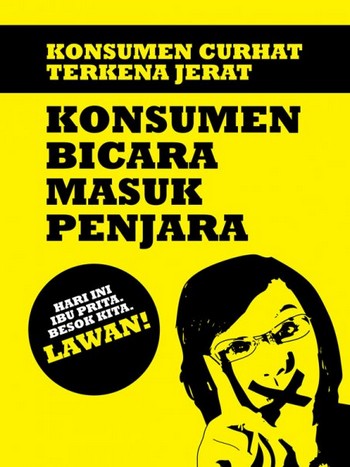

The images of Mulyasari, a young middle-class Muslim mother, in detention for an email she wrote to friends, caused a public stir in Indonesia. As a consequence, during her period of pre-trial detention a campaign using new social media emerged in support of her. The campaign, called Coin for Prita (Koin Peduli Prita), mainly operated through Facebook.

The purpose of the campaign was to raise awareness of Mulyasari’s plight and to encourage people to donate coins to help her pay any civil damages and the criminal fines. In this sense, it was a rapid and major success. The online campaign received widespread press coverage in Indonesia and across the world and by November 2009 its dedicated Facebook page had almost 400,000 supporters and was complemented with offline events including a fundraising concert. The concert, held at the Hard Rock Café in Jakarta, attracted high profile Indonesian politicians, business people and musicians, including a performance by pop sensation Nidji who wrote a song especially for the event.

By December 2009 the organisers of the Coin For Prita campaign had stopped collecting money after raising over Rp.800 million (A$98,584), comprising five truckloads of coins. The coins were ultimately converted into a cheque which was presented to Mulyasari, who used some of the funds to pay for her legal costs.

Limits of the social media ‘conversation’

|

|

A photo distributed via Twitter calling volunteers to help count coins collected as part of the Coin for Prita campaign / Enda Nasution |

The Coin For Prita campaign successfully generated broad condemnation of the use of criminal defamation laws by senior political figures in Indonesia. The case also prompted a flurry of debate and discussion about how criminal defamation laws should be balanced against free speech rights in Indonesia. On one side of the debate were free speech activists calling for the abolition of the laws because they infringed Indonesian citizens’ constitutional right to freedom of expression. On the other side of the debate were a few government ministers and legal academics who argued that the laws were needed to protect the reputation of government, businesses and individuals. This debate played out in public interest litigation in the Constitutional Court, the opinion pages of major newspapers, blogs and in legal academic and policy forums. The Mulyasari case featured heavily in these debates.

However, the social media campaign, and the public debate which followed, has not resulted in reform to criminal defamation laws. Despite the fact that criminal defamation laws were so robustly opposed at the height of the Mulyasari case by major political figures, the laws (both the Criminal Code offence and the new 2009 offence) remain largely unreformed. In fact, they continue to be used to charge bloggers and other internet users in Indonesia. For example in March 2010, Muhammad Wahyu – a university student from East Java – was charged with two criminal defamation offences, after he made disparaging comments on the personal Facebook page of a fellow female student. Wahyu was given a three month jail term, suspended for six months.

Additionally, the campaign built around Mulyasari’s case ultimately did little to redress her own situation. After the initial hype surrounding the Mulyasari case died down, her case was again appealed by the Banten prosecutors in July 2011. Over a year after her last trial, the social media ‘conversation’ around Mulyasari had moved on to other issues, and consequently her Supreme Court appeal was not met with any of the social media fanfare which had surrounded her initial indictment. In what was a remarkably underreported event, the Indonesian Supreme Court convicted Mulyasari and handed down a six month suspended sentence.

Mulyasari’s experience shows that new social media can rapidly bring issues of injustice to the public’s attention through small simple messages and images. A large number of Indonesians use social media allowing these messages to rapidly go ‘viral’ across the internet and quickly generate political pressure. However, social media activism to date in Indonesia, so focused on short messages and rapid responses to new cases, often lacks the longevity and depth required to instigate systemic legal reforms. As Mulyasari’s case shows, once the initial hype over a particular case looses currency, and the social media ‘conversation’ moves on, the difficult, complex and longer term goal of creating law reform remains unresolved.

Arjuna Dibley (arjuna.dibley@gmail.com) is a Sydney based lawyer who wrote a thesis about criminal defamation and democracy in Indonesia, including the Mulyasari case, in 2010. He regularly writes about Indonesia on public policy blogs and in the press.