Mosques provide more than just spiritual salvation during the fasting month

Ahmad Muhajir

No sleeping in the mosqueAhmad Muhajir |

Most days, after the congregation of Az-Zawiyah mosque in southern Jakarta finish their noon prayer, there is a familiar scene. Most of the worshippers, who work in nearby construction sites, rush to food stalls to appease their hunger. Only a small number of people sit devotedly for any length of time, concentrating on their devotions.

During the Islamic fasting month, the situation is different. Almost all participants in the prayer session stay on for a while, spending some time on a worldly pleasure in the house of God: taking a nap. This practice is observable in many prayer houses during the holy month of Ramadan, when Muslims are taught to resist worldly temptations. But the fact that it is tolerated reveals religious leniency and, to some extent, sympathy for fasting Muslims.

Ramadan and new habits

The daily life of the average Indonesian Muslim changes several ways during the fasting month. Sleeping hours are modified to accommodate an early breakfast (sahur) at a time when people are usually in deep sleep before dawn. Muslims consume no foods or drinks throughout the day until sunset, although one can still find discreet food stalls and restaurants which continue to serve customers. Additional night prayers, special for Ramadan, the tarawih, are observed in congregation, increasing attendance at mosques but reducing the resting time of Muslims.

People’s exposure to religious teachings also intensifies because there are all but constant Islamic sermons available in both prayer houses and the media. One consequence is that during the month people make more donations to religious causes and ritual observation generally rises. Despite such changes, people still work as usual and the wheels of the economy do not slow down.

During Ramadan, when working Muslims still have their lunch breaks but do not eat because they fast, many go to prayer houses. This reflects the increased piety of the month. But it also has a more prosaic explanation: people need to find a place to use their break time wisely. It is not surprising therefore that the scene inside mosques changes rather dramatically following the end of daytime prayer sessions, from one with people bowing, touching their foreheads to the floor in prayer, to one with people lying on their backs deep in slumber. This activity is popular especially among men.

Most working Muslim women do not share the habit of taking naps in mosques. Only very few of them stay on to sleep in the area reserved for female worshippers, indicated by a partition. The partitions are commonly made of fabric or board, and serve as a wall that blocks visibility from the other side. Hidden behind such walls are the women who take the opportunity to lie down for a rest after prayers. But many women simply feel that the partitions are not large enough, or too flimsy, to give them the comfort and privacy they need to be able to sleep. And because the space provided for female worshippers is typically much smaller than that for males, women feel that they have to give way for women who are coming in to pray, rather than taking up space by sleeping.

Relaxing in prayer houses

For men, however, prayer houses have long served in Indonesian Islam not only as the places of worship but also as places for taking a rest. They are typically spacious and their floors are regularly cleaned. The temperature in mosques and other prayer houses is also usually pleasant, thanks to the high ceilings and the natural or mechanical wind that blows from outside or from fans and air conditioners. Add thick carpets, and they offer a free and comfortable space to lie down and relax for a short while after prayers.

In the small mosque of Az-Zawiyah around three dozen workers would took a nap of 30 minutes to an hour during their lunch break on Ramadan days. In the national Islamic prayer house, the Grand Mosque of Istiqlal, hundreds of visitors would lie down on the carpeted floor in the afternoon while waiting to break their fast.

Likewise, travellers who are heading back to their hometowns as they take part in the great annual migration that occurs toward the end of Ramadan every year in Indonesia, particularly those in private vehicles, find big mosques good stopping places along the way. The great mosque in Tapin district in South Kalimantan, for instance, experiences a tremendous flow of visitors as people stop by on their trips to and from Banjarmasin. A security officer in Al-Azhar mosque in Bekasi, West Java says that the number of travellers who transit in his workplace might top one thousand every day during the migration (mudik) period.

Such visitors typically use the mosque restrooms and then take ablutions, do their prayers and afterwards, close their sleepy eyes for a few minutes. After all, having some rest en route is highly recommended to reduce the risk of motor vehicle accidents. While adults do such things, the small children travelling with them can have fun by running in and around the mosque and enjoying some fresh air before they continue on the long journey to ‘grandpa’s house’. Mosques in this way supplement the petrol stations and restaurants people also stop off at while travelling home for the Id al-Fitr holiday.

Prohibited or permitted?

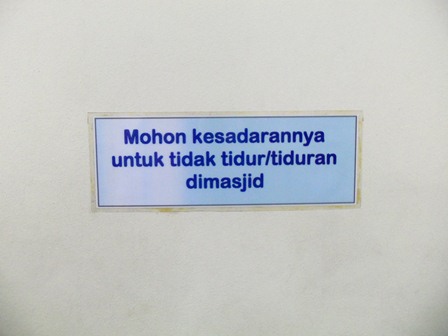

Not all mosque managers are happy, however, to see people taking a nap. One can often find notes on the wall, the front door or even the pillars of some prayer houses that prohibit the act of sleeping. There are also often instructions to silence cell phones, something that people are more likely to comply with. Some notes are more recommendatory than prohibitive in nature, along the lines of ‘this place should not function as a sleeping room’. Sometimes, though not that commonly, there are even staff who bother to wake up those taking a nap.

More often than not, people ignore such notes and the habit of nap taking in mosques persists, especially during Ramadan. Apparently, there is a basis in Islamic law and tradition for this. In Islamic legal discourse, sleeping in mosques is generally viewed as a permissible act. According to sound hadith (sayings and deeds of the Prophet) some of the first generation of Muslims did it, and more prominently, so did members of a group that was embryonic to the later Sufi community There was a group of people in early Muslim history called ‘ahlus suffah’ who slept in mosques, wore rough clothing and lived humble lives. Later on, this group arguably inspired the ideas of tasawwuf (Sufism) and people who follow their way of life formed the Sufi community.

On the other hand, it is true that some classical scholars did not favor this position and argued instead that sleeping in mosques was a reprehensible act. However, given the hadith and the absence of any explicit prohibition by the Prophet, the legal opinion permitting the act receives wider acceptance. Only in two exceptional circumstances does the law clearly forbid sleeping in mosques. The first is when doing so makes the prayer house dirty, and the second is when the prohibition comes from a person who owns the mosque privately.

Religious leniency

Ramadan is a month when the value of every good deed is multiplied. Islamic preachers urge their fellow Muslims to maximise the efforts to perform their devotions, more so than in other months, and to have religious experiences beyond mere thirst and hunger. Learning to control one’s desires is often cited as being the core lesson to be attained from fasting, and seen from this perspective, taking a nap during the day in Ramadan may seem inappropriate: sleeping, after all, is worldly and inactive.

Viewed in another light, however, during Ramadan even sleeping might be counted as an act that earns religious reward. In an environment where the day is hot and the throat has dried up, when pious Muslims try to avoid the temptation of breaking their fast early – especially if they have witnessed others doing so – mosques provide shelter. Having a nap can help keep you on the straight and narrow. It seem that the keepers of many Indonesian mosques understand this. Accordingly, they leave the sleepers alone in their struggle to survive another day of Ramadan.

Ahmad Muhajir (ajir_82@yahoo.com) teaches at IAIN Antasari Banjarmasin and was a fellow in Indonesian Young Leaders program.