Julia Suryakusuma

In authoritarian contexts, the state seeks to control its subjects and deploy them to support regime goals. Indonesia’s New Order, often labelled an ‘authoritarian developmentalist’ regime, prioritised economic development. Politics was therefore seen as a risk to national stability, which the regime saw as a prerequisite for that development. Making up half of the population, women – including poor women – were depoliticised and mobilised to support the New Order’s developmentalist goals through a series of highly interventionist state institutions.

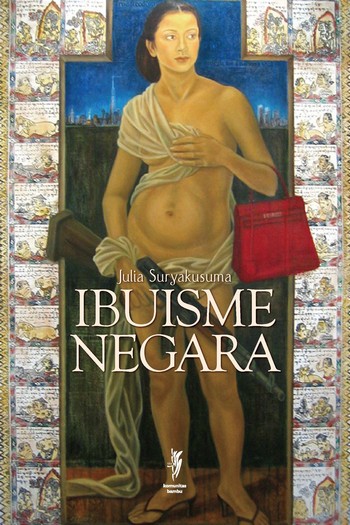

Under Suharto’s New Order, a corrupt and oppressive state therefore came to dominate all aspects of life – including the social construction of womanhood. In 1988, I wrote an MA thesis about this, called ‘State Ibuism: the Social Construction of Womanhood in New Order Indonesia’. The first gendered analysis of the New Order, the thesis was an attempt to look at the inappropriateness for poor village women of state-engineered programs imbued with middle-class values. In it, I argued that while women were not taken into account in formal politics, the social and political engineering of women was, in fact, an integral part of the New Order State’s stranglehold on Indonesian society. The dominant gender ideology defined women as wives and mothers, as epitomised in Dharma Wanita, the state-sanctioned organisation for civil servants’ wives. In the formal hierarchy of this nation-wide institution, the positions held by women paralleled those held by their husbands.

State Ibuism and was finally published in September 2011 as a bilingual book, in both the original English and an Indonesian translation. But why bother publishing it at all now? Haven’t we come a long way from the days of Suharto’s New Order? How is State Ibuism still relevant to present day Indonesia?

Public discourse and institutions in Indonesia have shifted significantly since I wrote State Ibuism almost a quarter of a century ago. But don’t be fooled. The mechanisms and outcomes of governmental control are still strikingly similar. ‘Gender’ is still essentially a mobilising force for programmatic intervention and social control (or neglect, as in the case of migrant domestic workers). Despite everything that has happened, women are still objects socially constructed to fit within a certain hierarchical and patriarchal order.

What has changed is the role of the state. The shift in the constellation of forces as a result of Reformasi and democratisation that meant the state no longer monopolises public life also means the social construction of womanhood is no longer completely state-dominated. Now it is open to a range of interpretations. As a result, the dominant social construction has become a predominantly Islamic one – or at any rate, the version of Islam that conservatives would like us to believe requires subordinate, compliant women.

The irony of democratisation

In some instances, democracy has actually made things more difficult for the majority of women. I’m not talking here about ‘the bold and the beautiful’, that is, the moneyed and those with political power or backing. I am referring to vulnerable women like Lilis from Tangerang, who in 2006 became a victim of the controversial regional regulation targeting prostitution. Two months pregnant at the time, Lilis had finished work at a restaurant, and was waiting to catch public transport when she was picked up at 8pm by local public order police (petugas Tantrib). She was summarily accused of being a prostitute because she was wearing ‘sexy’ clothes – although she was, in fact, wearing long loose trousers, a shirt and a jacket. She was subsequently tried, found guilty, imprisoned and fined.

Eventually Lilis was released. But the stress she suffered caused her to start bleeding, and she lost her baby. She attempted to sue the local government for falsely arresting and prosecuting her, but failed. Then she lost her job, as did her husband, Kastoyo, a schoolteacher. They also had to move house several times, because neighbours didn’t want a ‘prostitute’ living in their midst. Eventually, the social repercussions and the ongoing trauma caused by her persecution proved too much. She died in 2008, leaving behind her husband and her only son.

