Luky Djani

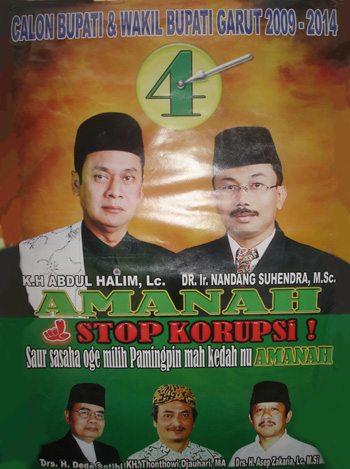

Campaign poster for local Garut elections in 2009Luky Djani |

In early January 2012, former DPR member Sofyan Usman of the United Development Party (PPP) told the anti-corruption special court that he did not deserve to be punished, even though he was clearly guilty of receiving travellers’ cheques as bribes. While reading his statement, he urged the court to dismiss the charges against him because all the money he obtained from the Batam Industrial Development Authority (approximately Rp. 1 billion or $A 110,000) had been spent on building a mosque for the local community. This argument was unsuccessful, and the anti-corruption special court sentenced the politician to 14 months imprisonment.

This is just one of an increasing number of examples where religious justifications have been invoked in corruption cases. Defendants are also increasingly making use of religious symbols like clothing and language in the hope that their overt display of religiosity will protect them from public criticism. Take the case of Yulianis, the deputy finance director of PT. Permai Group, a holding company owned by former Democrat Party treasurer Nazaruddin. Yulianis was taken in to custody after the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) caught the firm’s marketing director trying to bribe Wafid Muharam, the secretary of the Ministry of Youth and Sports. During her trial, she appeared in the anti-corruption court wearing a long, black dress and a veil that covered her face, in a style more typically associated with Muslims in the Middle East than in Indonesia. Other defendants in several other corruption trials have also appeared in the court in conservative Islamic garb very different to the clothes they normally wear.

While the involvement of religious leaders in campaigns against corruption is far from universal, in Garut, the head of the Council of Islamic Clerics and other key Muslim figures have strongly, and publicly, supported such convictions for corruption. In doing so, they are building on a long relationship between Islam and the anti-corruption movement in Indonesia, which began in the early 2000s, when Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadyah collaborated to develop a handbook containing Qur’anic verses and hadith condemning corruption in Islam’s own words.

The utilisation of religious values and symbols on both sides of the argument shows that religion is open to interpretation and manipulation, particularly in the realm of corruption. While some use it to condemn corruption, others use it to defend themselves against prosecution, or at least hope that it will promote leniency in their case rulings and sentencing.

Religion in the courtroom

In October 2008, Achmad Muttaqien, a former district secretary was standing in one of several corruption cases involving Garut’s top executives in the district’s criminal court. While the prosecution hammered the defendant with list of questions, two women prayed quietly in back of the court. One, dressed very glamorously, was the wife of the defendant. She and her companion were praying that God give the defendant strength to answer the court’s questions and he be absolved of the charges. Despite his wife’s devoted support, on 13 February 2009 Achmad Muttaqien was sentenced to five years imprisonment and fined Rp. 200 million for misusing funds to the tune of Rp. 4.5 billion from the Garut district budget.

The intriguing thing about this case was not that the former district secretary was convicted but rather why the defendant’s wife chose to pray for his acquittal in the courtroom, in such a public manner, rather than accepting his punishment (which clearly contravened Islamic teachings on honesty). She would have been better off praying a long time ago, asking God not to tempt her husband to steal from the public budget in the first place.

Clerics stand against corruption

In mid 2007, the same district fell under the media spotlight when Agus Supriyadi, then the district head, was ousted after two solid months of mass demonstrations. Not only had he lost the support of the district legislative assembly, but he was subsequently prosecuted and imprisoned by KPK on charges of embezzlement and misuse of the local budget (APBD).

One of the most critical elements in the mass movement against Supriyadi was the Council of Islamic Clerics and a number of Islamic boarding schools and universities. Garut is known as a centre for Islamic teaching in West Java. As a crossroad between Bandung, the provincial capital, and Cirebon, a centre of Islamic teaching since the period of Sunan Gunung Djati, Garut has long been exposed to new ideas, including the spread of Islam.

In the midst of national revolution, the district became the stronghold of radical Islamic movement, Darul Islam. In 1948, it was in this district that the head of the Darul Islam movement, Kartosuwiryo, declared all true Muslims should prepare themselves for holy war to establish the Islamic State of Indonesia. A number of Islamic boarding schools (pesantren) were also established in Garut around this time. One of the leading pesantren and modern Islamic education institutions is Musaddadyah, now headed by KH Cecep Abdulhalim, who played a central role during the impeachment movement against the district head.

In many ways, KH Cecep Abdulhalim – a local cleric who became heavily involved in anti-corruption campaigns after the house of a local anti-corruption NGO activist was burned down – personifies the Islamic face of the movement against corruption. In his role as chair of Council of Islamic Clerics’ Garut chapter, Abdulhalim publicly urged the authorities to take up the case, advocating that the perpetrators of the arson attack should be severely punished. In a media interview, Abdulhalim said it was every Muslim’s responsibility to defend the good against the bad. He also personally approached several Islamic organisations to join the movement, mobilising his own students and frequently appeared in front of crowds of demonstrators at anti-corruption rallies. Through his actions, he gave the anti-corruption movement legitimacy in the local community, creating solidarity among civil society organisations and the public.

Mixed messages

As events in Garut show, Islam is being used in different and somewhat contradictory ways in Indonesia’s epic struggle over corruption. On the one hand, people from all kinds of backgrounds are resorting to the use of religious symbols in a last-ditch attempt to save themselves from a harsh sentence by appearing pious in the hope that they will attract public sympathy and that the judge will show them leniency. On the other hand, Islamic figures and organisations are playing an increasingly important role in the fight against corruption in the district.

Both sides are trying to justify their actions, or defending their misbehaviour, through the use of Islamic values and symbols. These mixed messages illustrate that competing uses of religion can be interpreted as a conflict of interest. In short, the struggle against corruption – and ‘defending’ corrupt behaviour – is at the same time a symbolic struggle over values themselves.

Luky Djani (lukydd@yahoo.com) is the deputy secretary general Transparency International-Indonesia.