Mala (Keumalawati) from Aceh is another example. She was taken in by Aceh’s ‘Syariah Police’, the Wilayutul Hisbah, because they said she was not suitably attired. In fact, Mala, who worked for a women’s NGO that supports female heads of households, was dressed according to local Islamic standards but was accompanied by her sister who was, indeed, wearing tight trousers. Women caught in such garb in Aceh often have their trousers or skirt cut with scissors in the middle of the street, are given a new skirt to wear, and are obliged to sign a statement confessing their ‘guilt’. They are forced to suffer the humiliation of being arrested, charged, summarily tried and punished in public. Mala was conservatively dressed, but was punished just for being in the company of someone who was not.

How did pornography become part of the agenda?

The proliferation of these kinds of discriminatory and bullying religiously-inspired regional laws and law enforcement institutions is largely a result of the sweeping decentralisation that followed Suharto’s fall in 1998, and the removing of restrictions on Islamic political activity. It peaked with the passing of the Anti-Pornography Law in 2008, a sort of national version of these repressive local laws.

Often what becomes a social or political issue depends on who takes the first step to define it as one. Whoever defines the issue usually gains great control over how it is publicly understood and this can often translate into political power. This was the case with pornography in Indonesia. It was socially conservative Muslims – particularly hard-line Islamists – who first publicly raised the dangers and destructive nature of pornography, claiming it threatened the moral fibre of society and the integrity of the nation. After decades of agitating, they have become more adroit at identifying issues and running socio-political campaigns than more liberal, pro-democracy groups (including women’s groups), many of which have only been on the public stage since 1998. This meant the conservatives were able early on to assert their own understandings of what constitutes pornography. They thus won control of the very definition of the term itself, obtaining a huge – and ultimately decisive – advantage in the battle over whether the anti-pornography bill would be passed.

Pornography, in the conventional sense of the word, is a more or less inevitable product of the free market, of Indonesia’s engagement in the global economy. It has long been present in Indonesia, but that is not what the Anti-Pornography Law is really about. Rather, it is a regressive attempt to create a social construction of womanhood aimed not just at containing and controlling women, but also at creating a society in line with a particular vision of what an Islamic society should be – one very different indeed to Islamic society in Indonesia today. The hard-liners on the Muslim right apparently believe that changing the law will change behaviour, despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary presented by Indonesian history and the very obvious shortcomings of the national law enforcement system.

The modus operandi of the Anti-Pornography Law thus smacks very much of New Order ways, when state ideology on womanhood was a means to buttress state ideology and power, as well as the systematic repression of civil society. The New Order believed firmly in social engineering by law and the Islamists seem to have inherited this approach, despite their long opposition to the New Order itself. But whereas the New Order’s social construction of womanhood had at least some utilitarian value, related to the regime’s developmentalist framework, the Islamist social construction of womanhood is more repressive and insidious. It is also often part of a wider agenda promoting syariah-isation by stealth.

An Islamist state ibuism?

As the cases of Lilis and Mala show, there is a trend of legal Islamisation, which has given rise to a new set of social constructions that are equally, if not more, oppressive than the old ones that prevailed under the New Order. And, more concerning still, like the New Order construction of women, the conservative Islamic one still depends on state approval and collusion – and it gets it too, as result of the Yudhoyono government’s unwillingness to oppose the hardliners.

The new Islamic construction of women is thus still a form of ‘state ibuism’, albeit with a headscarf in place of (or with!) a uniform. That is why I believe this work of mine from more than two decades ago still has something important to say about (and to!) women in Indonesian today.

Julia Suryakusuma (www.juliasuryakusuma.com) is the author of State Ibuism/Ibuisme Negara, Komunitas Bambu, Jakarta, 2011.